The Competitiveness of Nations in a Global Knowledge-Based Economy

Robin Cowan (a), Paul A.

David (b) & Dominique Foray (c)

The Explicit Economics of Knowledge: Codifcation and Tacitness

|

Content |

|

|

Abstract

1. Introduction: What’s All this Fuss over Tacit

Knowledge About?

2. How the Tacit Dimension Found a Wonderful New

Career in Economics

2.1 The Roots in the Sociology of Scientific

Knowledge, and Cognitive Science

2.2 From Evolutionary Economics to Management Strategy

and Technology Policy 3. Codification and Tacitness Reconsidered 4. A Proposed Topography for Knowledge Activities 5. Boundaries in the Re-mapped Knowledge Space and

Their Significance 6. On the Value of This Re-mapping 6.1 On the Topography Itself 6.2 On Interactions with External Phenomena |

7. The Economic Determinants of Codification 7.1 The Endogeneity of the Tacitness - Codification

Boundary 7.2 Costs, Benefits and the Knowledge Environment 7.3 Costs and Benefits in a Stable Context 7.4 Costs and Benefits in the Context of Change 8. Conclusions and the Direction of Further Work Acknowledgements References HHC: Index added

Industrial and Corporate Change, 9 (2), 2000 , 211-253 |

page 2

3.

Codification and Tacitness Reconsidered

It will be easiest for us to start not with concept of tacit

knowledge but at the opposite and seemingly less problematic end of the field,

so to speak, by

12. See, for example,

Kealey (1996) on industrial secrecy as the suitable ‘remedy’ for the problem of

informational spillovers from research, and the critique of that position in

David (1997).

224

asking

what is to be understood by the term ‘codified knowledge’. Its obvious reference is to codes, or

to standards - whether of notation or of rules, either of which may be promulgated

by authority or may acquire ‘authority’ through frequency of usage and common

consent, i.e. by defacto acceptance.

Knowledge that is recorded in some codebook serves inter

alia as a storage depository, as a reference point and possibly as an

authority. But information written in a

code can only perform those functions when people are able to interpret the

code; and, in the case of the latter two functions, to give it more or less

mutually consistent interpretations. Successfully reading the code in this last

sense may involve prior acquisition of considerable specialized knowledge

(quite possibly including knowledge not written down anywhere). As a rule, there is no reason to presuppose

that all people in the world possess the knowledge needed to interpret the

codes properly. This means that what is

codified for one person or group may be tacit for another and an utterly

impenetrable mystery for a third. Thus

context - temporal, spatial, cultural and social - becomes an important

consideration in any discussion of codified knowledge.

In what follows, we make extensive use of the notion of a

codebook. We use ‘codebook’ both to

refer to what might be considered a dictionary that agents use to understand

written documents and to apply it also to cover the documents themselves. This implies several things regarding

codification and codebooks. First,

codifying a piece of knowledge adds content to the code-book. Second, codifying a piece of knowledge draws

upon the pre-existing contents of the codebook. This creates a self-referential situation,

which can be particularly severe when the knowledge activity takes place in a

new sphere or discipline. Initially,

there is no codebook, either in the sense of a book of documents or in the

sense of a dictionary. Thus initial

codification activity involves creating the specialized dictionary. Models must be developed, as must the

vocabulary with which to express those models. When models and a language have been

developed, documents can be written. Clearly,

early in the life of a discipline or technology, standardization of the

language (and of the models) will be an important part of the collective

activity of codification. When this ‘dictionary’

aspect of the codebook becomes large enough to stabilize the ‘language’, the

‘document’ aspect can grow rapidly [for a further discussion of this issue see

Cowan and Foray (1997)]. But new

documents will inevitably introduce new concepts, notation and terminology, so

that ‘stabilization’ must not be interpreted to imply a complete cessation of

dictionary-building.

