Microeconomics

Macroeconomics

SISTERetrics

SITES

Compleat World Copyright Website

World Cultural Intelligence Network

Dr. Harry Hillman Chartrand, PhD

Cultural Economist & Publisher

©

h.h.chartrand@compilerpress.ca

215 Lake Crescent

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan

Canada,

S7H 3A1

Launched 1998

|

Microeconomics 6.0 Market Failure

|

|

|

The necessary conditions for Perfect Competition are so strict that it does not, in fact, exist in the real world. It is an ideal, an ideological benchmark against which outcomes under Imperfect Competition can be assessed. This includes, to a degree, Oligopoly where the Standard Model comes to its geometric end with Sweezy's Kinked Demand Curve. Since the 1940s constrained profit maximization under Oligopoly has mutated into Game Theory which operates outside the geometric elegance of the Standard Model. Nonetheless, if one uses Perfect Competition as the benchmark then outcomes under Imperfect Competition represent Market Failure to allocate sufficient resources to attain a perfectly competitive price/quantity outcome, a.k.a., allocative inefficiency. There are, however, other forms of Market Failure. These include Externalities, i.e., costs and benefits external to market price, and Public Goods, i.e., socially valuable goods and services that firms cannot profitably produce or that the Public does not want them to produce, e.g., national defense. Put another way, we have, up to now, implicitly assumed that all relevant benefits and costs of production are reflected in market price paid by the consumer and received by the producer. What happens if we relax that assumption? In what follows the nature of and alternative policy solutions to different forms of Market Failure are examined. Finally, the nature and limitations of Public Choice Theory will be considered, i.e., How is Public Choice made to mitigate pernicious effects of Market Failure?

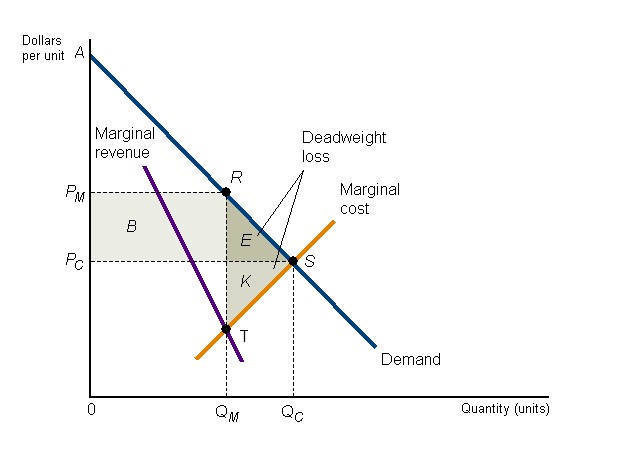

Unlike

Perfect Competition under all forms of Imperfect Competition producers

supply a smaller quantity at a higher price, generate a deadweight loss of consumer & producer surplus

while some consumer surplus is appropriated as excess,

economic or monopoly profit.

Furthermore, in the long run Imperfect Competition fails to attain the

lowest average cost per unit output.

