What I call the Standard Model of Market

Economics did not just appear. Rather it evolved over some 70 years

between the 1870s and 1940s. For those interested in its evolution,

please see Observation #1: Origins. The model employs many

concepts (from the Latin: to grasp firmly with the hand). To introduce its construction, operation and critique, I

present, in brief, some of the most critical. These are the 'tools

of the mind' we will use through out the course.

1.

Scarcity, Choice &

Opportunity Cost (MKM C1/4–6:

2-4;

2-4;

2-4)

Without Scarcity there would be no Economics. Scarcity is that

permanent human condition in which our wants, needs and desires always

and forever will exceed the means available to satisfy them.

Mainstream economics does not differentiate between wants,

needs and desires. As will be seen this is similar to mainstream

economics treatment of different kinds of knowledge. Wants, needs and desires,

however, can be defined using

Maslow's

Need Hierarchy.

Accordingly, we must choose between alternative ways of maximizing our

satisfaction. Economics has in fact been called the science of choice.

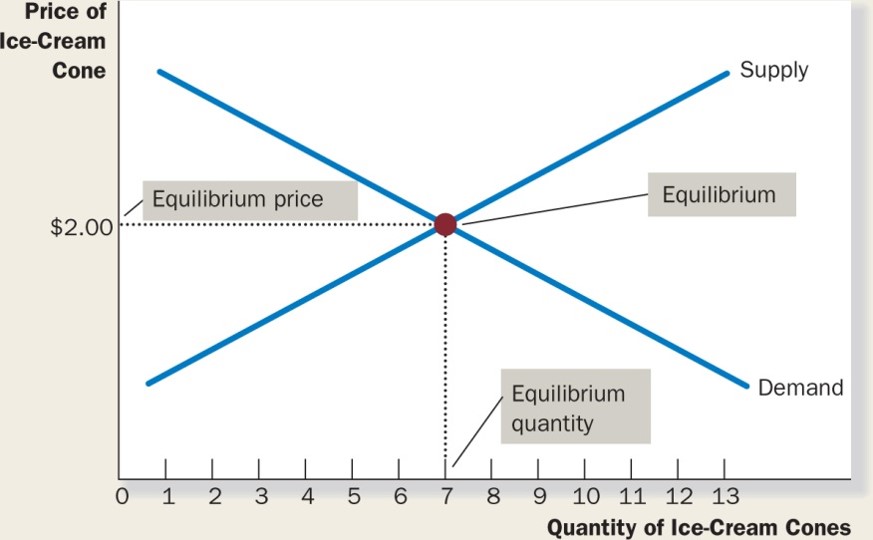

In choosing one alternative over all other alternatives we give up the

next best alternative. This is the opportunity cost of choice –

the next best alternative forgone. In

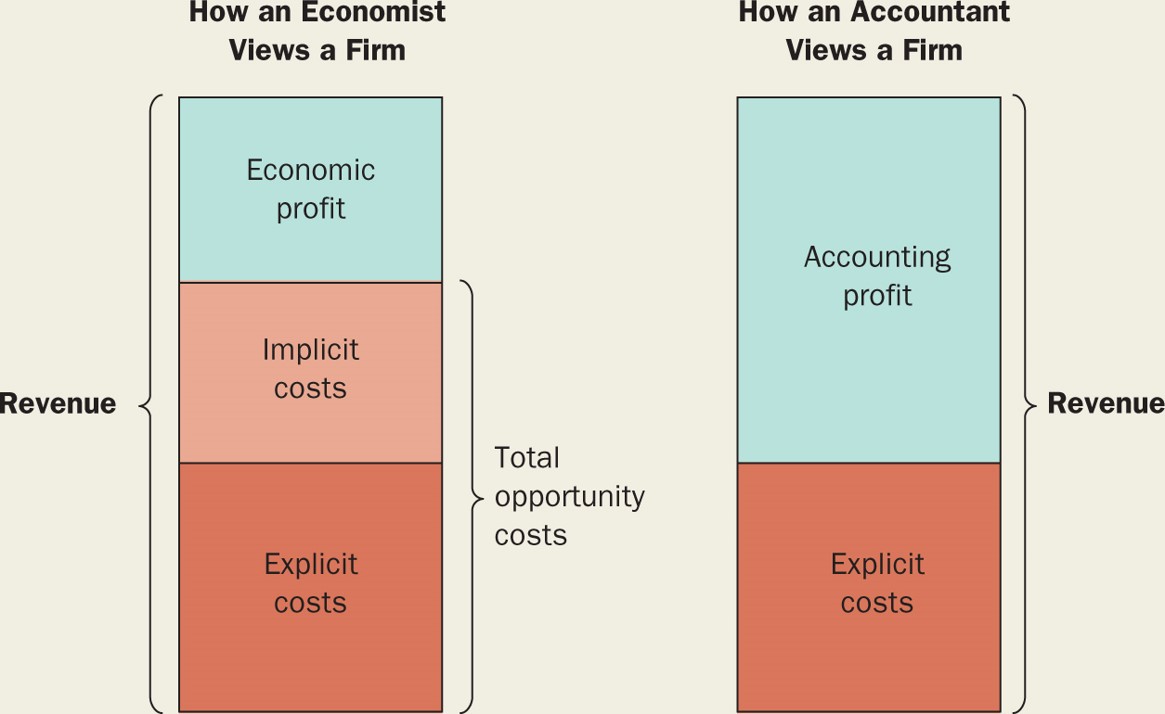

Economics all costs are opportunity costs. This concept distinguishes

Economics from accounting, business and commerce

(MKM Figure 13.1):

Quite simply, without Scarcity there is no need for Economics, no need

to choose. You can have everything! Scarcity is the prime

directive of Economics.

In

Microeconomics, it involves allocation of scarce resources by consumers

and producers; in Macroeconomics, allocation of scarce resources by

market price and the State.

Market price measured in dollars, euros, pounds,

renminbi, yen, etc., are useful but do not necessarily reflect

the 'real cost' of a good or service. Take the opportunity cost of work. If one works an hourly job, one is paid a wage

per hour that multiplied by hours worked equals income, e.g., 4

hours @ $10 an hour equals $40 of income. This does not, however, allow for

the opportunity cost associated with preparing for, then re-creating after, work

including commuting both ways, e.g., 2 hours. The real wage per hour

