The Competitiveness of Nations in a Global Knowledge-Based Economy

Robin Cowan (a), Paul A.

David (b) & Dominique Foray (c)

The Explicit Economics of Knowledge: Codifcation and Tacitness

|

Content |

|

|

Abstract

1. Introduction: What’s All this Fuss over Tacit

Knowledge About?

2. How the Tacit Dimension Found a Wonderful New

Career in Economics

2.1 The Roots in the Sociology of Scientific

Knowledge, and Cognitive Science

2.2 From Evolutionary Economics to Management Strategy

and Technology Policy 3. Codification and Tacitness Reconsidered 4. A Proposed Topography for Knowledge Activities 5. Boundaries in the Re-mapped Knowledge Space and

Their Significance 6. On the Value of This Re-mapping 6.1 On the Topography Itself 6.2 On Interactions with External Phenomena |

7. The Economic Determinants of Codification 7.1 The Endogeneity of the Tacitness - Codification

Boundary 7.2 Costs, Benefits and the Knowledge Environment 7.3 Costs and Benefits in a Stable Context 7.4 Costs and Benefits in the Context of Change 8. Conclusions and the Direction of Further Work Acknowledgements References HHC: Index added

Industrial and Corporate Change, 9 (2), 2000 , 211-253 |

page 3

5.

Boundaries in the Re-mapped Knowledge Space and Their Significance

Across the space described by the foregoing taxonomic

structure it is possible to define (at least) three interesting boundaries. The ‘Collins-Latour-Callon’ boundary would

separate articulated codified knowledge from all the rest - assigning

observational situations in which there was a displaced codebook to the same

realm as that in which learning and transmission of scientific knowledge, and praxis,

were proceeding in the absence of codification. The line labeled ‘the Merton-Kuhn boundary’

puts codified and codebook-displaced situations together on its left side, and

would focus primary attention there - as it constituted the distinctive regions

occupied by modern science. That would

leave all the rest to general psychological and sociological inquiries about

‘enculturation processes’ involved in human knowledge acquisition.

Our branching structure recognizes that it is possible,

nonetheless, for epistemic communities to exist and function in the zone

to the right of the Merton-Kuhn boundary. Such communities, which may be small working

groups, comprise knowledge-creating agents who are engaged on a mutually

recognized subset of questions, and who (at the very least) accept some

commonly understood procedural authority as essential to the success of their

collective activities. The line labeled

the ‘functional epistemic community boundary’ separates them from the region

immediately to their right in the topography. Beyond that border lies the zone populated by

personal (and organizational) gurus of one shape or another, including the ‘new

age’ cult

234

leaders in whom

procedural and personal authority over the conduct of group affairs are fused.

As

is clear from the foregoing discussion, there are two quite distinct aspects of

knowledge that are pertinent in the codified-tacit discussions, although they

are often left unidentified. On the one

hand, knowledge might or might not be presented or stored in a text. This is the notion associated with

codification. On the other hand, there

is the degree to which knowledge appears explicitly in standard activities. Here, we can think of knowledge as being manifest

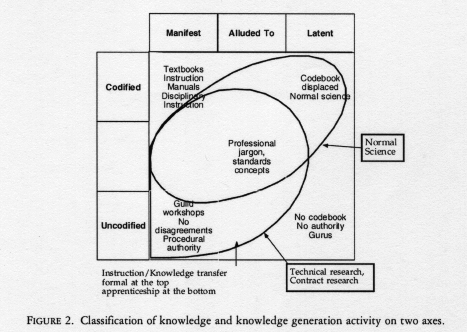

or not. Figure 2 elaborates these

two properties in a tableau. For this

purpose we have used a 3 X 3 matrix, in which one axis represents the extent of

codification: codified, partially codified, and uncodified; the other axis

represents the extent to which the knowledge is manifest, or commonly referred

to in knowledge endeavors: manifest, alluded to, and latent. These divisions that are indicated along the

vertical and horizontal axes are patently arbitrary, for mixtures in the

ordinary human knowledge activities form a continuum, rather than a set of

discrete boxes.

To

make clearer the meaning of Figure 2, it may be useful to look specifically at

the four extreme cases: the corners north-west, south-west, north-east and

south-east. Both the codified-manifest

case (the north-west corner) and the uncodified-latent case (the south-east

corner) describe situations which are easily comprehensible because the

criteria fit together

To

make clearer the meaning of Figure 2, it may be useful to look specifically at

the four extreme cases: the corners north-west, south-west, north-east and

south-east. Both the codified-manifest

case (the north-west corner) and the uncodified-latent case (the south-east

corner) describe situations which are easily comprehensible because the

criteria fit together

235

naturally.