Under Imperfect Competition firms are thus price makers rather than price takers as under Perfect Competition. They exercise Market Power defined as the ability to determine the price/quantity outcome in the market. The Public Choice is whether Equity requires intervention to protect consumers? Whether or not Equity or any other moral principle justifies public intervention in the marketplace is considered in 4. Public Choice. i -Monopoly (MKM C15/331-4; 312-15, 345-349; 322-325) In the case of Monopoly the sources of Market Power may be: (a) economies of scale/network economies resulting in a Natural Monopoly; (b) exclusive possession of a critical input to the production process; (c) State grant of intellectual property rights (IPRs) such as copyrights, patents, registered industrial designs or trademarks; and/or, (d) State grant of a public francise over a natural monopoly or grant of self-regulating authority, e.g., to accountants, architects, dentists, engineers, lawyers and medical doctors, a.k.a., the self-regulating professions or the Practices: a) in the case of a Natural Monopoly rooted in economies of scale, one firm can satisfy all market demand at the lowest possible average cost (MKM Fig. 15.1). In response to any entrant the monopolist can drop price below the break-even point of any aspiring rival. There are at least two policy solutions. The first is to place the Monopoly under public ownership. This a generally done only when output is considered critical to public welfare, e.g., municipal water and sewage systems. The technical term is a 'franchise'. The second alternative is to regulate the Monopoly in an attempt to reduce price and increase quantity approximating the outcome of Perfect Competition. Net economies enjoyed by firms in the global knowledge-based/digital economy (KB/DE) present a new problem for the State. Traditionally the test has been higher prices to consumers and how to lower them. In the KB/DE many services have no market price, zero $s - Google maps & search, Facebook, Twiter, Youtube, Instagram ...... The price paid is personal information monetized as targeted psychographic advertising - commercial and political. Currently governments around the world are examining how to deal with the information/content net economies enjoyed by the Tech monopolies. For those interested, please see (non-testable): The Unfinished Revolution: Arts Management in a 21st Century Knowledge-Based/Digital Economy, June, 2019. Value without Price or Value Theory Redux, Compiler Press, May 13, 2018 Disruptive Solutions to Problems associated with the Global Knowledge-Based/Digital Economy, Compiler Press, Oct. 2016; b) in the case of a Monopoly based on exclusive possession of a physical input there are also at least two policy solutions - break up the monopoly into a number of smaller, competing firms or regulate it. The classic case is Standard Oil of New Jersey founded by John D. Rockefeller Sr. The firm controlled virtually all oil and oil refining in the U.S.A. In 1911 the Supreme Court of the United States broke up the firm into 34 separate companies; c) in the case of a Monopoly based on IPRs, there are three alternative policy solutions - break up the monopoly, regulate it or amend its IPRs. Thus Microsoft was, like Standard Oil, threatened with break up during the Clinton administration in the 1990s. It was proposed to break up the firm into three distinct companies - one each for Windows operating system, Office applications and Server software. The subsequent George W. Bush Administration choose to regulate. In the European Union, however, Microsoft was required to open up its 'interface’ code to competitors to allow their products to work smoothly with Windows and thereby compete in the marketplace. This 'interface’ was unpublished and treated as a trade secret by Microsoft as remains the case with the ‘kernel’ of its operating system. Alternatively IPRs can be legally amended, e.g., requiring compulsory licensing, shortening duration or abrogating some or all rights; and, d) in the case of a Monopoly based on a State grant of self-regulating authority, a.k.a., the Practices, there are a number of policy solutions: (i) change their charters; (ii) regulate their procedures and rates, e.g., under Medicare; (iii) pass profession-specific legislation, e.g., the U.S. Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002, also known as the "Public Company Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act"; or, (iv) as in Germany and Austria, make the Practices constitutionally recognized and accountable for their actions and standards. ii - Monopolistic Competition (MKM C16/356-9; 336-8, 361-363; 332-334) In the case of Monopolistic Competition, with many small firms, the source of Market Power is product differentiation. However, while in the short run excess, economic or monopoly profits are earned, in the long run excess profit is eliminated by free entry into the marketplace (MKM Fig's 16.2 a & 16.3). The Public Choice is whether product differentiation is worth the added cost to consumers? Generally the answer is yes and the State does not intervene other than for health and safety reasons. iii - Oligopoly (MKM C17/383-7; 360-3, 386-391) In the case of Oligopoly a few large firms dominate the industry accompanied by a competitive fringe of smaller firms. Market Power under Oligopoly generally results from some combination of: (a) economies of scale/network economies; (b) process/product differentiation; (c) process/product innovation; (d) collusion; and/or (e) legal tactics. In the case of economies of scale, if there are several competing firms break up is not usually a policy option. With respect to product differentiation and innovation Public Choice involves determining whether such benefits out weigh the added cost to consumers. In this regard it is important to note that under Perfect Competition firms are lean, mean fighting machines with no excess profit to finance long term research and development leading to innovation or to launch major advertising campaigns. It is, however, with respect to collusion that regulation, e.g., of the Canadian cell phone industry, is not an option but rather a necessity involving competition policies that, among other things, prohibit price fixing which is common in oligopolistic industries. As with a regulated monopoly, regulation of an oligopoly begins with an estimate of the price/quantity under perfection competition (or a milder form called 'workable competition'). To do so an estimate of the supply/marginal cost curve is necessary but obtaining the 'real' data is often accompanied by an imperfect competitor 'padding' costs, effectively shifting the supply curve to the left, raising market price and lowering output, thereby preserving some of its economic profit even under regulation. This can also be accompanied by what is called 'the regulator being captured by the regulatee". Problems associated with regulation are discussed in more detail below under 4. Public Choice.

2. Externalities (MKM C10/211-231; 198-216, 218-238; 201-219)

Until now we have assumed that the market price for a good or

service includes or

internalizes all relevant costs and benefits. This means the

consumer captures all the benefits and the producer pays all the costs.

