Microeconomics

Macroeconomics

SISTERetrics

SITES

Compleat World Copyright Website

World Cultural Intelligence Network

Dr. Harry Hillman Chartrand, PhD

Cultural Economist & Publisher

©

h.h.chartrand@compilerpress.ca

215 Lake Crescent

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan

Canada,

S7H 3A1

Launched 1998

|

Microeconomics 6.0 Market Failure (cont'd)

|

||||||

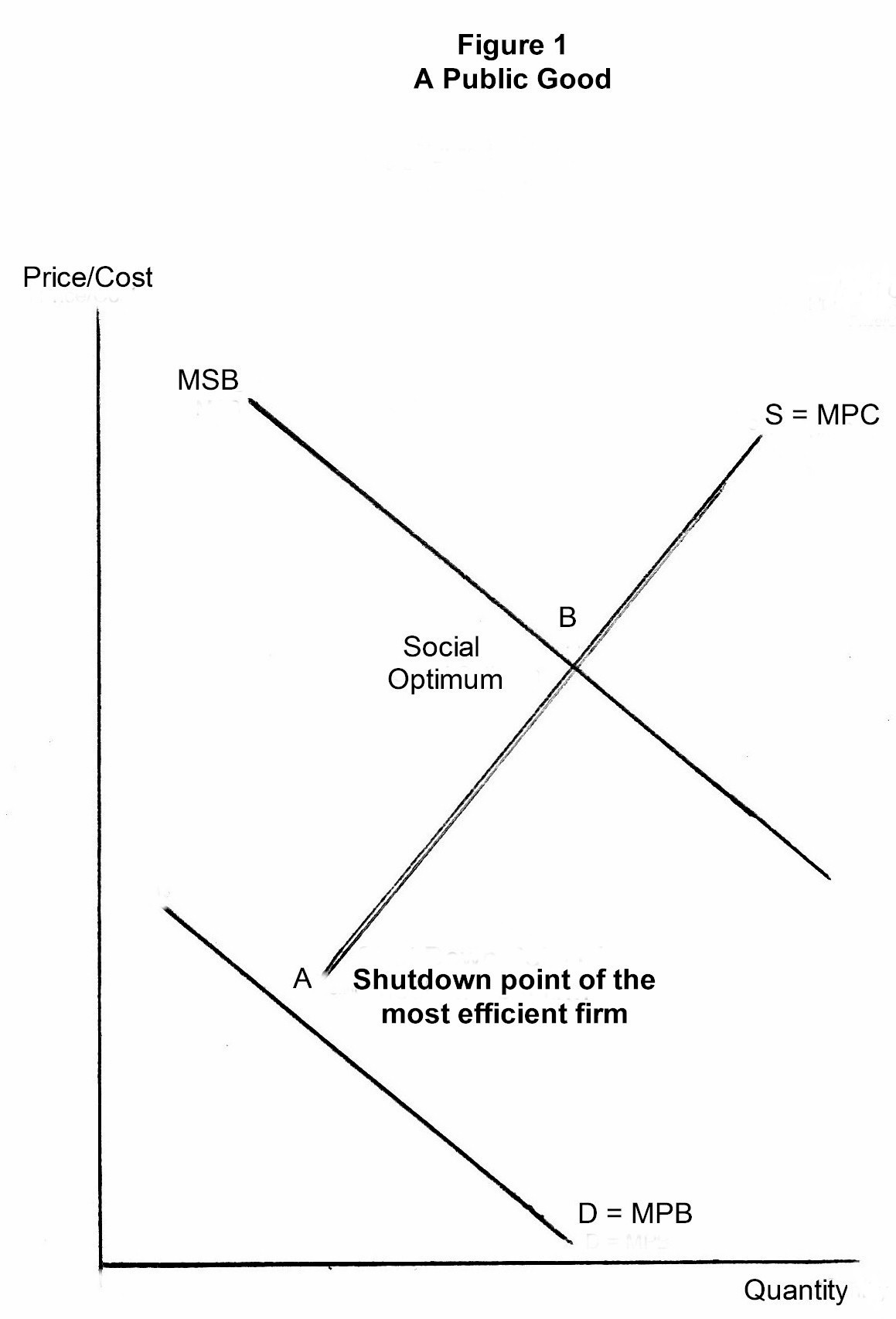

3. Public Goods

O

Reality is, however, more complicated. Thus a seemingly pure private good such as a chocolate bar can generate negative externalities when its wrapper is thrown to the ground as garbage. Some one else must pick it up and they should be paid to do so. Allowing for externalities there is thus a spectrum of goods ranging from purely private to purely public. In what follows traditional public goods such as national defense are examined and then two contemporary examples - common natural resources (CNRs) and the knowledge commons or public domain of a knowledge-based economy. i - Traditional (MKM C11/238-40; 224-25; 247-249; 228-231) Traditional public goods include such things as national defense, mass vaccination, the Census, etc., as well as public monopolies or francises, e.g., of urban roads, water and sewers. Public supply may be necessary because some public goods are 'lumpy' requiring a very large initial investment with returns spread over a very long time horizon to achieve and maintain minimum optimum scale, or because:

a) the State does

b)

