Microeconomics

Macroeconomics

SISTERetrics

SITES

Compleat World Copyright Website

World Cultural Intelligence Network

Dr. Harry Hillman Chartrand, PhD

Cultural Economist & Publisher

©

h.h.chartrand@compilerpress.ca

215 Lake Crescent

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan

Canada,

S7H 3A1

Launched 1998

|

Macroeconomics 5.0 Fiscal & Monetary Policy (cont'd)

|

|

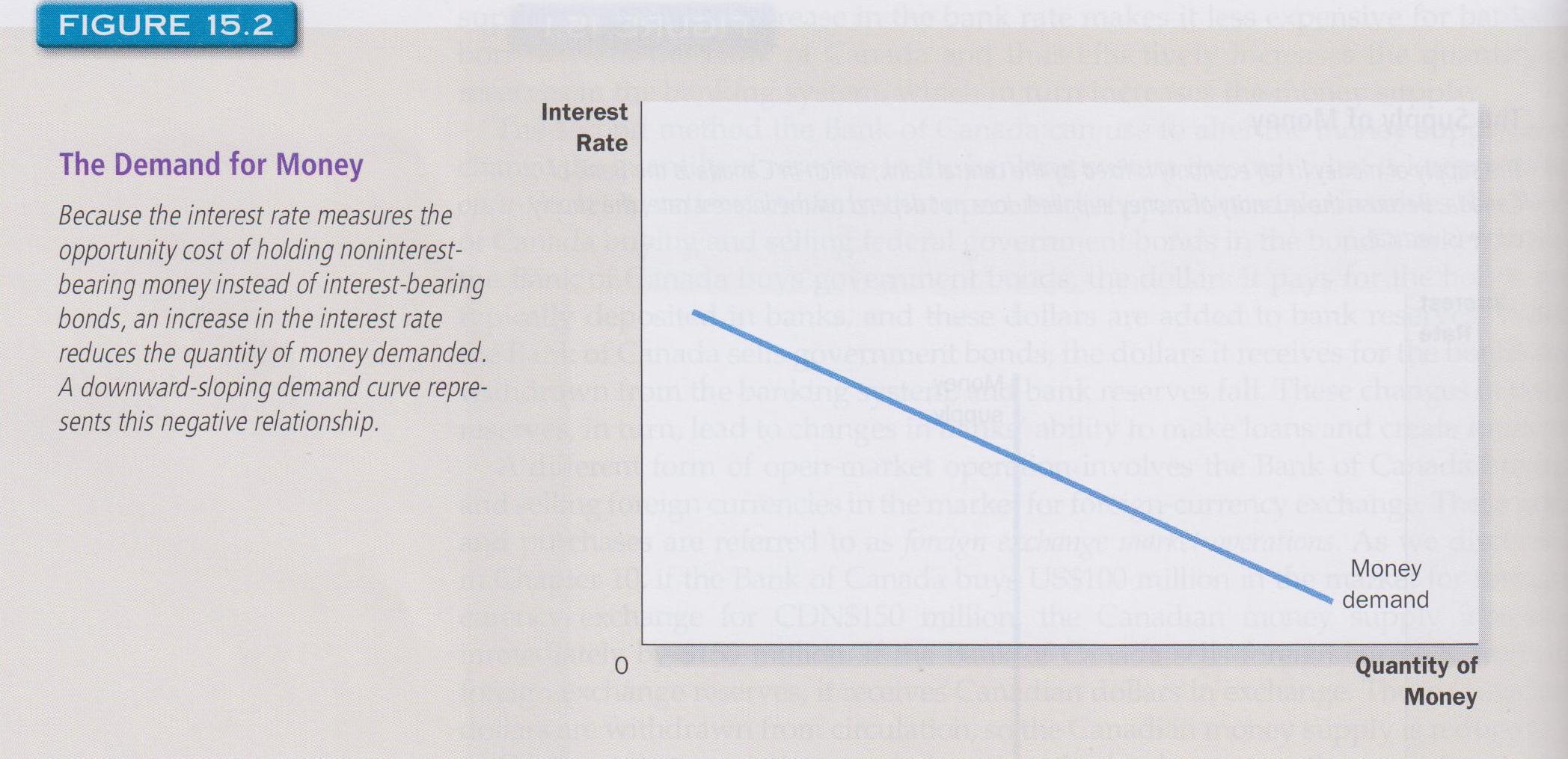

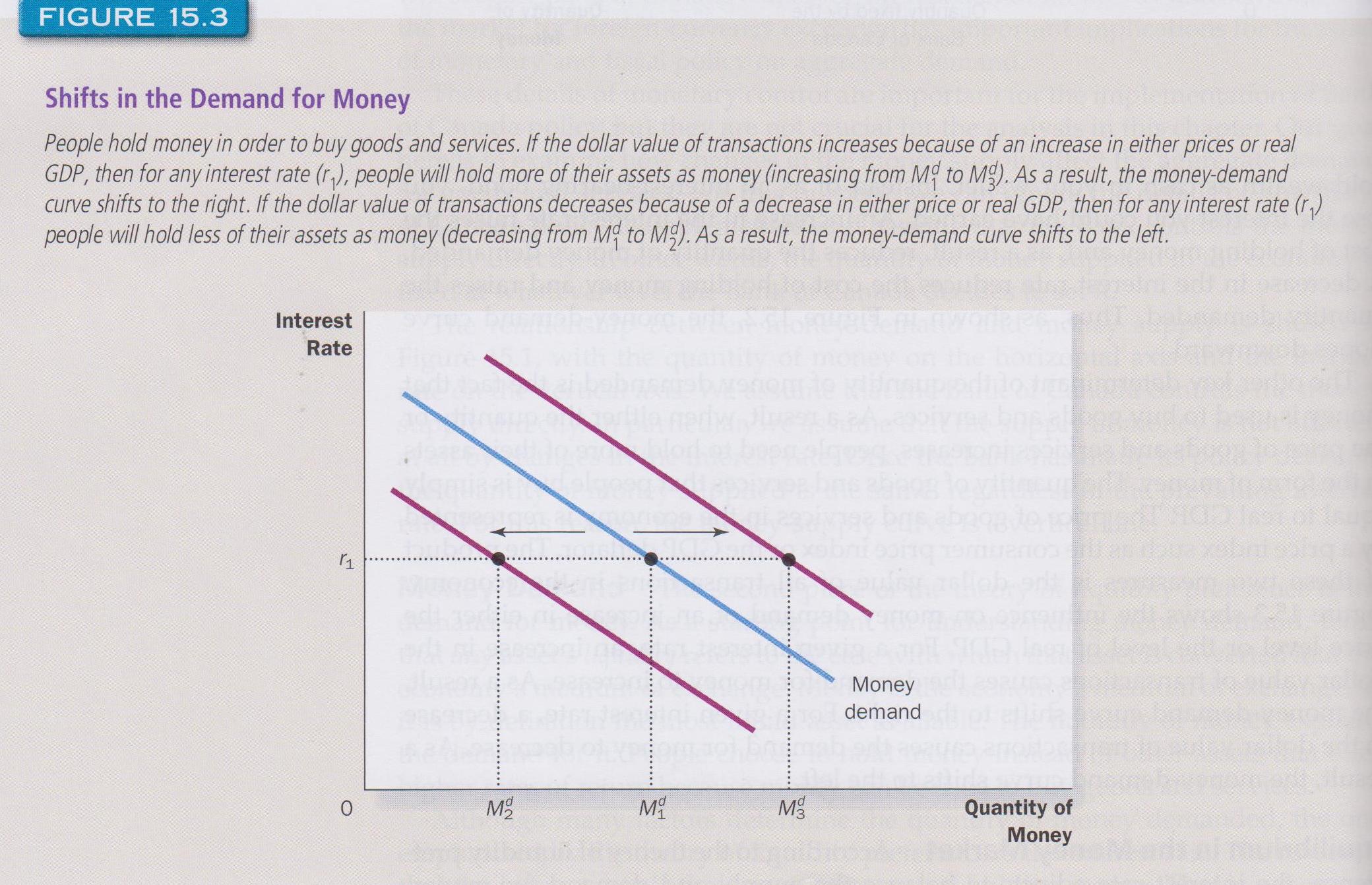

1. Demand for Money (MKM 378-79: 354-55; 364-365; 339-340) There are three demands for money. First, there is a transactional demand for example at the end of the month to pay the bills. Between payment periods there is no transactional demand. Again, this time lag allows banks to loan out deposits and thereby create new money. Second, there is a precautionary demand for money. What if the banks closed and the ATM is down? I need cash for the grocery store! For purposes of the simplified model, however, precautionary is consider a form of transactional demand, i.e., demand for money to meet unanticipated transactions. Third, there is speculative demand for money. Speculative demand for money (sometimes called asset demand) is an original contribution of Keynes. His so-called Classical predecessors recognized only transactional demand. They believed no rational person would simply hold cash. Rather it would be used to buy goods & services or invested/saved to yield income as interest. Stuffed in a mattress it does neither. Monetarists similarly believe there can be no hoarding of cash. In their case it is argued that if bonds are not appealing then real estate will be and if not then artwork or some other form of income earning asset, i.e., there will be no hoarding. Keynes, on the other hand, argued that given uncertainties about