Microeconomics

Macroeconomics

SISTERetrics

SITES

Compleat World Copyright Website

World Cultural Intelligence Network

Dr. Harry Hillman Chartrand, PhD

Cultural Economist & Publisher

©

h.h.chartrand@compilerpress.ca

215 Lake Crescent

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan

Canada,

S7H 3A1

Launched 1998

|

Microeconomics 5.0 Competition (cont'd)

|

|

If any of the four strict assumption

for perfect competition do not hold then imperfect competition

exists. Under imperfect competition one or more buyers or sellers

have a perceptible influence on the price/quantity outcome.

The form of imperfect competition is determined by the number of

buyers or sellers with such influence:

monopoly/monopsony (single seller/single

buyer)

duopoloy/duopsony

oligopoly/oligopsony monopolistic competition (many sellers of differentiated goods & services). We will examine monopoly, monopolistic competition and oligopoly by changing the assumptions of perfect competition and determine their short and long run equilibrium and compare it with perfect competition. Beginning with monopoly: i - Anonymity Under Monopoly while goods & services are homogenous there is only one seller and hence no anonymity. Everyone knows the monopolist. ii - No Market Power Under Monopoly there is only one seller facing the market demand curve and that seller has market power to be a 'price maker', i.e., it can choose profit maximizing output. Market power is limited only by the proximity of substitutes. The degree of market power is reflected by the elasticity of the market demand curve. The more inelastic the demand curve, the more market power; the more elastic, the less market power. The market supply curve is the marginal cost curve of the monopolist above the shut down point. iii -Perfect Knowledge

iv -

Free Entry & Exit

2. Marginal Revenue Curve

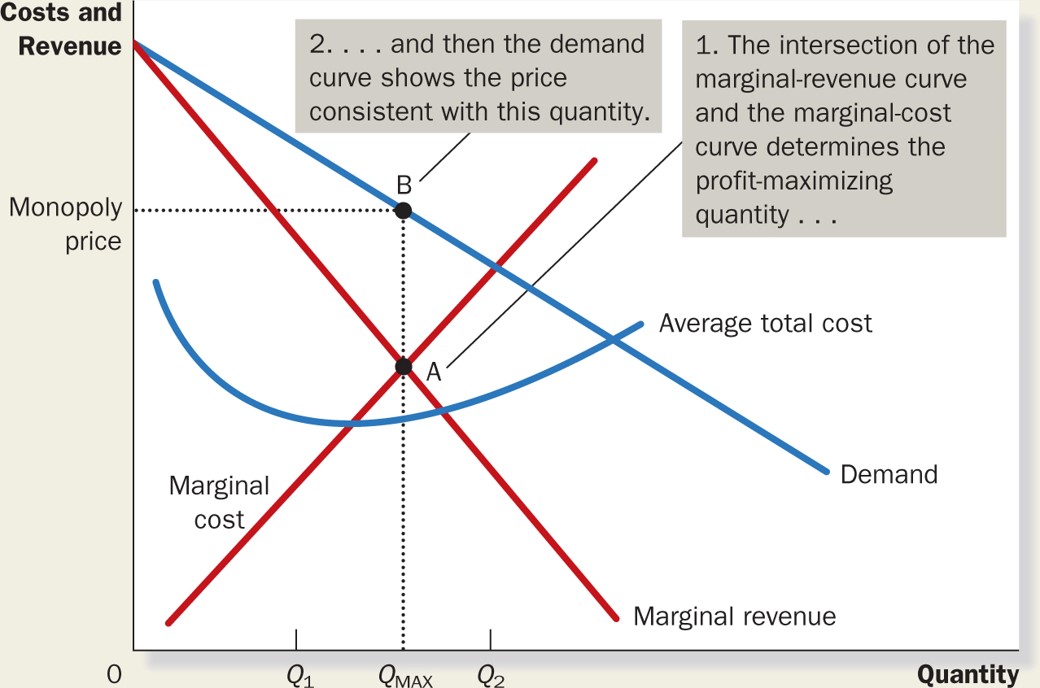

The market supply curve is the horizontal summation of the MC curves (above shut down) of all producers in an industry. In perfect competition entry or exit of a firm shifts the market supply curve. In Monopoly, however, there is only one producer - the monopolist. The market supply curve is, in fact, the monopolist's MC curve above its shut down point. MKM Fig. 15.4

3.

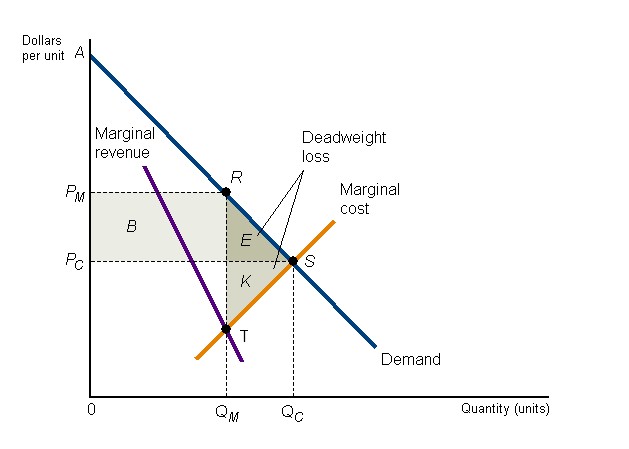

Short-Run Equilibrium The second cost is a price of Pm rather than PC, i.e., higher price.

The third cost is allocative efficiency. If the monopolist supplied Qc then consumer surplus would include the triangle E (consumer surplus every thing up from price to the demand curve). Similarly, producer surplus would include triangle K (producer surplus everything from price down to the supply curve). However, because the monopolist produces at Qm rather than Qc both consumer surplus E and producer surplus K are not generated. They are lost - triangle RST. This is called the deadweight loss of monopoly. In other words, the monopolist does not allocate enough capital, labour and natural resources to produce the competitive outcome, Qc. Monopoly displays allocative inefficiency. The fourth cost of monopoly involves the appropriation of consumer surplus in the form of monopoly profit (rectangle B). Why are consumers willing to pay a higher price for a smaller quantity? The law of diminishing marginal utility.

d) Long-Run Equilibrium f) Monopoly & ‘Big” in Economic Thought The exercise of market power is not limited to true monopolies. As will be seen other imperfect forms of competition can exercise similar influence of the quantity/price outcome. This raises the issue of whether simply being 'big' as in big corporations including the banks is the problem. In the United States the current question of the corporate personality asks whether Legal Persons, i.e., bodies corporate including government and corporations, enjoy the same rights as Natural Persons, i.e., flesh & blood human beings. For those interested in the question, please see: Observation #8: Monopoly & 'Big' in Economic Thought. 'Big' can also mean spread across industries as 'conglomerates'. The first wave in the US occurred in the later 1960s and continued through the early 1980. A large firm would buy up smaller firms in different industries based on the premise that management was the ultimate input. If you could manage an airline you could manage a chocolate factory and so on and so on. A second wave is occurring today in High Tech. For example, see "The Tech Monsters": https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/the-tech-monsters .

|