The more public a good the less likely it is that private

producers will willing supply a socially optimal output and

the more likely only the State will do so. Public

provision is also necessary because some consumers will willingly pay for

some but not all public goods creating a `free rider`problem and hence compulsory taxation becomes the

necessary revenue source. The State can subsidize or substitute

for The more public a good the less likely it is that private

producers will willing supply a socially optimal output and

the more likely only the State will do so. Public

provision is also necessary because some consumers will willingly pay for

some but not all public goods creating a `free rider`problem and hence compulsory taxation becomes the

necessary revenue source. The State can subsidize or substitute

for

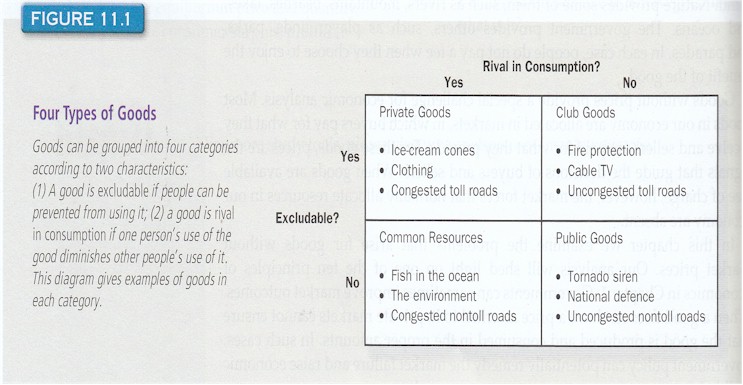

ii - Natural Commons

If the modern environmental movement was born with publication of Silent Spring by Rachel Carson in 1962 it was in 1968 that Garrett Hardin, a biologist, published “The Tragedy of the Commons” igniting the contemporary ecology movement. Hardin demonstrated that unfettered competition for natural resources within and between countries was destroying the natural commons, a.k.a., the environment or biosphere including the air, water, land and biodiversity living on this planet. Given such resources belong to everyone but to no one, i.e., they are public goods, competitive self-interest dictates getting for oneself as much as possible as quickly as possible with little or no consideration for others – past, present or future. This is “The Tragedy of the Commons”. Unfortunately, a variation also plagued Second World or communist command economies resulting in even greater environmental damage, debilitation and destruction.

I will mention four multilateral or global

agreements that vest CNR property rights in the Nation-State. It

is up to the Nation-State how such rights may be exercised.

As will be seen, some countries download or commodify them into tradable

permits so that they

can be bought and sold in a marketplace of private buyers and sellers.

For those interested, please see

Observation #10:

Common Natural Resource Treaties: the 1982

The best known of these multilateral

agreements is the

If a participating country comes in over its quota it must buy part of the quota of another Nation-State that has come in under its quota, or as noted above, invest in Third World projects. Thus CNR property rights now exist by legal alchemy that can be bought and sold in markets. Some countries, especially members of the European Union, in turn, divide up their national quota into marketable permits auctioned off to industries generating green house gases. Companies compete among themselves. If a firm exceeds its permitted output it must buy quota not used by another firm. A financial incentive is created to reduce green house gas emissions. In all three cases, Law of the Sea, Biodiversity and Climate, Nation-States have created legal property rights allowing a market driven by financial incentives to conserve CNR and, ideally, achieve a socially optimum price/quantity outcome. How successful such markets have been is the subject of much debate. It is important to note that the United States has not ratified any of the three above mentioned treaties.