future interest rates there would be times when individuals would hold on to cash. If you buy a bond today you are committing part of your income to something that will pay a given rate of interest. The price of the bond is called its yield measured by its purchase price and its interest rate say 5%. If tomorrow the interest rate increases to 10% to sell your bond it must yield an effective rate of 10%. The difference between what you paid for the bond and the price at which you must sell it to generate the 10% yield is called a capital loss. For example, while the old bond cost you $1,000 and generates a 5% return, it must be sold tomorrow for only $500 to yield 10%. At very lower rates speculative demand will be very high in anticipation that interest rates must rise tomorrow. If enough individuals and institutions hold cash rather than lend or invest it then a liquidity trap may be created. This is the point at which the demand for money is perfectly elastic with respect to the interest rate. Banks, for example, will not lend because they believe interest rates are so low that they must rise. Accordingly they will not lend to firms for investment purposes or to consumers fearing capital loss. Four factors affect demand for money. The first is the price level. The quantity of money measured in current dollars is called the nominal money supply. The quantity of nominal dollars demanded is proportional to the price level. If prices go up, the demand for nominal money goes up. What in the end matters, however, is not nominal but real money demanded, that is, its purchasing power. Thus if prices go up 10% and income goes up 10%, nominal money has increased but real money stays the same. Thus inflation tends to lower the value of money over time. The higher the rate of inflation, the greater will be the demand