is now $40 of income divided by 6 not 4 hours or $6.67 per hour.

We can also determine opportunity cost

by calculating the 'relative price' of a good or service. Relative

price is the ratio of one price to another. For example, if the price of a

Coke is $1.00 and chewing gum $0.50 the relative price of Coke is

$1.00/$0.50 or 2, i.e. you could buy 2 packs of chewing gum for the price

of one Coke.

There

are, of course, thousands if not millions of different goods and services all with

different and changing market prices. Accordingly, relative price is usually expressed

as the price of a standard basket of goods and services measured

using a price index.

Let us say overtime we observe the same basket of goods and

services cost $100 in 2001 but $110 in 2011. In this case, we divide the monetary price

in 2011 by the price in 2001 finding the price went up 10%.

Such a basket of goods & services represents a measure of our well

being. Relative to 2011 this means we need to earn 10% more income to maintain our

standard of living. The currency has suffered inflation - the same

number of dollars buys less than before. By contrast, if the price

change reversed, $110 in 2001 but $100 in 2011 then the currency has

deflated - less buys more.

In

microeconomics, price means 'relative price' of specific goods &

services. Thus when the price of a good or service falls, we do not mean

its monetary price but rather that price relative to other goods and services, i.e. it's

opportunity cost falls. In macroeconomics concern focuses on the

aggregate price level of all goods & services within a

national economy. The question of international prices

is even more complicated. The income of a salaried executive

in Saskatoon supports a certain standard of living. To maintain

that standard in Hong Kong or London or New York or Singapore or Tokyo

how much would one's income have to increase?

One widely used measure of purchasing power parity is the 'Mac

Index' which measures the number of hours of work required to buy a 'Big Mac' in different

countries.

2.

Expectations/Futurity/Time

(MKM C4/73 & 78:

68 & 73;

70 & 75;

69)

Choice, however, involves more than here

and now. Time plays multiple roles in Economics. First, there

is static and dynamic analysis. Static involves a fixed moment in time;

dynamic involves analysis of Past to Present to Future.