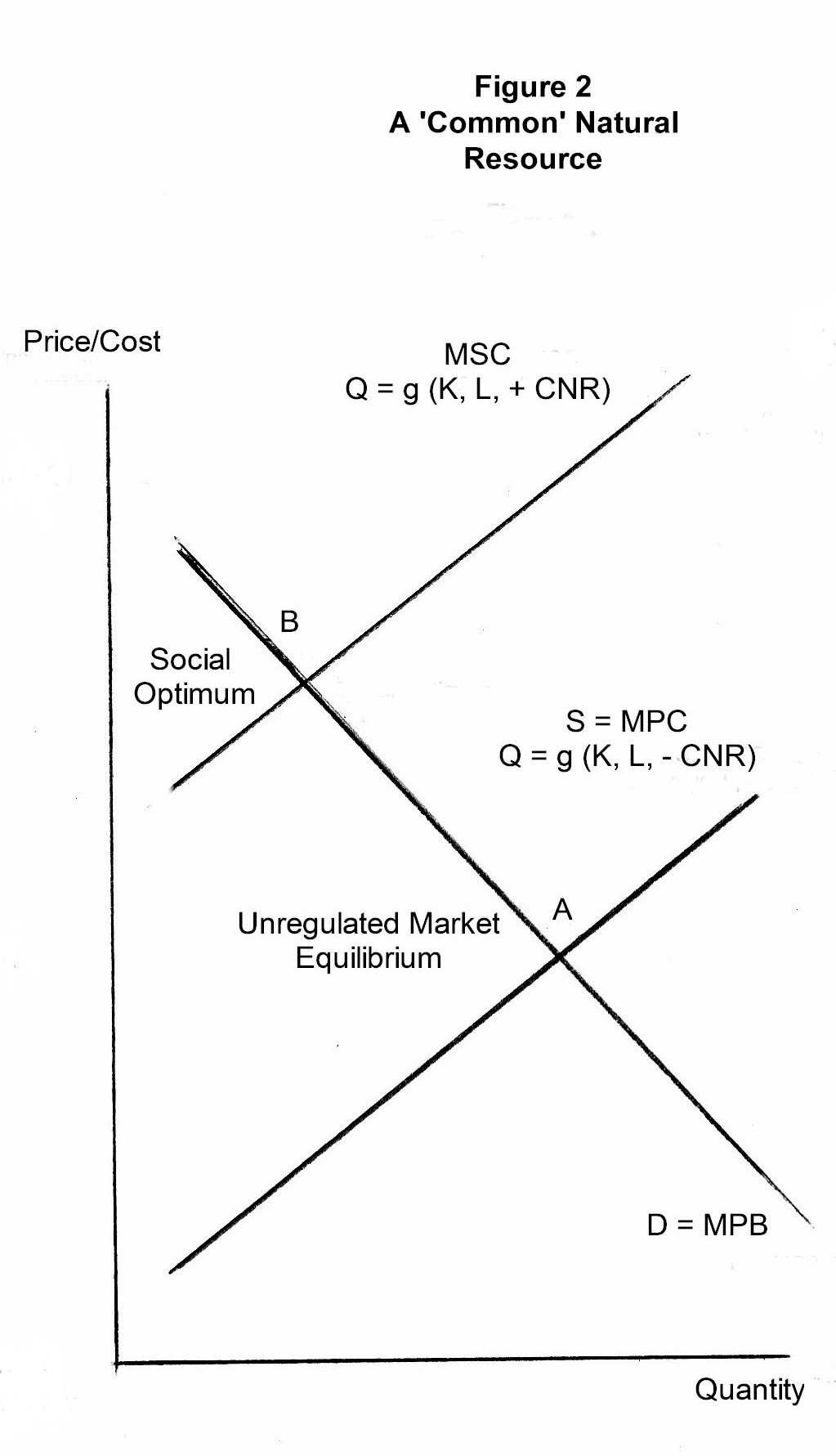

To begin, what is knowledge? To answer I offer Exhibit 1: Exhibit 1 To Know Knowledge

