Microeconomics

Macroeconomics

SISTERetrics

SITES

Compleat World Copyright Website

World Cultural Intelligence Network

Dr. Harry Hillman Chartrand, PhD

Cultural Economist & Publisher

©

h.h.chartrand@compilerpress.ca

215 Lake Crescent

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan

Canada,

S7H 3A1

Launched 1998

|

Microeconomics 5.0 Competition (cont'd)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

5.3 Monopolistic Competition (MKM C16/351-67; 330-44; 355-370; 331-345)

i - Anonymity

Like

ii - No Market Power While there is a large number of firms, product differentiation offers sellers a degree of market power. Given that some consumers prefer the goods & services of one producer over another permits, as will be seen, a price higher than under Perfect Competition. In effect the market demand curve is disaggregated into distinct market clusters, segments or niches, e.g., restaurants. It is important to note, however, that the demand curve for one firm or one niche is affected by the price of other firms and other niches. Thus an increase in price by a competitor shifts the firm's demand curve up to the right; a decrease causes a shift down to the left (cross elasticity). This is because while differentiated, output of one firm or niche is a close substitute for those of other firms and niches. Compared to Monopoly, market power is therefore more limited. iii -Perfect Knowledge

iv -

Free Entry & Exit As in Perfect Competition there is free entry and exit. If excess profits are earned in a given 'niche' firms in other niches can easily convert their capital plant & equipment, e.g., a Greek restaurant has a fully equipped kitchen, tables & chairs, cutlery, cash registers and can, relatively easily, be converted into a fish & chips restaurant.

2. Marginal Revenue Curve Let us assume a firm, entrant or existing firm, innovates a newly differentiated product, e.g., Afghani roast lamb. In the short run that firm is the only producer. In effect, it is a monopolist facing the niche demand alone. It can sell more if it lowers price; it loses sales if it raises its price. Like a monopolist it therefore has a downward sloping marginal revenue curve. Furthermore, its marginal cost curve is the niche supply curve.

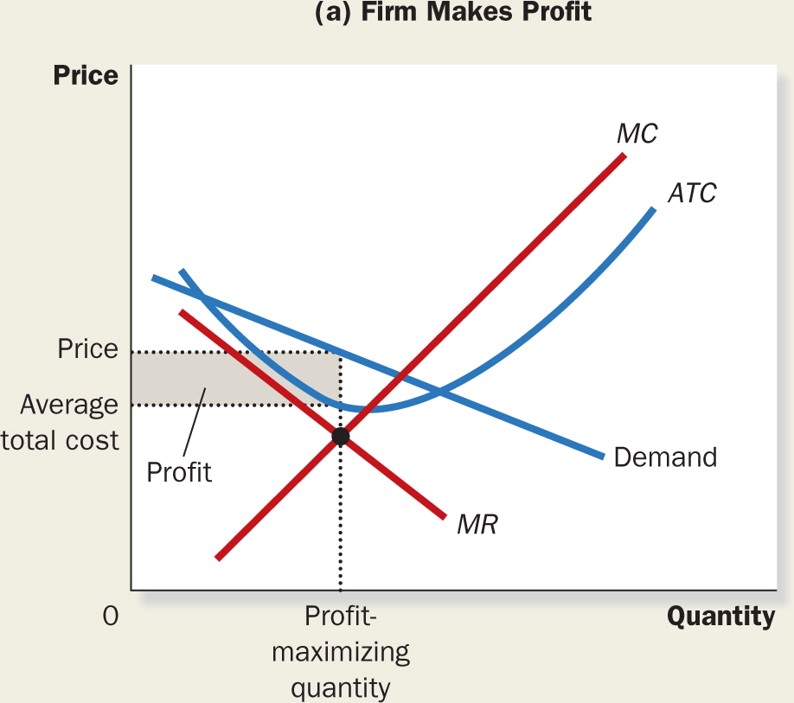

3. SR Equilibrium (MKM C16/354-5; 333-34; 358-359; 334-335) In the short-run equilibrium of the initial entrant will be reached where marginal cost equals marginal revenue, i.e., profit maximizing - the cost of the last unit equals how much it earns but all previous units cost less (MKM Fig. 16.2). MKM C16/Fig's 16.2a & 16.3

The outcome is identical, in the short-run, to Monopoly. This includes similar costs. Output is less than under Perfect Competition. Price is higher. There is a deadweight loss of both consumer and producer surplus. Finally, part of consumer surplus is appropriated as economic profit. These excess profits allow monopolistic competitors to advertise in an attempt to further differentiate their products. More will be said about advertising, below, under Oligopoly.