Second,

John Maynard Keynes uses the term ‘expectations’. People’s changing

expectations of tomorrow alters their actions today. John R. Commons

uses the term ‘futurity’ meaning people live in the future but act in

the present. What we expect tomorrow determines what we do today.

Deferred gratification, i.e., waiting for tomorrow, is the source

of savings - deferred consumption.

Third,

there is the very short run, the short run and the long run. In the

very short run the quantity of all inputs (Capital, Labour and Natural

Resources) is fixed, so is output. In the short run at least one factor

of production is fixed (usually Capital), while others (usually Labour

and Natural Resources) are variable. In the long run all factors are

variable. These time periods are functional, not chronologic. The long

run for a new Tim Horton’s is 6 months to a year but 10 years or more

for a steel mill, hydro dam or nuclear power station.

3.

The Big ‘M’ & Constrained Maximization

(MKM C1/7-8: 4-6;

4-6;

4-6)

The question becomes: How to choose? Flip

a coin? Consult the spirits? Decision making in the Standard Model is

done at the ‘margin’. In daily conversation marginal means

unimportant. In Economics marginal defines the choice point. The

marginal unit is the last grain of sand tipping the balance. In

Newtonian calculus of motion the marginal is the derivative: first

derivative - the rate of change; second derivative - change in the rate

of change. The marginal concept defines economic choice in the Standard

Model. For example:

marginal utility: the additional

satisfaction of one more unit in consumption;

marginal product: the additional output of

one more unit input;

marginal cost: the additional cost of one

more unit output; and,

marginal revenue: the additional revenue

from sale of one more unit.

Examples in Macroeconomics include:

marginal propensity to consume: the part

of an additional dollar in income spent on consumption;

marginal propensity to save: the part of

an additional dollar in income retained as savings;

marginal propensity to import: the part of

an additional dollar in income spent on imported goods & services; and,

marginal tax rate: the part of an

additional dollar in income taken in taxes.

As will be seen economic choice involves

constrained maximization. Thus a consumer in striving to maximize

happiness is constrained by income and price. Similarly when a firms

strives to maximize profits it is constrained by existing technology,

input costs and the revenue earned for the output. All decisions

made at

'the margin'.

4.

Geometry, Calculus & Symbolic Equations

(MKM C2/39-47:

35-45;

36-47;

34-42)