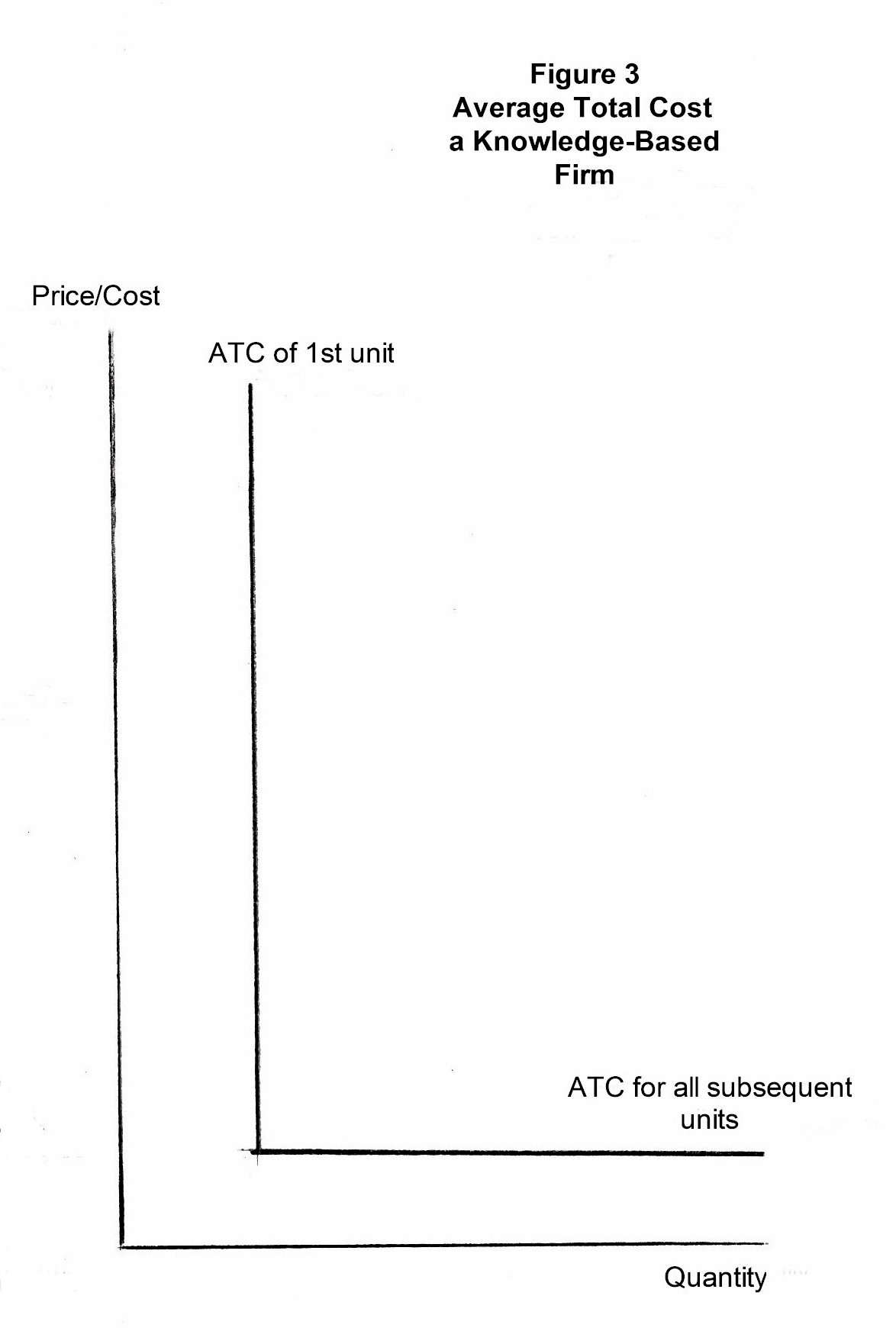

Today one hears much about the ‘knowledge-based economy’. Yet in economic theory such an economy is a contradiction in terms - an oxymoron. Knowledge is a public good, a good for which a natural market does not and cannot exist. As we have seen a private good is excludable and rivalrous in consumption. If one owns a car one has lock and key to exclude others from using it. And when one drives the car no one else can drive it, that is, driving is rivalrous. A gross example is an apple. I buy it excluding you from that particular apple and you cannot eat it after I have - rivalrous. A public good, on the other hand, is not excludable nor is it rivalrous in consumption. Consider knowledge. Once something is published, a term deriving from the Latin meaning ‘to make public’, it is hard to exclude others from learning it and if another does it does not thereby reduce the knowledge available to you. How can you have a market if the good being sold can be easily appropriated and its appropriation does not reduce one’s inventory? As will be seen below it is only through Law – contract and statutory – that a market and therefore a knowledge-based economy can exist. It is a market born of government created either through statutory intellectual property rights (IPRs) including copyright, patent, registered industrial design and trademark or through legal enforcement of confidentiality and non-disclosure clauses in contracts of employment for service or services. Put another way, without the State there can be no knowledge-based economy.

One aspect of knowledge as a

public good can be seen by e While economics is poor at prediction it is extremely good at ex poste rationalization, e.g., it cannot accurately predict the next Depression but can explain it very well after the fact. Thus intellectual property rights (IPRs) have evolved over the course of centuries (Chartrand 2011) and, as economist Paul David observed, they were not created “by any rational, consistent, social welfare-maximizing public agency” (David 1992). The resulting regime is what he calls “a Panda’s thumb”, i.e., “a striking example of evolutionary improvisation yielding an appendage that is inelegant yet serviceable” (David 1992). Paralleling development of IPRs is the evolution of multilateral and national cultural property rights (CPRs) (Chartrand 2009). In economic theory, IPRs today are justified by market failure, e.g., when market price does not reflect all benefits are received by the paying consumer and all costs of production are paid by the producers. If so there are external costs and benefits, i.e., external to market price. IPRs, in this view, are created by the State as a protection of, and incentive to, the production of new knowledge which otherwise could be used freely by others (the so-called free-rider problem). In return, the State expects creators to make new knowledge available and that a market will be created in which it can be bought and sold. But while the State wishes to encourage creativity, it does not want to foster harmful market power. Accordingly, it builds in limitations to the rights granted to creators. Such limitations embrace both Time and Space. They are also granted only with full disclosure of the new knowledge, and only for: a fixed period of time, i.e., either a specified number of years and/or the life of the creator plus a fixed number of years; and, fixation in material form, i.e., it is not ideas but rather their fixation or expression in material form (a matrix) that receives protection. Eventually, however, all intellectual property (all knowledge) enters the public domain or knowledge commons where it may be used by one and all without charge or limitation. Again, a public good first is transformed by Law into private property then transformed back through Time into a public good. Growth of the public domain and encouragement of learning are, in fact, the historical justification of the short-run monopoly granted to creators. Even while IPRs are in force, however, there are exceptions such as ‘free use’, ‘fair use’ or ‘fair dealing’ under copyright. Similarly, national statutes and international conventions permit certain types of research using patented products and processes. And, the Nation-State retains the sovereign right to waive all IPRs in “situations of national emergency or other circumstances of extreme urgency” (WTO/TRIPS 1994, Article 31b), e.g., following the anthrax terrorist attacks in 2001 the U.S. government threatened to revoke Bayer’s pharmaceutical patent on the drug Cipro (BBC News October 24, 2001). Statutory IPRs include: Copyrights - protecting the expression of an idea but not the idea itself; Patents - protecting the function of a device or process but only after disclosure of all knowledge necessary for a person normally skilled in the art to replicate the device or process; Registered Industrial Designs (design patents in the U.S.) – protecting the aesthetic or non-functional aspects of a device; and, Trademarks – protecting the name, reputation and good will of a Maker, Legal or Natural, as well as Marks of Origin such as Okanagan Made. Contractual rights to knowledge include Know-How and Trade Secrets. These take the form of non-compete, non-disclosure and/or confidentiality clauses in commercial contracts as well as contracts of employment. Unfortunately with the exception of a few new IPRs like DMRs, the IPR regime evolved before and during the Industrial Age. Arguably it served well then but not so much in the emerging post-industrial KBE. Originally intended to provide an incentive for new knowledge the current regime has, according to many observers, become an impediment stifling competition and innovation. Impediments include, among other things: patent thickets as defensive and aggressive weapons in patent wars (think Apple and Samsung); copyright and patent abuse by rights holders; and, cyber-trolling of individual consumers and producers. Some observers suggest that high tech American firms today spend more on legal defense of existing intellectual property than on research & development. Two qualifications are needed to the above description of Law as it relates to knowledge. First, rights of creators vary significantly between Anglosphere Common Law and European Civil Code traditions. Thus under the Civil Code artists/authors/creators enjoy imprescriptable moral rights, i.e., they cannot be signed away by contract. This includes employees. Such rights are viewed as human rights based on the Kantian conception that original works are extensions of their creator’s personality. Where in the Anglosphere moral rights are recognized, e.g., in Canada, they are subject to waiver if not outright assignment to a proprietor. This reflects among other things the Anglosphere legal fiction that Natural and Legal Persons enjoy the same rights. This is not the case under in Civil Code jurisdictions. Imprescriptible rights significantly enhance the bargaining power of individual creators, an important question in a knowledge-based economy characterized by increasingly contract and self-employment rather than a life long employer. Second, in the course of the current digital revolution content is being converted from analogue to digital format. By this act a new term of copyright begins for each new fixation. For those interested see my 2500 word Summary Survey of Intellectual & Cultural Property in the Global Village and Disruptive Solutions to Problems associated with the Global Knowledge-Based/Digital Economy.