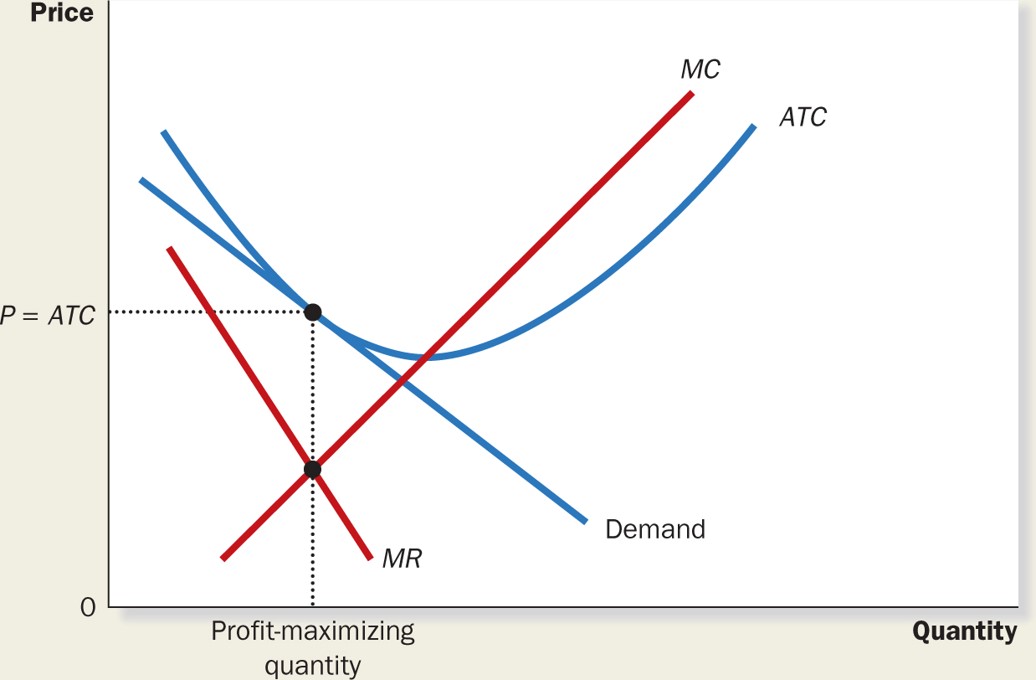

4. LR 4. Long Equilibrium (MKM C16/355-6; 334-6; 359-361; 335-337) In the long-run, however, excess or economic profits attract entrants. When a new entrant arrives in effect the niche demand curve is split between two producers. Some consumer prefer the original; some the new. The demand curve for original firm shifts to the left. As long as excess profits exist new entrants will arrive and the originating firm's demand curve will continue to shift to the left until it is tangent (just touching) the average total cost curve (ATC). Excess profits are eliminated and there is no incentive to enter. Long-run equilibrium is established where price (P) is equal to average total cost (ATC) and only normal profit is earned yet price is higher, quantity is lower and there is a deadweight loss of consumer & producer surplus compared to Perfect Competition (P&B 4th Ed. Fig. 14.2; 5th Ed. Fig. 13.2; 7th Ed Fig. 14.1 & Fig. 14.3; R&L 13th Ed Fig. 11-2; MKM Fig's 16.2 a & 16.3). The question arises: Are these costs and allocative inefficiencies justified by satisfying the differentiated tastes of consumers?