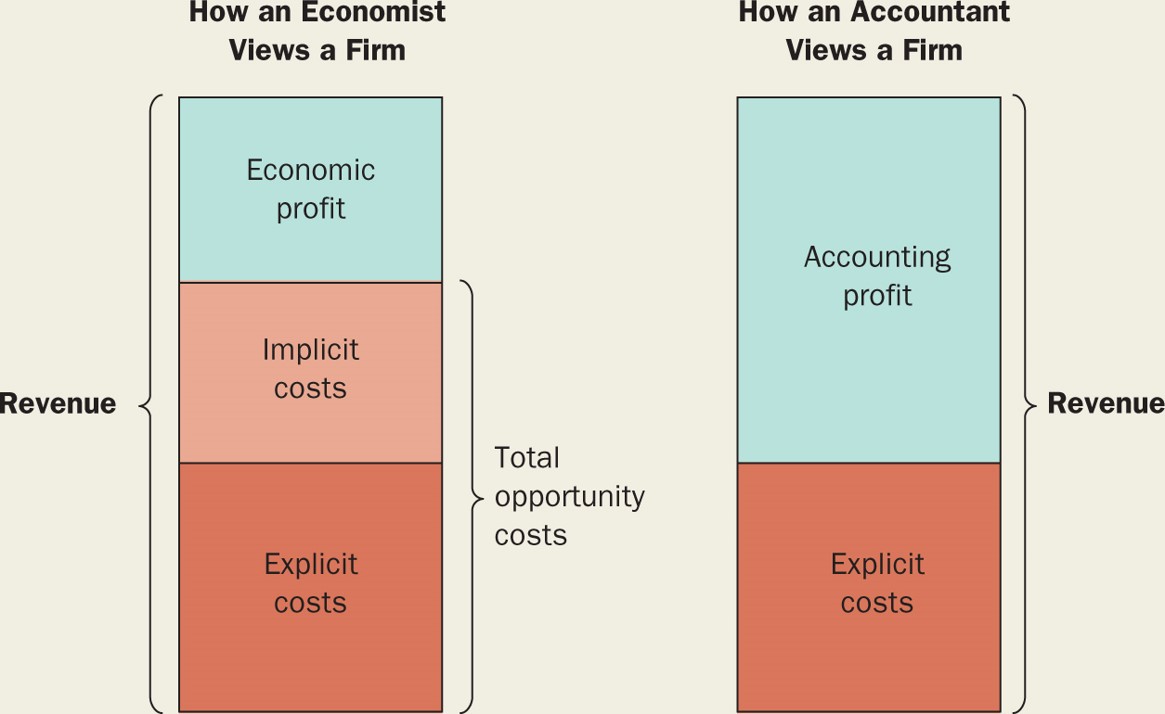

Geometry is the West’s unique contribution

to Mathematics. In the hands of Euclid, Archimedes and Ptolemy the

ancient Greeks used universal forms of the circle, square, triangle and

their variations, e.g., the parabola, to explain two- and

three-dimensional space including movement of the stars. Those

interested in further detail, please see

Observation #2: Geometry.

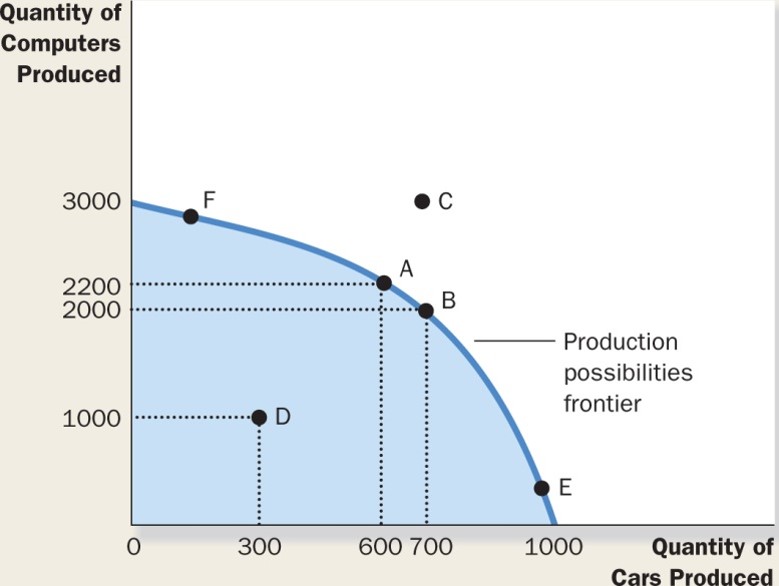

At the beginning of the European

Enlightenment & Scientific Revolution Rene Descartes (1596-1650) introduced analytic geometry

using a coordinated two-dimensional space defined by two axis: the

X-axis or abscissa and the Y-axis or ordinate defining the location of

every point, e.g., (600, 2200) a point 600 units to the right and

2200 units up. [MKM Fig. 2.2].

Analytic geometry has since been extended to

n-dimensional space. In this course you will make extensive

use of what Alfred Marshal, father of the Standard Model,

began developing in 1867: “diagrammatic economics”. Keynes, in

his 1924 obituary to Marshal, noted that “such diagrams must surely form

a part of every advanced course in economics, and they should be

available for students in the fullest and clearest form possible.” I

argue that what was true for ‘every advanced course’ in 1924 is true for

an introductory courses in 2020.

Analytic geometry has since been extended to

n-dimensional space. In this course you will make extensive

use of what Alfred Marshal, father of the Standard Model,

began developing in 1867: “diagrammatic economics”. Keynes, in

his 1924 obituary to Marshal, noted that “such diagrams must surely form

a part of every advanced course in economics, and they should be

available for students in the fullest and clearest form possible.” I

argue that what was true for ‘every advanced course’ in 1924 is true for

an introductory courses in 2020.