for nominal money today. The second is interest rates. Like all commodities, the price of money is an opportunity cost. If its price goes up, consumers and producers will tend to substitute less expensive alternatives. The price of money is the interest rate. The higher the interest rate the more expensive is money and the less will be demanded. Thus an alternative to holding money (the opportunity foregone) is to purchase an interest-earning asset. The third force affecting demand for money is real GDP. In short, the higher is the level of income the greater is the transactional demand for money, i.e., the larger the economy the greater the number of transactions and therefore the greater the transactional demand for money. Fourth is financial innovation and payment habits. Innovations like interest-earning chequing accounts, ATMs, debit and credit cards all reduce the demand for money. Similarly if you are paid once a year you will hang on to money increasing demand while if you are paid weekly you know there is more coming quickly and you spend or invest. iii - The Money Demand Curve (MKM C15/378-83: 354-59; 364-366; 339-342) The demand curve for money (R&L 13 Ed Fig. 28-1) relates the quantity of money demanded (transactional plus speculative or asset demand) and its price - the interest rate. While transactional demand is relatively inelastic with respect to the interest rate at a given price level and GDP, speculative demand is downward sloping with respect to interest rate, a.k.a., the price of money. The total demand curve is therefore negatively or downward sloping from the left with respect to the interest rate. A shift in the demand curve for money can occur, for example, if real GDP changes, if the aggregate price level rises, if financial innovation takes place or if payment habits change.