Such goods & services are called perfectly private goods. An externality refers to costs or benefits not captured by market

price, i.e., they are external to market price. In effect,

the market demand curve reflects

only the

marginal private benefit

(MPB) curve of consumers but not external benefits to society

as a whole. When external benefits are added, vertically, to the

market demand curve we derive the

marginal social benefit

(MSB)

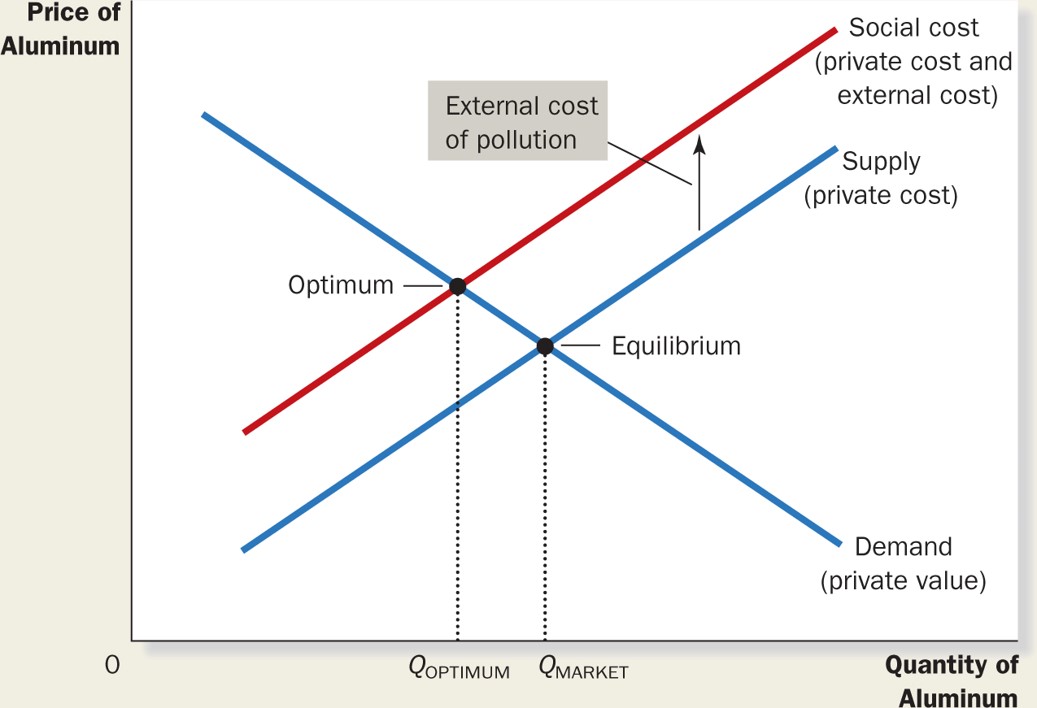

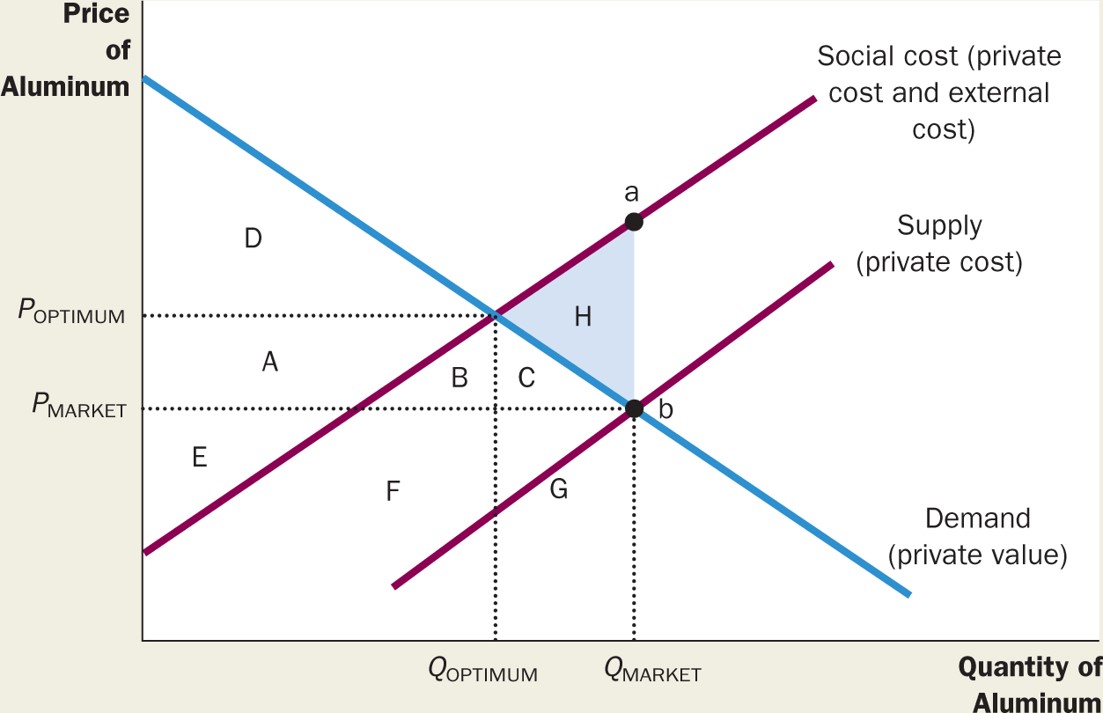

Similarly, if there are external costs to production, i.e., not explicit costs to the producer, the market supply curve reflects only the marginal private costs (MPC) not costs external to the firm’s bottom line, e.g., pollution costs that society must pay. When social costs are added, vertically, to the market supply curve we derive the marginal social cost (MSC) curve inclusive of both private and public costs. The Standard Model is based on the assumption that all relevant costs and benefits are internalized in market price, i.e., there are no externalities. If this is true then ‘X’ marks the spot. If, however, there are externalities then market equilibrium is not allocatively efficient nor is the greatest good for the greatest number achieved. If a social optimum equilibrium is to be achieved then a Public Choice must be made as to the costs and benefits of intervention in the marketplace and alternative public policy solutions to mitigate negative externality-generating goods (demerit goods) and foster positive externality-generating ones (merit goods). The appropriateness of public intervention in general including Market Failure due to Externalities is discussed under 4. Public Choice. Ideally, external or social costs and benefits should be added to