5.4 Oligopoly (MKM C17/371-88; 348-65; 373-392; 348-365)

i - Anonymity Like Monopolistic Competition the goods & services offered by producers under Oligopoly are seen by consumers as different from one another. There is product differentiation. Furthermore, a small number of large firms dominate the industry surrounded by a competitive fringe of smaller firms. Think the automobile industry in which the majors -Toyota, Ford, GM, Volkswagen, etc. - compete with niche players like Alpha Romeo, Austin Martin, Ferrari, Smartcar and Telsa. The level of dominance by the majors is measured by a concentration ratio reporting what percentage of industry output is contributed by the largest 3, 4, 5... producers . Most importantly, the actions of any major player is perceptible to rivals, i.e. there is interdependency of sellers whereby action of one results in reaction of others. ii - No Market Power A few large dominant firms contributing a significant part of market supply combined with product differentiation gives such firms significant market power. That some consumers prefer the goods & services of one major over another means the market demand curve is, in effect, disaggregated into distinct market shares. Some people will buy only Cheer while others will only buy Tide. In effect, such committed consumers are the most important asset of oligopolistic firms. They guarantee it remains a 'going concern' with customers coming back again and again. iii -Perfect Knowledge

As will be seen, under

iv -

Free Entry & Exit Given large firms often enjoy economies of scale and/or network economies together with product differentiation there can be significant barriers to entry in oligopolistic industries. Resulting excess profits permit oligopolists to indulge in non-price competition including extensive advertising, product & process innovation (R&D) and anti-competitive legal tactics, as will be seen below.

2. Solutions It is with Oligopoly that the geometric precision of the Standard Model of Market Economics breaks down. It does so because of the interdependence of the players. Under Perfect Competition, Monopoly and Monopolistic Competition it is the choices made by firms that determine a precise quantity/price profit maximizing outcome. In Oligopoly it is the reaction of rivals that makes a profit maximizing choice much more difficult. For example, Ford, to maximize profits, decides to offer zero percent APR financing of its cars. APR refers to 'Above Prime Rate'. The prime rate of interest is what the big banks charge their best customers. The next day Toyota follows suit effectively nullifying Ford's efforts. This is what I call 'the dance of the oligopolistis'. Many solutions have been proposed by economists but only two will concern us: the Cournot/Nash Solution and the Sweezy Kinked Demand Curve. i - Cournot/Nash Solution (MKM C17/373-5; 351-2; 376-377; 351-352) The Cournot Solution proposes that firms choose an output that will maximize profits assuming the output of rivals is fixed. The solution concludes that there is a determinant and stable price-quantity equilibrium that varies according to the number of sellers. In effect each firm makes assumptions about its rival's output that are tested in the market. Adjustment or reaction follows reaction until each firm successfully guesses the correct output of its rivals. A more sophisticated and complex solution known as the 'Nash-Cournot' equilibrium was proposed by John Forbes Nash, the protagonist of the movie 'A Beautiful Mind'. It involves long and complex calculations all of which depend on correct assumptions about actions/reactions. Change one assumption and the solution changes.