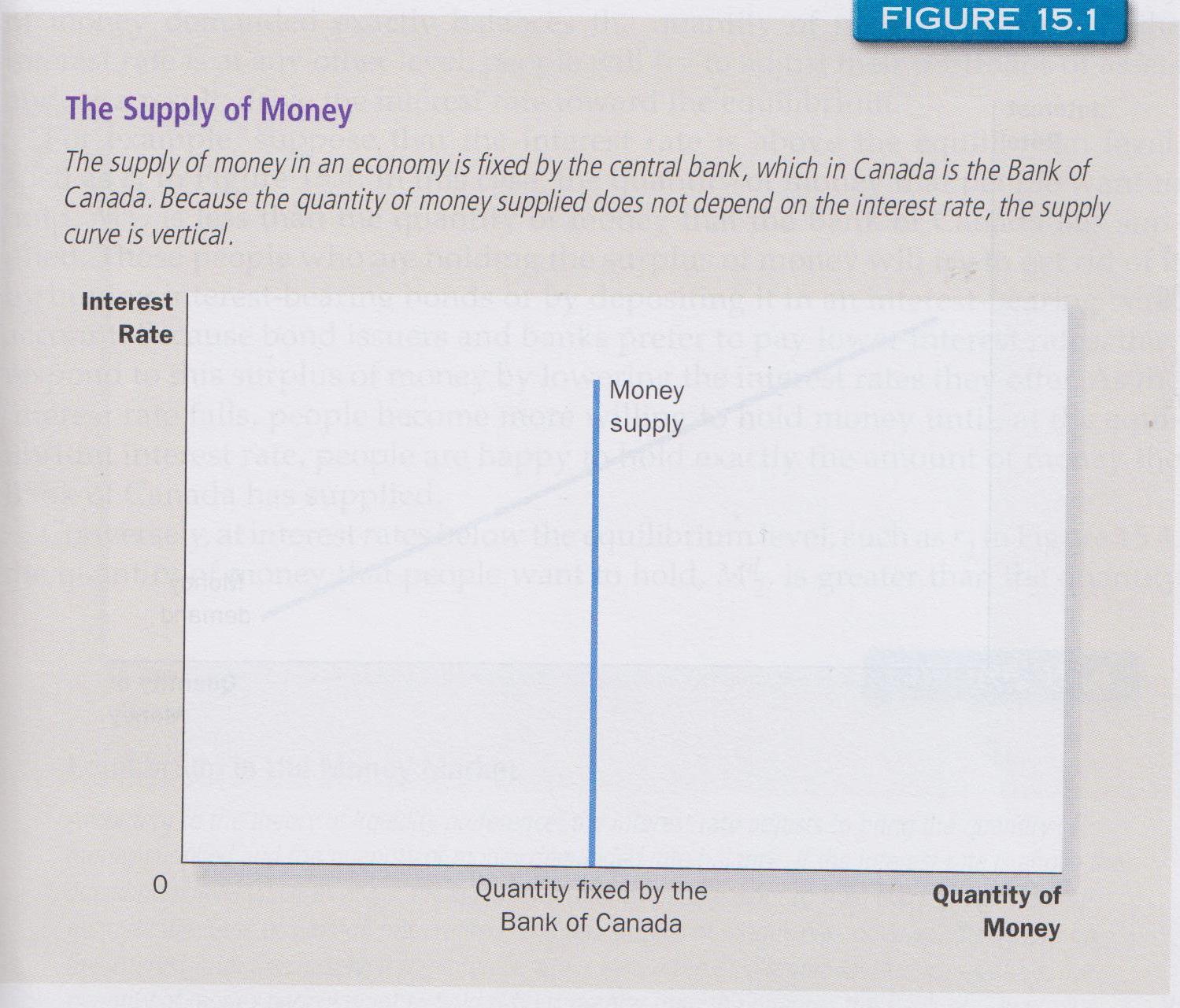

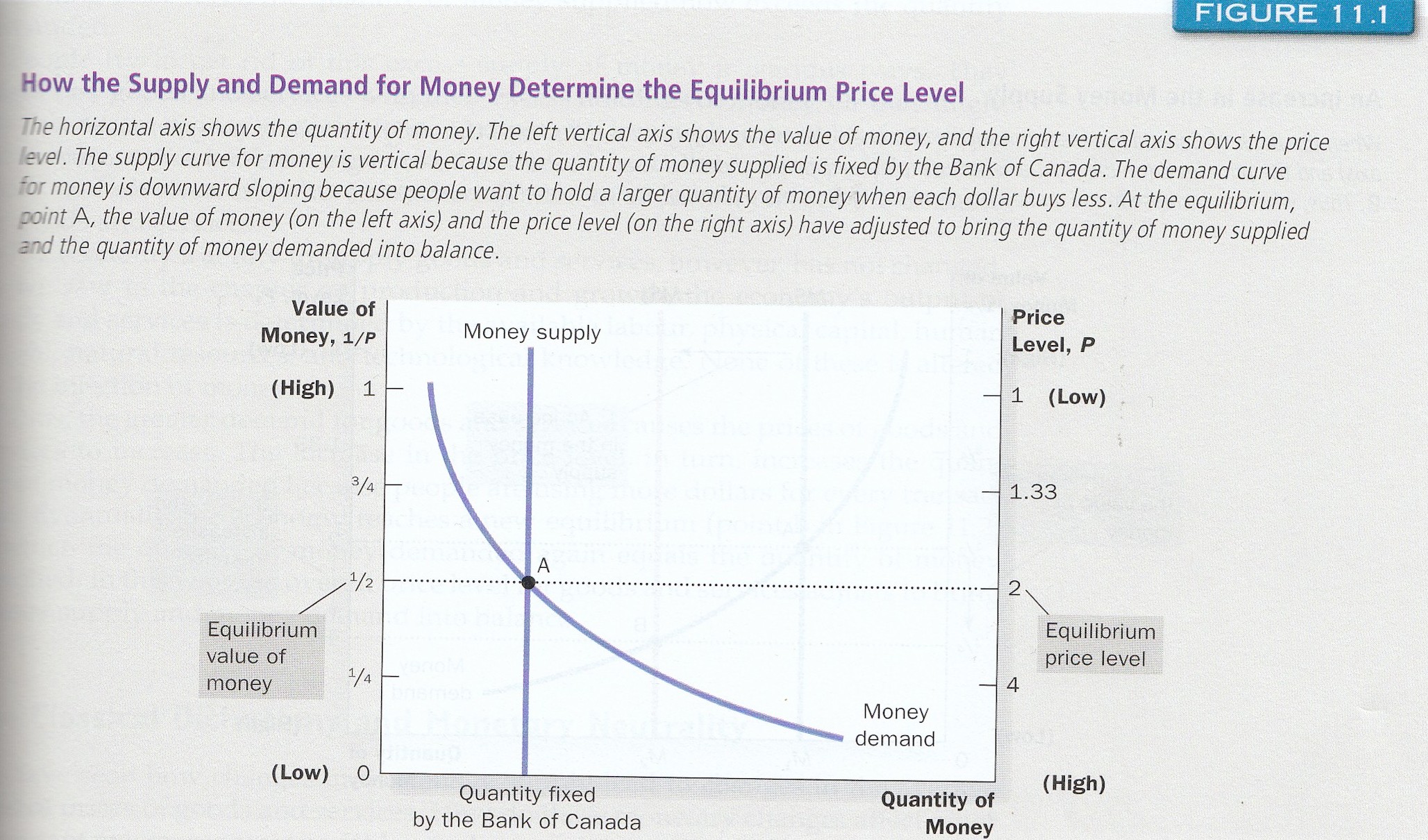

It is assumed for purposes of the simplified model that the supply of money is determined by the central bank. Even super money cannot escape the control of the central bank. If the wealth effects of a stock market boom are big enough and money is in effect being created, the central bank can raise interest rates and choke off the boom. Similarly during a slump the central bank can lower interest rates and assist recovery. The objectives and tools of the central bank will be considered below. ii - Supply Curve (MKM C15/377-8: 353-54; 363-365; 338-341)

Accordingly the supply curve (R&L 13th Ed

Fig. 28-4,

Fig. 28-5; MKM Fig. 15.1) for money is

vertical and perfectly inelastic. The curve will shift only on the

decision of the central bank.