4. Public Choice (MKM C22/491-509; 459-77; 487-503; 457-473) Ideally under Perfect Competition all costs and benefits are internalized in market price. Purely private goods are bought and sold with no external costs or benefits in consumption or production. Allocative efficiency is achieved the greatest good for the greatest number all at the lowest long-run average cost per unit. There is no need for intervention by Government except Equity. If, however, there is Imperfect Competition (monopoly, monopolistic competition or oligopoly) or externalities or necessary public goods there may be need for Government intervention. With imperfect competition intervention attempts to push producers towards a perfectly competitive P/Q solution. In the case of externalities, public goods, the natural and knowledge commons intervention attempts to achieve the socially optimum. Whether and how to intervene involves Public Choice. This brings us to the economics of democracy and cost/benefit analysis.

i - Economics of Democracy (MKM C22/499-503; 464-69; 493-497; 463-467) For me the seminal text in 'rational choice theory' was published in 1957 by Anthony Downs: An Economic Theory of Democracy. Other economists followed as have other disciplines including Law and Political Studies. For our purposes there are three primary actors in the public choice Each strives to maximize subject to constraint. They are: a) Voters; b) Politicians; and, c) Bureaucrats. The voter's objective function is to maximize utility inclusive of Equity, Externalities and Public Goods concerns Maximization is constrained by at least three forces:

Rational

Apathy

or

Ignorance:

If one is to be an informed voter one must learn about the issues - time

& effort. Having determined the issues one must then decide where

one stands - time & effort. Having decided one must chose the

politicians who reflects one's views - time & effort. Having

selected the candidate one must get out and vote - time & effort.

Time & effort represent costs to the voter who unless strongly motivated

is rational to be apathetic and stay ignorant of the issues and stay at

home on election day. This is one reason it is said a government is not

elected but rather defeated. Thus in federal elections only about 60%

turn out to vote; in provincial elections ~ 50%; municipal

election ~ 10%; and for school and hospital board elections only

about 1%. This has implications. Taking the federal level it means that

~30% of

the electorate can elect a majority government which can use the

'notwithstanding' clause to abrogate rights and freedoms in

the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the courts cannot intervene. The same

A

M

The objective function of politicians is to get elected or

re-elected. They are constrained primarily by Arrow's

Impossibility Theorem.