The meaning of ‘codification’ intersects with the recent

literature on economic growth. Much of

modern endogenous growth theory rests on

225

the

notion that there exists a ‘world stock of knowledge’ and, perhaps, also a

‘national knowledge-base’ that has stock-like characteristics. This is true particularly of those models in

which R&D is seen as both drawing upon and adding to ‘a knowledge stock’

which enters as an input into production processes for other goods. How ought we to characterize this, or indeed

any related conceptualization of a world stock of knowledge? Implicit in this literature is that this

stock is codified, since part or all of it is assumed to be freely accessible

by all economic agents in the system under analysis. Unpacking this idea only partially suffices to

reveal some serious logical difficulties with any attempt to objectify ‘a

social stock of knowledge’, let alone with the way that the new growth theory

has sought to employ the concept of an aggregate knowledge stock. [13]

The ‘new growth theory’ literature falls squarely within the

tradition emphasizing the public-goods nature of knowledge. So, one may surmise that the world stock of

knowledge surely has to be the union of private stocks of codified knowledge:

anything codified for someone is thereby part of the world knowledge stock. Such reasoning, however, may involve a fallacy

of composition or of aggregation. One

might reasonably have thought that the phrase ‘world knowledge stock’ refers to

the stock available to the entire world. But if the contextual aspect of knowledge and

codification (on which, see supra) is to be taken seriously, the world

stock of codified knowledge might better be defined as the intersection of

individuals’ sets of codified knowledge - that being the portion that is

‘shared’ in the sense of being both known and commonly accessible. It then follows that the world stock of

knowledge, being the intersection of private stocks, whether codified or tacit,

is going to be very small. [14]

The foregoing suggests that there is a problem in principle

with those models in the ‘new growth theory’ which have been constructed around

(the formalized representation of) a universal stock of technological knowledge

to which all agents might contribute and from which all agents can draw

costlessly. That, however, is hardly the

end of the difficulties arising from the

13. See Machlup (1980,

pp. 167-169) for a discussion of ‘the phenomenological theory of knowledge’

developed by Schutz and Luckmann (1973, chs 3-4). The latter arrive at a concept described by

Machlup as: ‘the fully objectivated [sic) knowledge of society, a social

stock of knowledge which in some sense is the result of a socialization of

knowledge [through individual interactions involving private stocks of

subjective but inter-subjectively valid knowledge) and contains at the same

time more and less than the sum of the private stocks of subjective

knowledge... This most ingenious phenomenological theory of the stock of

knowledge in society is not equipped to deal with... the problem of assessing

the size of the stock and its growth.’

14. It is clear that the

availability of two operators - union and intersection - when combined with two

types of knowledge - tacit and codified - leads to a situation in which ‘the

world stock of knowledge’ is going to take some further defining.

226

primacy

accorded to the accumulation of ‘a knowledge stock’ in the recent literature on

endogenous economic growth. The

peculiarities of knowledge as an economic commodity, namely, the heterogeneous

nature of ideas and their infinite expansibility, have been cast in the

paradigm ‘new economic growth’ models as the fundamental non-convexity,

responsible for increasing returns to investment in this intangible form of

capital. Heterogeneity implies the need

for a metric in which the constituent parts can be rendered commensurable, but

given the especially problematic nature of competitive market valuations of

knowledge, the economic aggregation problem is particularly vexatious in this

case.

Furthermore, the extent to which the infinite expansibility

of knowledge actually is exploited therefore becomes a critical matter in

defining the relevant stock - even though in most formulations of new growth

theory this matter has been glossed over. Critics of these models’ relevance have quite

properly pointed out that much technologically relevant knowledge is not

codified, and therefore has substantial marginal costs of reproduction and reapplication;

they maintain that inasmuch as this so-called ‘tacit knowledge’ possesses the

properties of normal commodities, its role in the process of growth approaches

that of conventional tangible capital. [15]

If it is strictly complementary with the

codified part of the knowledge stock, then the structure of the models implies

that either R&D activity or some concomitant process must cause the two

parts of the aggregate stock to grow pari passu. Alternatively, the growth of the effective

size of the codified knowledge stock would be constrained by whatever governs

the expansion of its tacit component. Pursuing

these points further is not within the scope of this paper, however; we wish

merely to stress once again, and from a different perspective, that the nature

of knowledge, its codification or tacitness, lurks only just beneath the

surface of important ideas about modern economic growth.