The codified-latent case (the north-east)

was described as a situation in which the codebook is displaced while knowledge

is not tacit. Finally the uncodified-manifest

case (south-west) describes situations in which agents start to make their

discoveries, inventions and new ideas manifest (in order to diffuse them) but

still cannot use a full and stabilized codebook to do so; and even ‘writing’ a

book with which to make this new knowledge manifest does not necessarily imply

codification. It is possible that the

vocabulary or symbolic representation employed is highly idiosyncratic, that

there are many ambiguities, and so on. This

implies that while certain aspects of codification may be present (in knowledge

storage and recall, for example), other important aspects (such as an agreed

vocabulary of expression) can be missing.

The overly sharp coordinates nevertheless give us a tableau

which can be used heuristically in distinguishing major regions of the

states-space within which knowledge-groups can be working at a given moments in

their history. Instruction or deliberate

knowledge transfer is thus roughly situated in the tableau’s ‘manifest’ column,

spilling over somewhat into the ‘alluded to’ column. Formal instruction comes near the top

(‘codified’), whereas apprenticeship lies near the bottom (‘uncodified’) of the

array. The world of normal science

inquiries extends across the ellipse-shaped region that is oriented along the

minor diagonal (southwest-northeast axis) of the array, leaving out the

north-west and south-west corners. In

the former of the two excluded regions codified knowledge is most plainly

manifested for purposes of didactic instruction, in which reference is made to

textbooks, grammars and dictionaries, manuals, reference standards, and the

like. In contrast, most craft

apprenticeship training, and even some computer-based tutorial programs, occupy

the lower portion of the ‘soft-trapezoidal’ region covering the left side of

the array in Figure 2: a mixture of both codified and uncodified procedural

routines are made manifest, through the use of manuals as well as practical

demonstrations, whereas other bodies of codified knowledge may simply be

alluded to in the course of instruction. [20]

The boundaries of the world of engineering and applied

R&D also extend upwards from the south-west corner in which closed,

proprietary research

20. A number of

interesting examples are presented in Balconi’s (1998) study of worker training

programs in the modern steel-making industry, showing that what formerly could

justifiably be described as ‘rules of the art’ have been transformed into

codified knowledge of a generic sort, as well as explicit operating procedures

for the plant in question. According to

Balconi (pp. 73-74), an overly sharp distinction has been drawn by Bell and

Pavitt (1993) when they contrast the nature of the ‘learning within firms’ that

is necessary to augment the content of the formal education and training

conducted by institutions outside industry. In the cases she discusses, ‘the aim of

training [provided within the industry] is to transmit know-how by teaching

know-why (the explanations of the causes of the physical transformations

carried out [in the plant]), and know-what (codified operation practices)’.

236

groups

function on the basis of the uncodified skills (experience-based expertise) of

the team members, and their shared and manifest references to procedures that

previously were found to be successful. But,

if we are to accept the descriptions provided for us by articulate academic

engineers, those boundaries are more tightly drawn than the ones within which

science-groups operate; in particular they do not reach as far upwards into the

area where there is a large body of latent but nevertheless highly codified

knowledge under-girding research and discovery (see, e.g., Vincenti, 1990;

Ferguson, 1992).

6.

On the Value of This Re-mapping

What value can be claimed for the topography of knowledge

activities that we have just presented? Evidently

it serves to increase the precision and to allow greater nuance in the

distinctions made among types of knowledge-getting and transferring pursuits. But, in addition, and of greater usefulness

for purposes of economic analysis, it will be seen to permit a more fruitful

examination of the influence of external, economic conditions upon the codification

and manifestation of knowledge as information. A number of the specific benefits derived from

looking at the world in this way warrant closer examination, and to these we

now turn.

Figures 1 and 2 clean up a confusion concerning the putative

tacitness of the working knowledge of scientists in situations that we have

here been able to characterize by applying the ‘displaced codebook’ rubric. A number of studies, including some widely cited

in the literature, seem to have placed undue reliance upon an overly casual

observational test, identifying situations where no codebook was manifestly

present as instances showing the crucial role of ‘tacit knowledge’, pure and

simple (see e.g. Collins, 1974; Latour and Woolgar, 1979; Latour, 1987;

Traweek, 1988). It now should be seen

that this fails to allow for the possibility that explicit references to

codified sources of ‘authority’ may be supplanted by the formation of ‘common

knowledge’ regarding the subscription of the epistemic community to that

displaced but nonetheless ‘authoritative’ body of information.

The location of the Collins-Latour-Callon boundary in Figure

1, and its relationship to the regeneration of knowledge in tacit form,

signifies that this latter process - involving the mental ‘repackaging’ of

formal algorithms and other codified materials for more efficient retrieval and

frequent applications,

237

including

those involved in the recombinant creation of new knowledge - rests upon the

pre-existing establishment of a well-articulated body of codified, disciplinary

tools. [21]

Economists’ recent concerns with the economics of knowledge

tend to lie in the ‘no disagreements’ (uncodified, manifest) box in Figure 2. We are talking here about the literature that

views reliance upon ‘sticky data’ or ‘local jargons’ as methods of

appropriating returns from knowledge. This

is the region of the map in which knowledge-building gives rise to the ‘quasi’

aspect of the description of knowledge assets as quasi-public goods. The immediate implication is that to determine

the degree to which some particular pieces of knowledge are indeed only

quasi-public goods calls for a contextual examination of both the completeness

of the codification and the extent of manifestation.