In the 1670s, what was known as ‘the

geometry of infinitesimals’, i.e., geometric exhaustion, achieved

a breakthrough with the independent invention of the calculus by Newton

(1643-1727) and Leibniz (1646-1716). Calculus provided a true

mathematics of motion – changing spatial position through Time expressed

in algebraic rather than geometric terms. No calculus will be used in

this course.

Finally, a symbolic equation is a

generalized statement of a functional relationship between a dependent

and independent variables. No numbers or the nature of the functional

relation is stated. Examples in the Standard Model include:

The Consumption Function expressed as:

U = f (x, y) where:

U (dependent variable) is the utility or

satisfaction derived from consuming commodity combinations of x and y

(independent variables); and,

f

is the taste or preference function of the

consumer; and,

The Production Function of the firm

expressed as:

Q = g (K, L, N) where:

Q (dependent variable) is the output;

independent variables include:

K is Capital plant & equipment;

L is Labour; and,

N is Natural Resources.

g is technology or ‘know-how’;

Throughout the course these and other

symbolic equations will be displayed in Cartesian space defined by X-

and Y-axes coordinates.

5.

Demand, Supply & Markets

(MKM C4/67-88: 62-82;

65-86;

58-84)

Demand, Supply & Markets are the high

order concepts in both Micro and Macroeconomics. In Microeconomics it

is demand for and supply of a specific good or service. Demand reflects

the constrained maximization of happiness by a consumer faced with a

limited budget, prices and the need for other goods & services. Supply

reflects the constrained maximization of profit by a firm faced with

existing technology, input costs and revenue per unit. In

Macroeconomics it is Aggregate Demand for and Aggregate Supply of all

goods & services in a national economy. For purposes of introduction I

restrict myself to Microeconomics. The concepts, however, apply in

Macro.

i - Demand

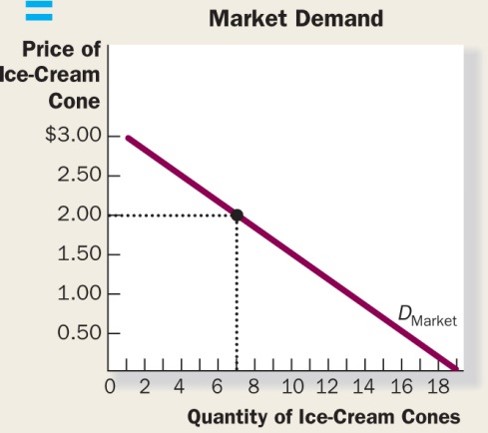

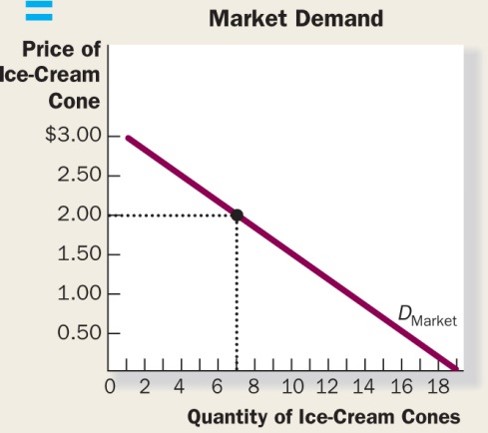

All other things being equal, the higher

the price the lower the demand; the lower the price the higher the

demand. This is the Law of Demand. The Demand Curve [MKM Fig 4.2]

shows the relationship between price and

quantity demanded of a good or service. It shows a consumer’s

willingness to pay different prices for different quantities of a good

or service. All things being equal, the Demand Curve is downward

sloping reflecting the Law of Demand.

shows the relationship between price and

quantity demanded of a good or service. It shows a consumer’s

willingness to pay different prices for different quantities of a good

or service. All things being equal, the Demand Curve is downward

sloping reflecting the Law of Demand.