Leaving to one side, then, the problematic issue of defining

and quantifying the world stocks of either codified knowledge or tacit

knowledge, we can now turn to a fundamental empirical question regarding tacit

knowledge. Below,

15. This view could be

challenged on the grounds that knowledge held secretly by individuals is not

distingushable from labor (tangible human capital) as a productivity input,

but, unlike tangible physical capital, the existence of undisclosed knowledge

assets cannot be ascertained. Machlup (1980,

p. 175), in the sole passage devoted to the significance of tacit knowledge,

adopts the latter position and argues that: ‘Generation of socially new

knowledge is another non-operational concept as long as generation is not

complemented by dissemination.... Only if [an individual) shares his knowledge

with others can one recognize that new knowledge has been created. Generation of knowledge without dissemination

is socially worthless as well as unascertainable. Although “tacit knowledge” cannot be counted

in any sort of inventory, its creation may still be a part of the production of

knowledge if the activities that generate it have a measureable cost.’

227

we

address explicitly whether some situations, described as rife with tacit

knowledge, really are so, but for the moment we can make an important point

without entering into that issue.

Some activities seem to involve knowledge that is unvoiced -

activities which clearly involve knowledge but which refer only seldomly to

texts; or, put another way, which clearly involve considerable knowledge beyond

the texts that are referred to in the normal course of the activity. [16]

Thus

we can ask why is some knowledge silent, or unvoiced? There are two possible explanations: the

knowledge is unarticulable or, being capable of articulation, it remains

unvoiced for some other reason.

Why would some knowledge remain unarticulable? The standard economist’s answer is simply that

this is equivalent to asking why there are ‘shortages’, to which one must reply

‘there are no shortages’ when there are markets. So, the economist says, knowledge is not

articulated because, relative to the state of demand, the cost and supply price

is too high. Articulation, being social

communication, presupposes some degree of codification, but if it costs too

much actually to codify, this piece of knowledge may remain partly or wholly

uncodified. Without making any

disparaging remarks about this view, we can simply point out that there is some

knowledge for which we do not even know how to begin the process of

codification, which means that the price calculation could hardly be undertaken

in the first place. Recognition of this

state of affairs generates consensus on the uncodifiable nature of the

knowledge in question. We raise this to

emphasize the important point in what follows that the category of the

unarticulable (which may be coextensive with the uncodifiable) can safely be

put to one side. That, of course,

supposes there is still a lot left to discuss.

It is worth taking note of the two distinctions we have just

drawn, and the degree to which they define coextensive sets of knowledge. Knowledge that is unarticulable is also

uncodifiable, and vice versa: if it is (not) possible to articulate a thought

so that it may be expressed in terms that another can understand, then it is

(not) possible to codify it. This is the

source of the statement above that articulation presupposes codifiability. It is not the case, though, that codifiability

necessitates codification; a paper may be thought out fully, yet need not

actually be written out. Operationally,

the codifiability of knowledge (like the articulable nature of a thought)

cannot be ascertained independently from the actions of codification and

articulation. But, when we consider the

question of the status of knowledge with reference to multiple contexts, the

preceding strictly logical relations (implied by a single, universal

16. We note that

activities involving ‘unvoiced knowledge’ are often assumed to involve thereby

tacit knowledge. We argue below that

this is too hasty.