private costs and benefits reflected not by market supply and demand curves but rather by the MSB & MSC curves. The point is that external costs must be paid and external benefits must be accounted for if the socially optimal price/quantity equilibrium is to be established. The agency to do so is not the market but rather the State. Put another way, the market 'X' solution is superseded by a social ‘X” marking the spot where allocative efficiency exists and achieves the greatest good for the greatest number. It is thus up to the State to correct the miscalculation of private agents to achieve a socially optimal equilibrium. We will now examine examples of negative and positive externalities and alternative public policy solutions i - Negative Externalities (MKM C10/214-17; 201-4, 221-224; 203-206)

There are many forms of negative externalities but the most

widely recognized is environmental pollution. Recognition of such

negative externalities tends to be the result of increasing

a) air pollution mainly caused by road transportation and industrial processes;

c) land pollution mainly caused by

industrial waste and by consumers d) sound and light pollution mainly caused by urbanization; and,

e) water pollution mainly caused by

industrial waste (land and sea) and farm run off.

With respect to production, firms do not internalize

external costs because they are not out-of-pocket expenses and therefore

are not reported in the firm's bottom line (MKM Fig. 10.2).

N

T

Arguably externalities arise due to a lack of property

rights

I

c) Regulation

I

By contrast, subsidies can be used to reduce the cost of substitutes (cross elasticity). Thus subsidies to nuclear, solar and wind power should reduce demand for coal, gas and oil in turn reducing pollution and its external costs.