Assuming the taste of consumers, the price

of other goods & services as well as income remain constant there will

be movement up and down along the curve as price changes. If any of the

constants change, however, the Demand Curve will shift [MKM Fig. 4.4 a &

b]. In Cartesian space adding horizontally how much each

consumer is willing to buy at each price generates the Market Demand

Curve. The Market Demand Curve is thus an aggregation of individual

consumer demand curves. As will be seen, and importantly, what can

be aggregated can sometimes be disaggregated.

ii - Supply

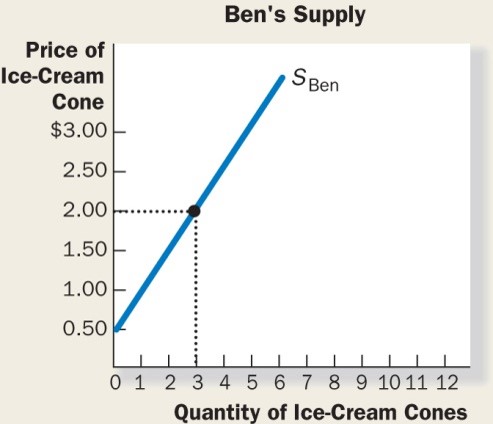

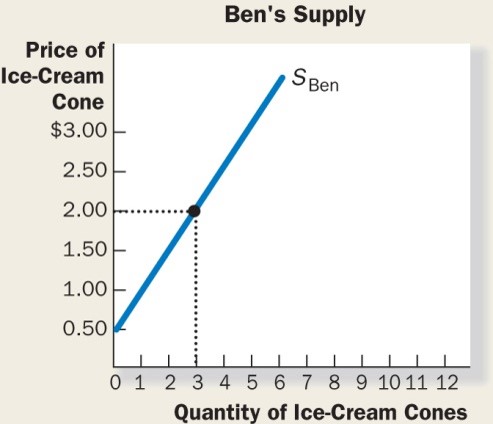

All other things being equal, the higher

the price of a good or service, the higher the quantity supplied; the

lower the price, the lower the supply. This is the Law of Supply. The

Supply Curve [MKM Fig 4.6]

shows the relationship between price and

quantity supplied. It shows the willingness of a producer to sell. All

things being equal, the Supply Curve is upward sloping reflecting the

Law of Supply. Assuming the cost of inputs and technology remain

constant, there will be movement up and down along the curve as price

changes. If any of the constants change, however, the Supply Curve will

shift [MKM

C4/78, Fig 4.7]. In Cartesian space adding horizontally how

much each firm is willing to sell at each price generates the Market

Supply Curve. The Market Supply Curve is thus an aggregation of

individual firm supply curves. As will be seen, and importantly,

what can be aggregated can sometimes be disaggregated.

shows the relationship between price and

quantity supplied. It shows the willingness of a producer to sell. All

things being equal, the Supply Curve is upward sloping reflecting the

Law of Supply. Assuming the cost of inputs and technology remain

constant, there will be movement up and down along the curve as price

changes. If any of the constants change, however, the Supply Curve will

shift [MKM

C4/78, Fig 4.7]. In Cartesian space adding horizontally how

much each firm is willing to sell at each price generates the Market

Supply Curve. The Market Supply Curve is thus an aggregation of

individual firm supply curves. As will be seen, and importantly,

what can be aggregated can sometimes be disaggregated.