228

context)

are not exhaustive categories. Thus we

see the possible emergence of an additional category: codified (sometime,

somewhere) but not articulated (now, here). [17]

This observation implies that care needs

to be taken in jumping from the observed absence of codified knowledge

in a specified context to the conclusion that only some non-codifiable (i.e.

tacit) knowledge is available or employed.

It is within the realm of the codifiable or

articulable-yet-uncodified that conventional price and cost considerations come

into play in an interesting way, for within that region there is room for

agents to reach decisions about the activity of codification based upon its

costs and benefits. We shall discuss the

factors entering into the determination of that knowledge-status more fully

below.

4. A Proposed

Topography for Knowledge Activities

We now proceed to examine a new knowledge topography, from

which it will soon be evident that the realm of ‘the tacit’ can be greatly

constricted, to good effect. The new

topography we propose is meant to be consulted in thinking about where various

knowledge transactions or activities take place, rather than where knowledge of

different sorts may be said to reside. We

should emphasize that as economists, and not epistemologists, we are

substantively more interested in the former than in the latter.

By knowledge activities we refer to two kinds of activities:

the generation and use of ‘intellectual (abstract) knowledge’; and the

generation and use of ‘practical knowledge’, which is mainly knowledge about

technologies, artifacts (how to use this tool or this car, or how to improve

their performances) and organizations.

Given that definition, we need to clarify the distinction

between knowledge embodied in an artifact and codified knowledge about an

artifact. The distinction between

embodied and disembodied knowledge is a nice way for economists to capture

features of intersectoral flows (of technologies), particularly in an input-output

framework. Therefore, the fact that knowledge

is embodied in a machine tool is not to be conflated with the codification problem.

Knowledge about the production and the

use of artifacts, however, falls within our set of issues about codification:

does the use of this new tool require the permanent reference to a set of

codified instructions or not? We can put

this point in a slightly different way. From

the perspective

17.

In understanding these distinctions it is important to remember that we are

discussing knowledge activities, and the kinds of knowledge used in them. Thus we can observe activities in which the

knowledge has been codified at some point in history but is not articulated in

current endeavors.

229

of

a producer, any artifact, from a hammer to a computer, embodies considerable

knowledge. The artifact often is an

exemplar of that knowledge, and can sometimes be thought of as a ‘container’ or

‘storage vessel’ for it, as well as the means through which the knowledge may

be marketed. From the point of view of

the user, however, this is not necessarily the case. While any user will admit that the producer

needed a variety of kinds of knowledge to produce the artifact, this is of

little practical interest. The knowledge

of interest to the purchaser of a hammer or a PC, whether codified or not - and

indeed that often is the issue - is how to use the artifact, rather than the

knowledge that was called upon for its design and fabrication. Of course, the latter may bear upon the

former.

Part of the reason for this interpretation of what is to be

located in our topography is simply that discussions about ‘where knowledge

resides’ are difficult to conduct without falling into, or attempting to avoid,

statements about the relative sizes of the stocks of tacit and codified

knowledge, and their growth rates. By

and large, pseudo-quantitative discussions of that sort rarely turn out to be

very useful; indeed, possibly worse than unhelpful, they can be quite

misleading. Although there is no

scarcity of casual assertions made regarding the tendency toward increasing

(relative) codification, the issue of the relative sizes of the constituent

elements of the world stocks of scientific and technological knowledge resists

formal quantitative treatment. That is

to say, we really cannot hope to derive either theoretical propositions or

empirical measures regarding whether or not the relative size of the codified

portion must be secularly increasing or decreasing, or alternatively, whether

there is a tendency to a steady state. The

fundamental obstacle is the vagueness regarding the units in which ‘knowledge’

is to be measured.