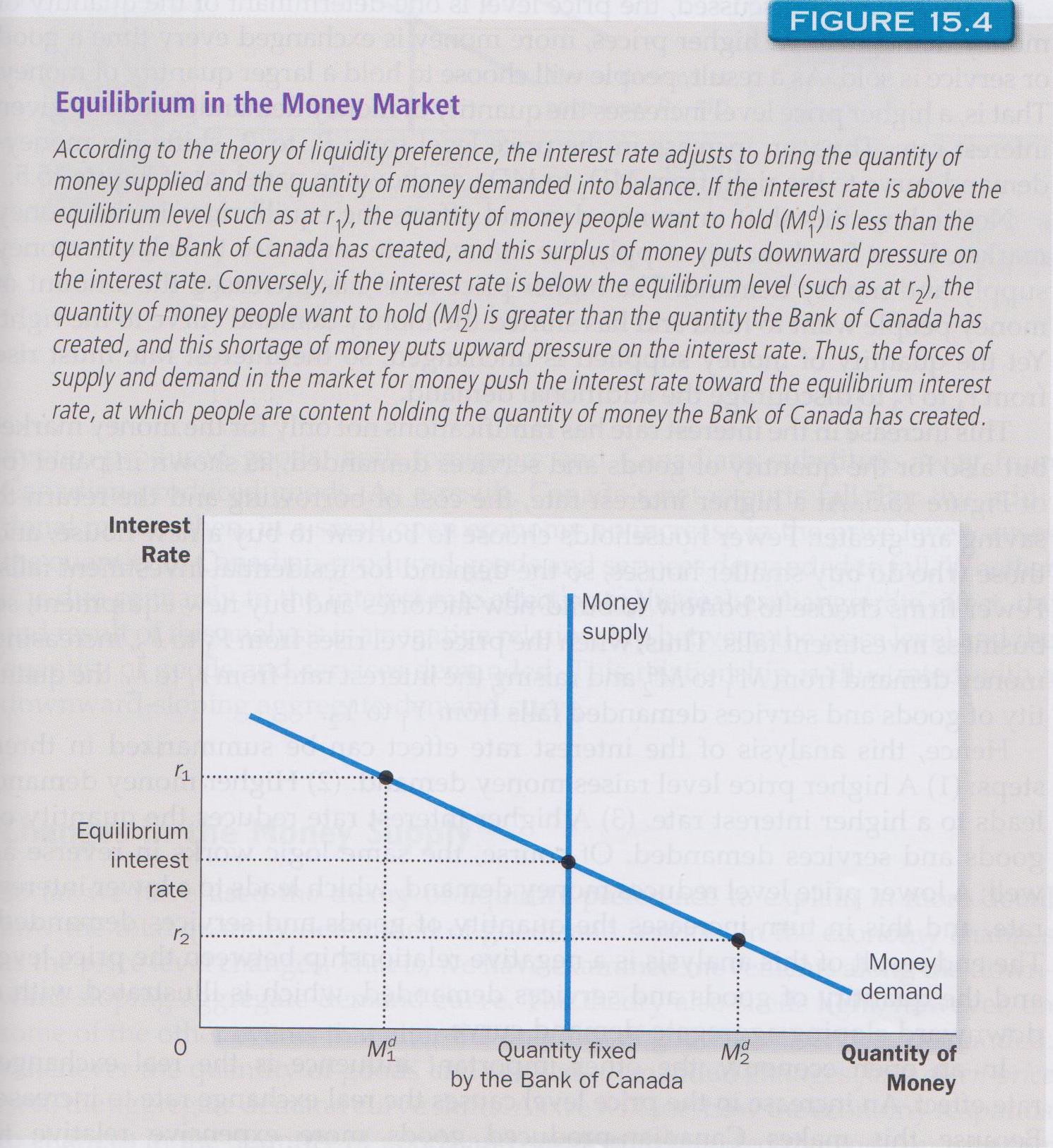

4.2.3 Market Equilibrium (MKM C 15/379-383: 356-59; 366-368; 340-344) Money market equilibrium will occur where the vertical supply curve intersects the downward sloping demand curve. ‘X’ marks the spot yet again (R&L 13 Ed Fig. 28-2; MKM Figs 11.1 & 15.4). The connection between monetary policy and the real economy is the interest rate. As the interest rate goes up investment goes down shifting the aggregate demand downward to the left. If the interest rate goes down then investment goes up and the aggregate demand curve shifts up to the right (R&L 13 Ed Fig. 28-3). By controlling the money supply the central bank can thus increase or decrease the interest rate and thereby affect investment and the real economy (R&L 13 Ed. Fig. 28-4, Fig. 28-6, Fig. 28-7).

|