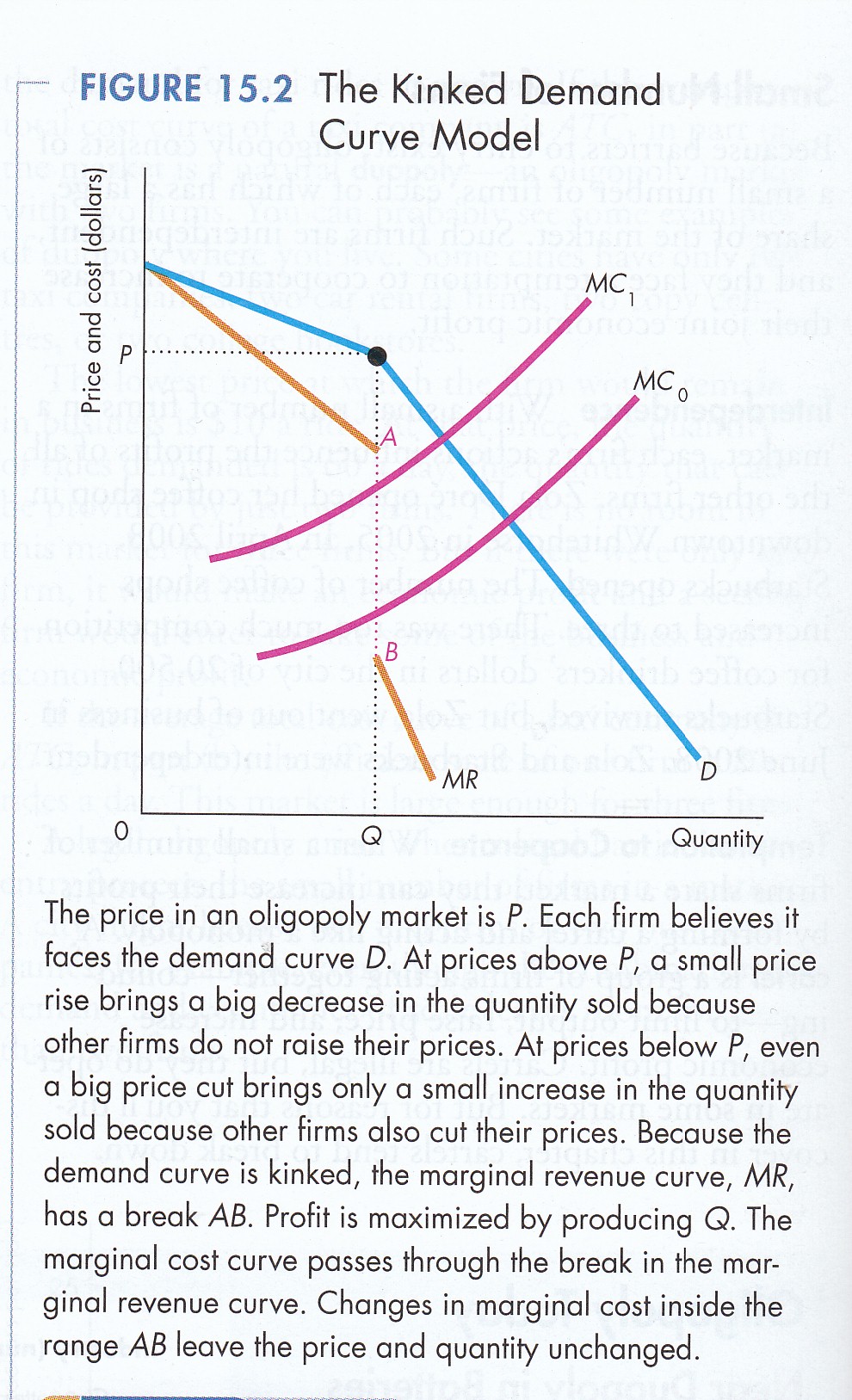

ii - Sweezy's Kinked Demand Curve Solution The Sweezy solution postulates that oligopolists face two subjectively determined demand curves that assume: rivals will maintain their prices; and, rivals will exactly match any price change. A key assumption is that rivals will choose the alternative least favorably to the initiator. If initiator raises its price, rivals will not follow; if it lowers price everyone follows. The result is that price will be relative rigid or sticky (P&B 4th Ed. Fig. 14.6; 5th Ed. Fig. 13.6; 7th Ed Fig. 15.2). This implies that oligopolists tend not to compete by price.