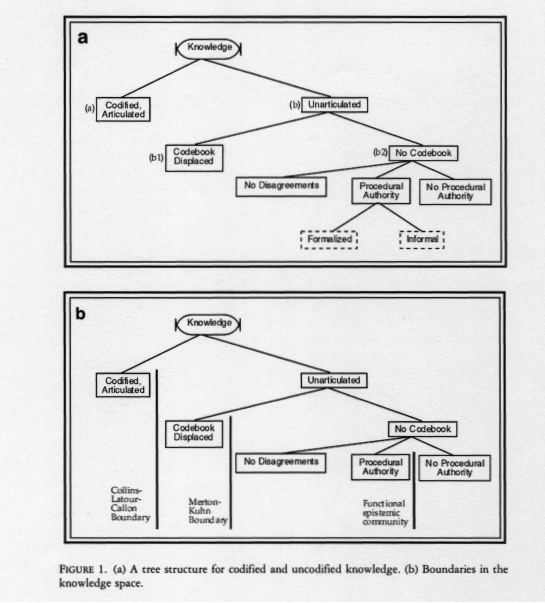

To begin, we shall consider a topological tree structure in

which distinctions are drawn at four main levels. A tripartite branching on the uppermost level

breaks the knowledge transaction terrain into three zones: articulated (and

therefore codified), unarticulated and unarticulable. Setting the third category aside as not very

interesting for the social sciences, we are left with the major

dichotomy shown in Figure 1:

(a)

Articulated (and thus codified). Here knowledge is recorded and referred

to by ‘the group’, which is to say, ‘in a socio-temporal context’. Hence we can surmise that a codebook exists,

and is referred to in the usual or standard course of knowledge-making and

-using activities.

(a)

Articulated (and thus codified). Here knowledge is recorded and referred

to by ‘the group’, which is to say, ‘in a socio-temporal context’. Hence we can surmise that a codebook exists,

and is referred to in the usual or standard course of knowledge-making and

-using activities.

(b)

Unarticulated. Here we refer to knowledge that is not invoked explicitly

in the typical course of knowledge activities. Again, the concept of a context or group is

important.

230

In

case (a) a codebook clearly exists, since this is implicit in knowledge being

or having been codified. In case (b) two

possible sub-cases can be considered. In

one, knowledge is tacit in the normal sense - it has not been recorded either

in word or artifact, so no codebook exists. In the other, knowledge may have been

recorded, so a codebook exists, but this book may not be referred to by members

of the group - or, if it is, references are so rare as to be indiscernible to

an outside observer. Thus, at the next

level, ‘unarticulated’

231

splits

into two branches: (b. 1) in the situation indicated to the left, a source or

reference manual does exist but it is out of sight, so we say the situation is

that of a displaced codebook; and (b.2) to the right lie those

circumstances in which there truly is no codebook, but in which it would be

technically possible to produce one.

(b. 1) When a codebook exists, we still may refer to the

situation in which knowledge is unarticulated because within the group context

the codebook is not manifest; it is not explicitly consulted, nor in

evidence, and an outside observer therefore would have no direct indication of

its existence. The contents of the

codebook in such situations have been so thoroughly internalized, or absorbed

by the members of the group, that it functions as an implicit source of

authority. To the outside observer, this

group appears to be using a large amount of tacit knowledge in its

normal operations. [18]

A ‘displaced codebook’ implies that a codified body of

common knowledge is present, but not manifestly so. Technical terms figure in descriptive discussion

but go undefined because their meaning is evident to all concerned; fundamental

relationships among variables are also not reiterated in conversations and

messages exchanged among members of the group or epistemic community. [19] In

short, we have just described a typical state of affairs in what Kuhn (1962)

referred to as ‘normal science’; it is one where the knowledge base from which

the researchers are working is highly codified but, paradoxically, its

existence and contents are matters left tacit among the group unless some

dispute or memory problem arises. We may

analogously describe ‘normal technology’ as the state in which knowledge about

artifacts is highly codified but the codebook is not manifest.