If a politician receives 51% support on every issue in an election

campaign that politician looses the election! Why? Rational

Apathy. The 51% comfortable with the politician's position tend to

stay at home in large numbers while the 49% opposed are motivated and

turn out and vote. Again t The objective function of bureaucrats is 'steady as she goes', 'no waves', 'smooth'. The bureaucracy should run like a fine tuned engine. There are two distinct types of bureaucracies - political and professional. In the U.S. all positions from the director level to Secretary of State are political appointees. Each serves at the pleasure of the sitting President. This is part of the political spoils system. It is relatively easy to appoint loyalty over competence. In parliamentary democracies like Canada there is a profession public service that fill positions from clerk up to deputy minister. Theoretically competence is valued over loyalty to the party in power. In both cases bureaucrats are constrained by politicians and voters. It is, however, of the parliamentary democracies for which I coined the Three Laws of Technocracy. Two qualifications: first, they are based on my career experience; second, the term 'technocracy' was coined by John Kenneth Galbraith to explain large corporate bureaucracies. To the degree competence is the test in both the following apply to both. The bureaucrat can relax constraints in three ways: Confuse & Conquer

A minister in government is generally

What We Don't Know Won't Hurt Us For all the talk about freedom of information the reality is the bureaucrat and the politician often practice 'What we don't know won't hurt us!' With information politicians and voters may ask questions that require the bureaucracy to answer creating waves and causing the fine tuned engine to stutter. If information is simply not collected then questions cannot be asked and therefore there is no need to answer. No waves. No stutter. Real world examples abound! When in Doubt Privatize

One aspect of parliamentary democracy is

the role of the Auditor General who is an officer not of Her Majesty,

i.e., the executive branch, but rather an officer of the House of

Commons. The office was originally established to ensure that tax

revenues authorized by the House were used

ii - Cost/Benefit Analysis The preeminent economic technique for determining the appropriateness of public intervention in the marketplace or in the production of public goods is cost-benefit analysis. Innovated by the Tennessee Valley Authority during the 1930s (part of the ‘New Deal’) cost-benefit analysis involves calculating all relevant cost and benefits of a project. In the simplest terms, if benefits outweigh costs the project goes forward; if costs outweigh benefits it does not. Benefits and costs, however, come in two flavours – those that can be quantified and generally expressed in dollars and cents and those that cannot. These can be called tangible and intangible costs and benefits. Ideally all tangible costs and benefits are quantified at market prices. Some intangibles can then be estimated in quantitative terms using techniques such as ‘willingness to pay’ surveys. Others cannot. At the end of the day, in good cost-benefit analysis, the quantitative cost/benefit ratio is calculated but then subjected to a value judgment with respect to the importance of non-quantifiable cost and benefits. In addition to tangibles and intangibles, cost-benefit analysis also recognizes first-round, second- round and subsequent effects. A market example is the impact of a frost on Florida orange juice. The first round effect is a higher price. A second round effect involves consumers shifting from more expensive orange juice to less expensive apple juice. The increase in demand for apple juice, however, causes its price to rise (second round effect) which in turn leads to a shift towards other substitutes and so on and so on. In cost-benefit analysis a decision must be made as to how many ripples should be included in the analysis. Costs and benefits also have a spatial dimension. Should only local costs and benefits be included or also regional, national and international ones? Similarly some are near term while others stretch out into the distant future. How far out in time should the analysis stretch? Furthermore, both costs and benefits are subject to increasing risk as they stretch further and further out into the future. Some risks can be subjected to probability calculation; some cannot. And some risks have a high probability but limited impact while others have a low probability but significant impact – so-called ‘Black Swan’ events. In addition costs and benefits of an intervention are distributional in nature. Some win; some lose raising questions of equity or fairness. Needless to say cost-benefit analysis is a technically demanding field involving specialized expertise. In some cases cost-benefit analysis is simply not possible. In such cases a second-best approach may be used - cost-effectiveness. As benefits and costs extend out into the future they become ever more uncertain. One calculates their current worth – their present value - using a discount rate. The higher the rate, the lower the present value of future benefits or costs. Determining the appropriate discount rate is critical to properly valuing future costs and benefits. With respect to public intervention or production of public goods there is, however, an added dimension to present value – politics. While future benefits or costs may be significant they are politically discounted to maximize election and re-election of politicians and governments. Three examples demonstrate. First, with an aging electorate politicians are more concerned with present older voters than with future generations. Quite simply future generations are not politically relevant unless the current generation says so at the ballot box. Second, there is the political ‘edifice complex’. A new $100 million bridge or building bearing a politician’s name is much more valuable politically than an annual $20,000 paint job required to preserve and maintain an existing structure for 100 years. Arguably the much reported deterioration of public infrastructure in the United States and Canada reflects this political discount rate. Third, no matter political intentions about the future the reality is we simply cannot know for certain what future generations will want, need or desire from us today. This is especially important when considering questions of sustainability. The concept of sustainability is roughly analogous to the economic concept of a 'steady state' where the existing pattern of economic activity continues through time. In the view of some economists resources are highly substitutable or fungible. Technological change will, in this view, provide a substitute for any resource that is depleted through current use. Whether or not it is appropriate to preserve a current resource for future generations thus becomes a question of substitutability. An alternative to cost/benefit analysis is the precautionary principle. Applying it means that if a new initiative has any chance of generating irreversible harm, no matter its short-term benefits, it is rejected in spite of a positive cost-benefit ratio. In fact, the precautionary principle is both an economic and moral criterion. It invokes a social responsibility to protect the public from harm even if scientific investigation finds no probable risk. In the Rio Convention mentioned above and in the European Union, the precautionary principle has been made into a statutory requirement. Its application is most apparent with respect to genetically modified foods. In the Anglosphere cost-benefit analysis has consistently found them to be a good investment. In most cases natural and genetically modified crops and animals are treated as equally safe. In the European Union, however, the remote possibility of irreversible harm to human health or the environment has led to significant restrictions on the use of genetically modified foods including labeling of all products. Dr. Thomas DeGregori argues that this 'plant protection racket' is fuelled by a Veblen Effect, named after economist Thorstein Veblen who introduced the concept of 'conspicuous consumption'. Having conducted cost/benefit analysis and determined that State intervention is appropriate there are, except to direct public investment, at least five modalities to adjust market outcomes to account for merit/demerit goods generating positive/negative externalities as well as producing public goods including appropriate management of common natural resources and the knowledge commons. These are: a) Prohibition b) Property Rights