c) Non-Price Competition If oligopolist do not compete by price then how do the compete? There are at least 6 alternative patterns of industrial conduct: (i) Collusion (MKM C17/373; 351, 376; 351) Collusive behaviour among sellers as well as buyers especially in oligopolistic and oligopsonistic industries is historically and at present common practice. The small number of majors makes collusion relatively easy: “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.” Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1776 Collusion includes price fixing which involves agreement to buy or sell a good only at a fixed price and to manipulate supply and/or demand to maintain that price. The result of such cartels approximates the outcome of monopoly. It also includes agreements to geographically divide up markets. Maintaining discipline among members of the cartel is, however, often difficult because of the incentive to cheat. It should be noted that imperfect knowledge is involved. Cartel members know prices are fixed but the public does not. A recent example of such collusive behaviour occurred in 2012 with the rate rigging scandal concerning the Libor, the London Interbank Offer Rate. Some fifteen blue-chip banks ‘guess’ their borrowing costs, throw out high and low, and use the resulting rate as the benchmark against which to mark up riskier loans. These firms have already been fined billions of dollars for manipulation of the Libor rate. Such behaviour has recently, included price fixing of integrated chips, dynamic random access memory (DRAM) chips, liquid crystal display panels, lysine, citric acid, graphite electrodes, bulk vitamins, perfume as well as airlines in various countries around the world. The result of collusive industrial behaviour has been the institutionalization of government anti-trust and anti-combines policies around the world beginning in the United States with the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890. (ii) Game Playing (MKM C17/376-8; 353-6; 379-382; 353-359) A profit maximizing price/quantity solution for oligopoly cannot be found within the Standard Model of Market Economics. To treat the indeterminacy of oligopoly, economists, beginning with Cournot in the 1830s, have struggled for a solution. The outcome, however, depends not only on the decisions of a given firm but also the reaction of its competitors. To get around the problem Cournot suggested a firm should guess what competitors would do. If it guessed correctly it would maximize profits; if not, then it would guess again and again until it guessed right. Hardly an elegant solution! What I call the dance of the oligopolists with one step being matched by a counter-move also led in the 1950s to the Nash-Cournot solution which involves page upon page of mathematical equations (the Nash Program) that generates a solution if the underlying assumptions are correct. If not, the search for a solution also begins again. The ‘action-reaction’ nature and the complexity of oligopoly with a variety of possible ‘profit maximizing’ outcomes led economics to ‘spin off’ a whole new sub-field called Game Theory. For a brief history of Game Theory please see: An Outline of the History of Game Theory by Paul Walker Today it is claimed that video games, as an industry, is larger than the motion picture and music industries combined. Apps for smart phones are being designed around game theory to encourage everything from weight loss and exercise to saving. Modern corporations and the military actively engage in game playing including role playing to anticipate outcomes of competition, bargaining and other actions. Even the Arts are involved in that actors are often hired by businesses, governments, medicine, the military and other institutions to ‘role play’ in games to hone the skills of personnel. For example, actors are used to prepare physicians for the range of possible reactions of a patient being told they have terminal cancer. In many ways the contemporary ethos or zeitgeist is game playing. This sentiment is summed up in the neologism ‘gamification’. This has resulted from economic game theory developed in response to the indeterminancy of oligopoly. Legal tactics includes litigation or the threat of litigation, rather than the market, to settle or foreclose disputes with consumers, suppliers and competitors, e.g., the EULA software agreement that limits liability, e.g., downtime suffered by users. Legal tactics embrace contract law, non-contractual liabilities or the law of torts as well as intellectual property rights and property rights in general. Over the last few decades State-sponsored intellectual property rights or IPRs have increasingly become a tool of predatory competition as opposed to an incentive for innovation. It has been claimed that major American corporations now spend more on the legal defense of IPRs than on research & development. The many cases filed by Apple against Samsung in courts around the world is only the tip of the iceberg. For those interested, please see the following examples: Pricing strategy includes the choice between short- or long-run profit maximization as well as between single and tied goods, e.g., selling printers cheap but ink at a high price. Strict price competition, however, is restricted to perfect competition. Under imperfect competition firms are price makers rather than price takers. Another