Identification of the zone in which knowledge is codified

but the existence of codification is not manifest is an extremely important

result. But it poses a very difficult

empirical problem (or perhaps a problem of observation). This point is crucial in understanding the

economic problem raised by the management of knowledge in various situations:

when the codebook is displaced and knowledge is highly codified, new needs for

knowledge transfer or storage (or knowledge transactions generally) can be

fulfilled at a rather low cost (the cost of making the existing codebook

manifest), whereas when there is no

18. Here we may remark

that the ability to function effectively, possibly more effectively with the

codebook out of sight (e.g. to pass closed-book exams), often is one criterion

for entry, or part of the initiation into the group. Not being truly an initiated ‘insider’ is

generally found to be a considerable impediment to fully understanding the

transactions taking place among the members of any social group, let alone for

would-be ethnographers of ‘laboratory life’.

19. This often infuriates

outsiders, who complain vociferously about excessive jargon in the writings and

speeches of physicists, sociologists, economists, psychologists and...

232

codebook

at all, the cost will be very high (the cost of producing a codebook, which

includes costs of developing the languages and the necessary models).

This suggests that it would be useful to reconsider closely

the many recent empirical studies that arrive at the conclusion that the key

explanation for the observed phenomenon is the importance of tacit knowledge. That perhaps is true, but it is quite

difficult to document convincingly; most of such studies fail to prove that

what is observed is the effect of ‘true tacitness’, rather than highly codified

knowledge without explicit reference to the codebook. By definition, a codebook that is not manifest

will be equally not observed in that context, so it is likely that simple

proxies for ‘tacitness’ (such as whether communication of knowledge takes place

verbally in face-to-face transactions rather than by exchanges of texts) will

be misleading in many instances. Differentiating

among the various possible situations certainly requires deep and careful case

studies.

(b.2) When there is

no codebook, we again have a basic two-way division, turning on the existence

or non-existence of disputes. There may

be no disagreements. Here there is

stabilized uncodified knowledge, collective memory, convention and so on. This is a very common situation with regard to

procedures and structures within organizations. The IMF, for example, has nowhere written that

there in only one prescription for all the monetary and financial ills of the

world’s developing and transition economies; but, its advisers, in dispensing

‘identikit’ loan conditions, evidently behaved as if such a ‘code’ had been

promulgated. Such uncodified-but-stable

bodies of knowledge and practice, in which the particular epistemic community’s

members silently concur, will often find use as a test for admission to the

group or a signal of group membership to outside agents.

Where there are disagreements and no codebook is available

to resolve them within the group, it is possible that there exist some rules or

principles for dispute resolution. Elsewhere,

such ‘procedural authority’ may be missing. This is the chosen terrain of individual

‘seers’, such as business management gurus like Tom Peters, and others who

supply a form of ‘personal knowledge about organizational performance’. Equivalently, in terms of the outward

characteristics of the situation, this also might describe the world of ‘new

age’ religions - in contradistinction to structured ecclesiastical

organizations that refer to sacred texts.

There is, however, another possibility, which creates a

three-fold branch from node b.2: it may be the case that when disagreements

arise there is some procedural authority to arbitrate among the contending

parties. Recall that the situation here,

by construction, is one in which the relevant knowledge is

233

not

codified, and different members of the organization/group have distinct bodies

of tacit knowledge. When these sources

of differences among their respective cognitive contexts lead to conflict about

how to advance the group’s enterprise or endeavor, the group cannot function

without some way of deciding how to proceed - whether or not this has been

explicitly described and recorded. Clearly, once such a procedure is formalized

(codified), we have a recurrence of a distinction paralleling the one drawn at

the top of the tree in Figure 1, between codified and ‘unarticulated’. But this new bifurcation occurs at a meta-level

of procedures for generating and distributing knowledge, rather than

over the contents of knowledge itself. We

can, in principle, distinguish among different types of groups by using the

latter meta-level codified-tacit boundary. So the whole taxonomic apparatus may be

unpacked once again in discussing varieties of ‘constitutional’ rules for

knowledge-building activities. But that

would carry us too far from our present purposes.