The argument has recently been advanced, by Gibbons et

al. (1996), that an emergent late twentieth century trend was the rise of a

new regime of knowledge production, so-called Mode 2. This has been contrasted with the antecedent

dominant organizational features of scientific inquiry, associated with Mode 1:

in particular, the new regime is described as being more reliant upon tacit

knowledge, and transdisciplinary - as opposed to the importance accorded by

Mode 1 to the publication of codified material in areas of disciplinary

specialization as the legitimate basis of collegiate reputational status,

selection decisions in personnel recruitment, and the structuring of criteria

for evaluating and rewarding professional performance. Doubts have been raised about the alleged

novelty and self-sufficiency of Mode 2 as a successor that will displace the

antecedent, highly institutionalized system of research and innovation (see

e.g. David et al, 1999, and references therein). But the main point to be noted in the present

context is that such coherence and functionality as groups working in Mode 2

have been able to obtain would appear to rest upon their development of

procedural authority to which the fluid membership subscribes.

6.2 On

Interactions with External Phenomena

How do changes in information and communications technologies

impinge

21. Further, in much the

same vein, it is quite possible that practiced experimental researchers, having

developed and codified procedures involving a sequence of discrete steps, may

be observed discussing and executing the routine in a holistic manner - even to

the point of finding it difficult to immediately articulate every discrete

constituent step of the process. The

latter is a situation found quite commonly when experienced computer

programmers are asked to explain and document the strings of code that they

have just typed. The phenomenon would

seem to have more to do with the efficient ‘granularity’ for mental storage

and recall of knowledge, than with the nature of the knowledge itself, or

the manner in which it was initially acquired.

238

upon

the distribution of knowledge production and distribution activities within the

re-mapped space described by our topography? The first and most obvious thing to notice is

the endogeneity of the boundaries (which we discuss more fully in the next

section). In the new taxonomy there are

two interesting distinctions: knowledge activities may use and produce codified

or uncodified knowledge, or they may use and produce knowledge that is either

manifest or latent. We should re-state

here that ‘boundary’ is not being used in reference to the distribution of the

world knowledge stock, but instead to the prevailing locus of the activities of

knowledge agents in a specific cognitive, temporal and social milieu. Nevertheless, it is most likely to be true

that the situation of a group’s knowledge stock will be intimately related to,

and possibly even coterminous with, the location of its knowledge production

activities.

Organizational goals affect the manifest-latent boundary. Activities that couple teaching with research,

for example, will be pushed towards the more fully ‘manifest’ region of the

state space. This consideration will be important

in studies of the economics of science, and of the institutional organization

of academic research activities more generally. [22]

The positioning of the endogenously determined boundary

separating the codified from the uncodified states of knowledge activities will

be governed by the following three sets of forces, which we examine at greater

length below. For the present it is

sufficient simply to note that these include: (i) costs and benefits of the

activity of codification; (ii) the costs and benefits of the use of the

codified knowledge (data compression, transmission, storage, retrieval,

management, etc.); and (iii) feedbacks that arise because of the way codified

knowledge is used to generate further codified knowledge.

A given discipline’s age (or the stage of development

reached in the life cycle of a particular area of specialization) affects both

of the boundaries. The evolution of a

discipline, a technological domain (or of a research group or a community of

practitioners) may now be described as a movement in the two-dimensional plane

of the tableau in Figure 2. Let us

illustrate this by taking a lead from Kuhn (1962) and begin, early in the life

cycle of a research program, with activities centered in the south-east corner

of the array: a disparate collection of individual researchers and small teams,

working without any commonly accepted procedural authority, generating

knowledge that remains highly idiosyncratic and uncodified, and having only a

very restricted scope for transmission of its findings beyond the confines of

the immediate work-group(s). Subsequently,

if and when these investigations

22. A recent

exemplification of the application of the approach formalized here is available

in Geuna’s (1999) studies of the economics of university funding for research

in science and engineering, and how different funding structures affect the

types of activity within the modern European university system.

239

have

begun bearing fruit, work in the field coalesces around a more compact set of

questions and the locus of its knowledge activities shifts westward, as agents

make their discoveries and inventions manifest either in physical artifacts,

conference presentations and published papers. This is where the codification process begins.

But even though scholarly texts may be

produced, because the concepts involved and language in which these reports are

couched have not yet been thoroughly standardized, codification must still be

considered very incomplete. Thenceforward,

the emerging discipline’s course follows a northerly track, spreading towards

the north-east as disputes arise from inconsistencies in description and

interpretation, and conflicts emerge over the specifics of the way the language

is to be standardized. As these debates

are resolved and closure on a widening range of issues is achieved, the

characteristic activities migrate eastward in the space of Figure 2, landing up

in the region where most of the actual research activity is carried on within

the ‘latent-codified’ and ‘manifest-partially codified’ domains that typify

normal science.