example of pricing policy concerns Microsoft Windows 95 to XP. Initially there was no online authentication required, only a product code on the disc cover. This meant it was easy to pirate but led to an ever widening group of users who became path dependent. Once online authentication was introduced owners of pirated copies were effectively compelled to buy Windows 2000 and subsequent editions to preserve their accumulated work. Pirated use of previous versions also increased the 'network economies' enjoyed by Windows. More recently zero monetary pricing to consumers for many 'apps' like Google Search & Maps, Facebook, et al, hides payment in the form of personal information that can be monetized through advertising revenue. Psychographic profiles of consumers and voters are but two outputs from data mining social media where consumers willingly provide new knowledge, online, with a click. Concern about the protection of such personal information has become a geopolitical issue particularly in the European Union. In fact, a new knowledge component has been added for which the OECD’s 1996 The Knowledge-Based Economy could not take account – Social Media and Big Data. Accordingly, it could not foresee protection of personal information becoming a geopolitical issue. The scale of the problem is highlighted in Jacob Weisberg’s “They’ve Got You, Wherever You Are”, New York Review of Books, October 27, 2016 where he notes: Facebook’s vast trove of voluntarily surrendered personal information would allow it to resell segmented attention with unparalleled specificity, enabling marketers to target not just the location and demographic characteristics of its users, but practically any conceivable taste, interest, or affinity. And with ad products displayed on smartphones, Facebook has ensured that targeted advertising travels with its users everywhere. For those interested in these issues, please see my 2016 essay: Disruptive Solutions to Problems associated with the Global Knowledge-Based/Digital Economy. Beyond questions raised in the essay such zero pricing causes significant problems in measuring Gross Domestic Product (GDP). If a good is not sold in a market with a price attached it simply is not counted. Yet how much is Google Maps worth to the lives of billions? Advertising is intended to persuade consumers – final or intermediary – to buy a particular brand. Sometimes brands are technically similarly but advertising can differentiate them in the minds of consumers, e.g., Tide vs. Cheer, effectively splitting off part of the industry demand curve as its ‘owned’ share. In the Standard Model of Market Economics only factual product information qualifies as a legitimate expense. Attempting to ‘persuade’ or influence consumer taste is ‘allocatively inefficient’ betraying the principle of ‘consumer sovereignty’, i.e., human wants, needs and desires are the roots of the economic process. This mainstream view connects with consumer behaviour research which calls this approach the ‘information processing’ model. A consumer has a problem, a producer has the solution and the advertiser brings them together. It is a calculatory process. An alternative consumer behavior school of thought, ‘hedonics’ argues that people buy products to fulfill fantasy, e.g., people do not buy a Rolls Royce for transportation but rather to fulfill a lifestyle self-image (Holbrook & Hirschman 1982; Holbrook 1987). Thus product placement, i.e., placing a product in a socially desirable context, enhances sales (McCracken 1988). In this regard the proximity of Broadway and especially off- and off-off-Broadway (the centre of live theatre) and Madison Ave. (the centre of the advertising world) in New York City is no coincidence. Marketeers search the artistic imagination for the latest ‘cool thing’, ‘style’, ‘wave’, etc. Such pattern recognition is embodied in the new professional ‘cool hunter’ (Gibson 2003). In fact peer-to-peer brand approval is consumer business success in the age of Blog. It should be noted that Alfred Marshall recognized the role of 'fancy': "Increasingly wealth is enabling people to buy things of all kinds to suit the fancy, with but a secondary regard to their powers of wearing; so that in all kinds of clothing and furniture it is every day more true that it is the pattern which sells the things." (Marshall 1920: 177-178). Take the case of advertising biotechnology. The ‘advertising & marketing’ of GM products, specifically food vs. medicine, highlights these divergent approaches. In reaching out to the final consumer GM food advertising and marketing generally takes the form of well researched and well meaning ‘risk assessments’. Such cost-benefit analyses are presented to a public that generally finds calculatory rationalism distasteful and the concept of probability unintelligible, e.g., everyone knows the odds of winning the lottery yet people keep on buying tickets. It would appear that the chances of winning are over-rated. By contrast the even lower probability of losing the GM ‘cancer’ sweepstakes are similarly over-rated. Attempts have been made to place this question within the context of known/unknown contingencies such as GM food safety within Kuhn’s ‘normal science’ (Khatchatourians 2002). The labeling debate also illustrates the ‘information processing’ view. At a minimum it would require all GM food products to be labeled as