c

d)

Regulation

e)

Subsidies;

f) Taxation. a) Prohibition b) Property Rights (MKM C10/228-30; 213-16; 257; 238) Title is the right to the possession, use, or disposal of a thing, a.k.a., Property. This implies ownership or ‘proprietorship’. In fact under Common Law & Equity there are only two classifications, Persons (legal or natural) who have rights and Property or 'things' that do not. In feudal times Title referred to a piece of land under one owner, i.e., a landed estate. Such estates were initially associated with a Title such as the Duchy of Cornwall. With Title came Property. Title was granted by the Sovereign and consisted of a bundle of rights & obligations, e.g., fealty, which were often qualified by the Sovereign. Some could be inherited; some could not; some rights were included, some were not. All Property and Persons, however, were ultimately subject to the Sovereign. Under Common Law, all Property (and, in constitutional monarchies, all Persons) remains ultimately subject to the Sovereign whether Crown or State, a.k.a., the ‘People’. Sovereignty is supreme controlling power ultimately exercised through overwhelming coercive force. The territory over which Sovereignty is asserted is established by continuing occupancy and/or by conquest. Today, Title usually takes the form of a document, deed or certificate establishing the legal right to possession. The coercive power of the State may be invoked to protect and defend it. There are three contemporary forms. There is immovable or ‘real’ Property such as land, buildings and fixtures which together with moveable Property or ‘chattel’ (derived from the Anglo-Saxon for cattle) constitute tangible Property. Then there is intangible Property such as business ‘good will’ and intellectual property such as copyrights, patents, registered industrial designs and trademarks. Each of these rights & obligations are granted by and subject to the pleasure of the Sovereign whether Crown or State. In Law each consists of different bundles of rights & obligations, e.g., the term of a patent vs. copyright. With respect to ‘real’ Property there are two principal forms of Title. First, allodial Title refers to absolute ownership without service or acknowledgement of or to any superior. This was the practice among the early Teutonic peoples before feudalism. Allodial ownership is, however, virtually unknown in Common Law countries because ultimately all Property is subject to the Sovereign – Crown or State. In this sense there is no such thing as absolute private property. Second, fee simple or ‘freehold’ is the most common form of Title and the most complete short of allodial. It should be noted that the ‘fee’ refers not to a payment but to the estate or Property itself as in the feudal ‘fief’. Fee simple is, however, subject to four basic government powers - taxation, eminent domain, police and escheat (derived from the feudal practice of an estate returning to a superior Lord on the death of an inferior without heir). In addition, fee simple can be limited by encumbrances or conditions. These may include limitations on exclusive possession, exclusive use and enclosure, acquisition, conveyance, easement, mortgage and partition. In addition it may or may not include water rights, mineral rights, timber rights, farming rights, grazing rights, hunting rights, air rights, development rights and appearance rights. Proprietors may, subject to limitations in their Title, lease, let and/or rent their real Property. In the Civil Code tradition the legal right to use and derive profit or benefit from Property belonging to another person (so long as it is not damaged) is called ‘usufruct’ from the Latin meaning ‘use of the fruit’, not ownership of the tree. In Common Law, one might call it ‘tenant title’. It does not constitute legal Title but does entitle the holder to use the Property and to have that right enforced by the State against the legal Titleholder and others.

Finally, there is occupancy or possession-based Title. In effect,

this invokes ‘squatter’s rights’. It does not represent legal Title.

Nonetheless, if possession by occupancy is not disputed it may, in time, become

legal Title. At the very extreme is the question of

John R. Commons observed in his classic

The Legal Foundations of Capitalism

There are five categories of public property under Roman law: res nullius, res communes, res publicae, res universatitis and res divini juris. To begin, the Latin word res means ‘thing’. Res nullius refers to things that are unowned or have simply not yet been appropriated by anyone such as an unexplored wilderness. Res communes refers to things that are open to all by their nature, such as oceans and the fish in them. Res publicae refers to things that are publicly owned and made open to the public by law. Res universitatis refers to things that are owned by a body corporate, i.e., within the group such things may be shared but not necessarily outside the group. There are thus 'club goods' or quasi-public goods, free to members but not to non-members. Finally, res divini juris (divine jurisdiction) refers to things ‘unownable’ because of their divine or sacred status (Kneen 2004).