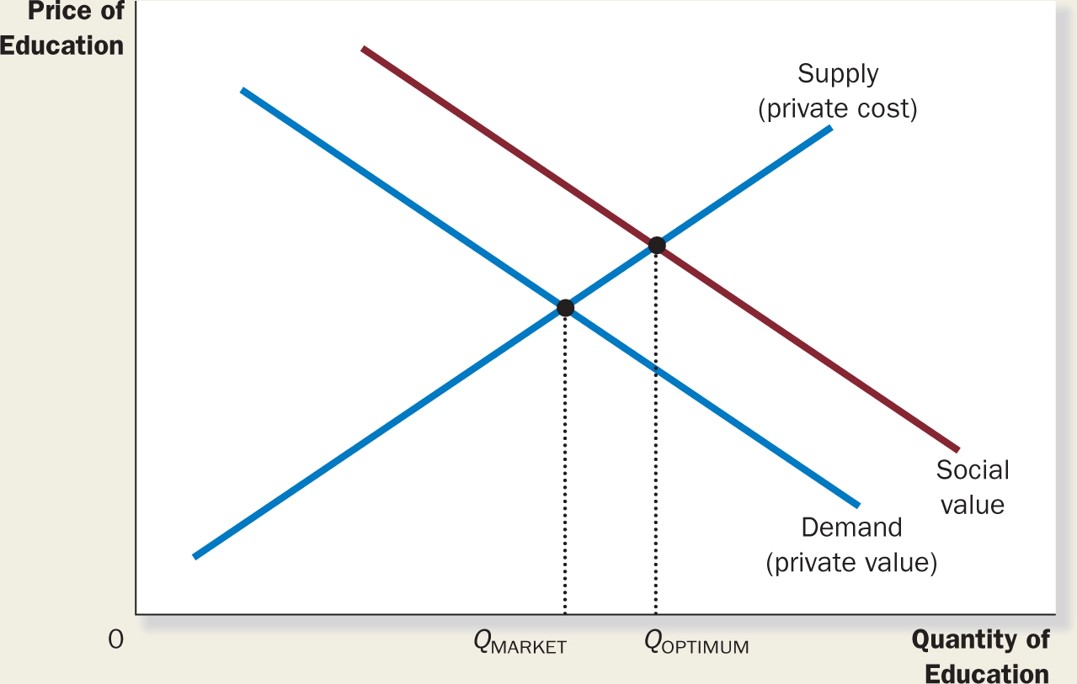

ii - Positive

Externalities

There are two principle ways to achieve the socially optimal level of

education. The first is to subsidize the supplier, e.g.,

State grants per student to universities and colleges, shifting the

supply curve to the right, lowering the price of tuition and encouraging

more students to stay in school, ideally at the optimum level. The

second is to subsidize students, e.g., bursaries, grants, loans,

scholarships, etc., effective lowering the cost of

education and shifting the demand curve to the rights until, ideally, it

merges with the MSB curve leading to a socially optimal outcome

There are also private positive

externalities such as good neighbourhood effects including well kept

lawns, flower beds, etc., that cost the pssing visitor nothing but

pleasure. There are in fact a range of

merit goods that the State chooses to support because of their positive

externalities. Examples include the Arts, scientific and

industrial research & development and many other non-profit or Third

Sector activities. Subsidies are provided by the State in the form

of

|

This leads

to a lower price and higher output relative to the social optimum.

It also means that society as a whole must pay these external costs,

e.g., increased health and/or purification costs and suffer a

deadweight loss of producer and consumer surplus (MKM Fig. 10.3).

This leads

to a lower price and higher output relative to the social optimum.

It also means that society as a whole must pay these external costs,

e.g., increased health and/or purification costs and suffer a

deadweight loss of producer and consumer surplus (MKM Fig. 10.3).

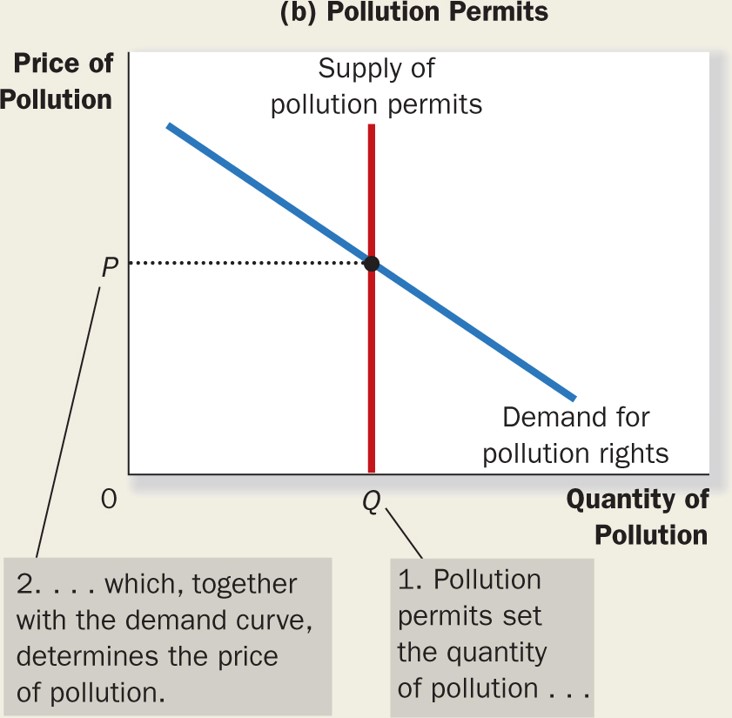

Exceeding the permitted level leads to increased

competition for permits or punitive penalties enforced through the

courts.

Exceeding the permitted level leads to increased

competition for permits or punitive penalties enforced through the

courts.