such. At a maximum it would require that all GM food products be traceable back to the actual field from which they grew. While attempts have been made to highlight the health and safety of GM foods little has been done to demonstrate that they ‘taste’ better. This may be the final hurdle, maybe not. Observers have noted, however, that the GM agrifood industry has been rather inept in its ‘communication’ with the general public (Katz 2001). For whatever reasons, to this point in the industry’s development, GM foods appear to feed nightmares, a.k.a., Frankenfood, not pleasant fantasies in the mind of the final consumer. By contrast the ‘advertising & marketing’ of medical GM products and services has fed the fantasies of millions with the hope for cures to previously untreatable diseases and the extension of life itself. Failed experiments do not diminish these hopes. Even religious reservations appear more about tactics, e.g., the use of embryonic or adult stem cells, rather than the strategy of using stem cells to cure disease and extend life. A contrast can be drawn between consumer resistance to GMO foods and Veblen goods, i.e., conspicuous consumption goods. Given that intermediate rather than final demand currently feeds the biotechnology sector one must also consider what might be called ‘intermediate advertising & marketing’. Such activities are conducted by trade associations and lobbyists. The audience is not the consumer but rather decision makers in other industries and in government. Such associations exist at both the national, e.g., BIOTECanada, and regional level, e.g., Ag.West Bio Inc. A firm may also indulge in both vertical and horizontal product differentiation. Vertical differentiation involves designing a product to be sold at very levels of consumer income. The classic example is Josiah Wedgewood in the late 18th century who used the same molds to make dinner settings for the royal court, aristocracy and the gentry by minimizing decoration as he moved down market. Horizontal differentiation involves, for example, offering the same product but in different colours. Another technique to achieve product differentiation in the minds of consumers is ‘design’. Apple is the outstanding example today. In effect design technology involves making the best looking thing that works. Picture going into a computer store and seeing two technically identical systems, one is ugly, the other attractive. Which do you buy? Economist Robert H. Frank’s economic guidebook unlocks everyday design enigmas. An explanation of his findings is available on a YouTube a lecture at Google HQ. What is important to realize is that product differentiation through advertising or design require an investment that a lean, mean perfectly competitive firm cannot afford. It is excess or economic profit that allows a firm to make such investments. Education in art stands on a somewhat different footing from education in hard thinking: for while the latter nearly always strengthens the character, the former not infrequently fails to do this. Nevertheless the development of the artistic faculties of the people is in itself an aim of the very highest importance, and is becoming a chief factor of industrial efficiency . . .. Increasingly wealth is enabling people to buy things of all kinds to suit the fancy, with but a secondary regard to their powers of wearing; so that in all kinds of clothing and furniture it is every day more true that it is the pattern which sells the things. (Marshall, 1920, pp. 177-178) (vi) Process/Product Innovation With respect to process/product innovation I begin with a distinction between invention and innovation. Invention involves creating something new; innovation involves successfully bringing it to market. To paraphrase Einstein: it is 1% inspiration (invention) and 99% perspiration (innovation). Process/product innovation forms part of what economist Joseph Alesoph Schumpeter called creative destruction or the: … process of industrial mutation - if I may use that biological term - … that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new … Creative destruction is the essential fact about capitalism. It is what capitalism consists in and what every capitalist concern has got to live in. Every piece of business strategy acquires its true significance only against the background of … the perennial gale of creative destruction; it cannot be understood irrespective of it or, in fact, on the hypothesis that there is a perennial lull. (pp. 83-84) From this observation, and other evidence, Schumpeter concluded that the Standard Model of Market Economics missed the point. Competition was not about long run lowest average cost per unit output but rather about innovation and surviving the perennial gale of creative destruction. For those interested, please see Observation #9: Economic Concepts of Technological Change. In oligopoly the excess profits earned, relative to normal profit of a competitive firm, are used to finance all forms of non-price competition. In the orthodoxy this results in smaller output, higher prices, a deadweight losss of exchange surplus and appropriation of consumer surplus as monopoly profits. The objective of the Standard Model is the lowest long-run average cost per unit. Does observation of the real world support pursuit of this objective?

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||