As has been seen through international agreements (as well as

domestic developments) the concept of Property has expanded to include Common

Natural Resources such as the Law of the Sea,

Biodiversity, Carbon Dioxide and Intangible Cultural Property.

Domestically Intellectual Property Rights are an example how the State by

establishing property rights creates markets. Some observers have

recognized that this ability to define new forms of property represents a

critical tool of the State in management of a national economy. Please

see:

c) Regulation (MKM C15/341-2; 225-226, 346-348; 323-324) In a sense all State intervention in the economy involves regulation. Legislation sets out the strategy and tactical means for politically justified intervention but the logistics, where the rubber hits the road, takes the form of rules & regulations, practices & procedures often developed and always enforced by the bureaucracy. In the case of State intervention justified by Equity, a price ceiling, e.g., rent control, or a price floor, e.g., minimum wage, must be enforced by inspectors and their support staff, plant & equipment. The associated cost of State enforcement does not appear in the analytic geometry of the Standard Model. In addition there are compliance costs (filling out forms and answering questions) paid by either the producer or consumer but also not reflected geometrically.

In the case of State intervention justified by Market

Power a bureaucracy must be built that, in effect, monitors the

production and cost functions of a monopoly or collusive oligopoly.

This requires knowledge of the industry that usually can only be learned

on the job. In turn this means the bureaucracy or regulator must

include those who formerly worked in the industry or regulatee.

Overtime this can lead to the regulator being 'captured' by the

regulatee, i.e., increasingly sympathetic towards the regulatee's

position vis-a-vis consumers. Thus in directing the

industry towards a competitive outcome t

In the case of State intervention justified by

Externalities the first cost is detection, i.e., determining

there is an externality and, in the case of a negative externality like

pollution, what is its sustainable economic level? This is usual

accomplished through scientific or policy research. Then follows

Legislation and then Rules & Regulations.

2.

3.

In all three options one question remains unanswered: What

is the nature of public administration especially regulation? As

noted by Philip K. Howard in

The Rule of Nobody : Saving America from Dead Laws and Broken Government,

W. W. Norton & Company, April 14, 2014 modern bureaucracy is

governed by detailed regulations intended to eliminate arbitrary

decisions by bureaucrats. This follows from Voltaire's call “Let

all the laws be clear, uniform and precise” suggesting that otherwise

judges and officials will mess things up: “To interpret laws is almost

always to corrupt them” (Howard, 2014,16). The result is that:

“The process is aimed not at trying to solve problems,... but trying to

find problems. You can’t get in trouble by saying no”

According to the OED, a subsidy is: "Money or a sum of money granted by the state or a public body to help keep down the price of a commodity or service, or to support something held to be in the public interest. Also: the granting of money for these purposes." The form and purpose of a subsidy varies. It can assist consumers by reducing the cost of a good or service, for example, student bursaries and grants. In effect at each market price the subsidy reduces the cost to a consumer shifting the demand curve to the right. It can also reduce the cost of production so that at each possible market price the cost to producers is reduced shifting the supply curve to the right, e.g., subsidies to solar and wind power. A subsidy may also take the of tax expenditures, a reduction in revenue. To quote Wikipedia: A tax expenditure program is government spending through the tax code. Tax expenditures alter the horizontal and vertical equity of the basic tax system by allowing exemptions, deductions, or credits to select groups or specific activities. For example, two people who earn exactly the same income can have different effective tax rates if one of the tax payers qualifies for certain tax expenditure programs by owning a home, having children, and receiving employer health care and pension insurance. Defining what constitutes a subsidy to production is one ongoing challenge facing the World Trade Organization. f) Taxation (MKM C8/171-181; 159-70; 172-183; 158-165)

T

INTRODUCTORY MICROECONOMIC SUMMARY IN 12 GRAPHS

|

Natural resources had to be shaped by labour to have any value.

They were a cost free input. This is the Labour Theory of Value.

Unlike the Standard Model that takes market price as the measure of

value, the Labour Theory argues value is measured by labour content

-

Natural resources had to be shaped by labour to have any value.

They were a cost free input. This is the Labour Theory of Value.

Unlike the Standard Model that takes market price as the measure of

value, the Labour Theory argues value is measured by labour content

-  This applies not

just in the Natural & Engineering Sciences but also in the Humanities &

Social Sciences as well as the Arts. Take the artist Van Gogh who

spent much of his life in an insane asylum, cut off his ear and sent it

to his girlfriend yet out of all his pain and suffering came

This applies not

just in the Natural & Engineering Sciences but also in the Humanities &

Social Sciences as well as the Arts. Take the artist Van Gogh who

spent much of his life in an insane asylum, cut off his ear and sent it

to his girlfriend yet out of all his pain and suffering came