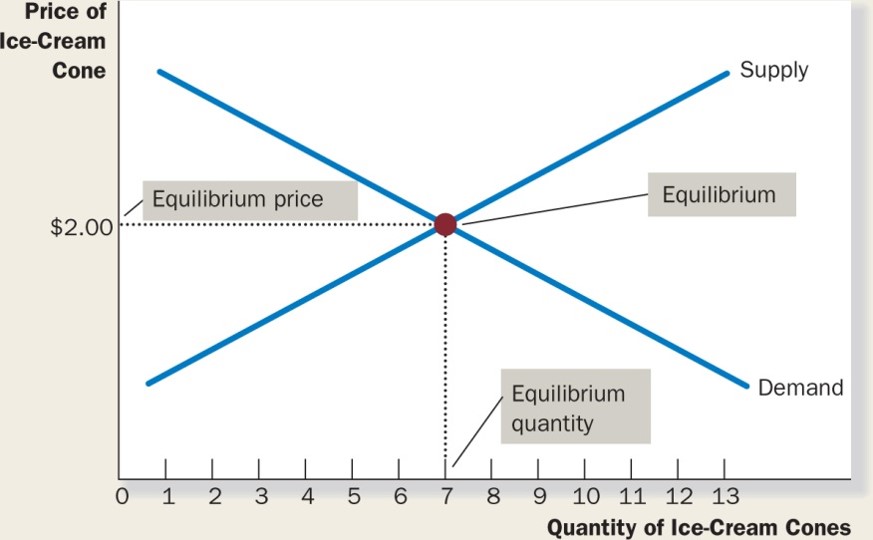

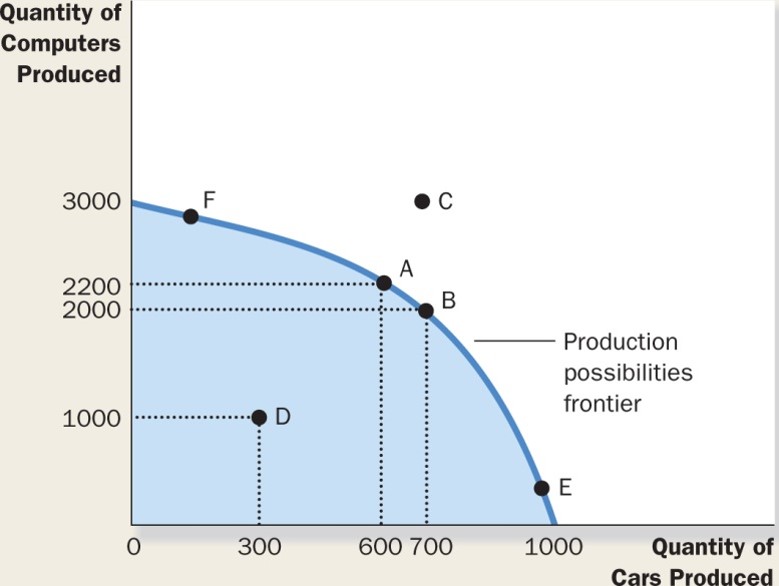

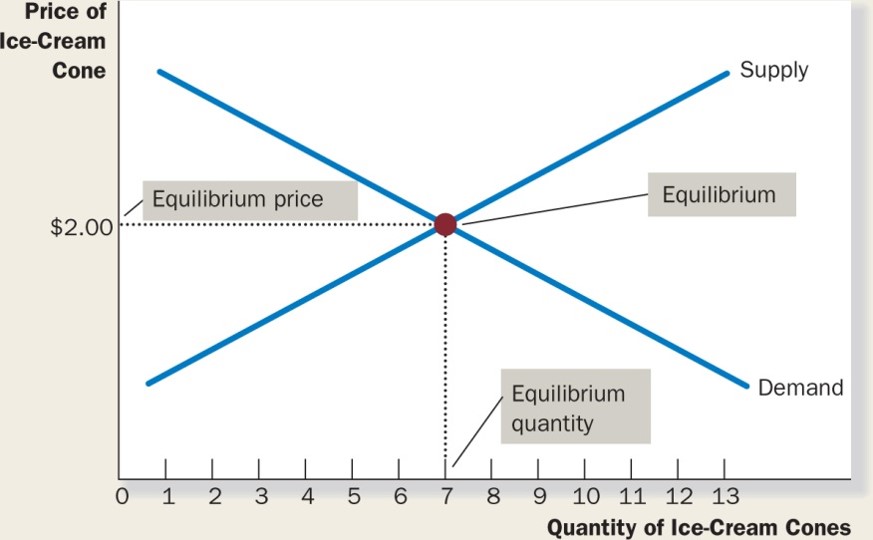

iii -Markets

Markets exist anywhere, in real or virtual

space, that buyers and sellers can transact business. Put another way,

Markets are where Demand meets Supply setting a price/quantity that

clears the market; ‘X’ marks the spot where the willingness to buy

exactly matches the willingness to sell [MKM Fig 4.8].  Markets can be:

Markets can be:

- commodity-based, geographic or virtual;

- in or out of equilibrium [MKM

Fig 4.9 a &

b];

- sensitive or insensitive to changes in

price, income, taste or technology;

- influenced by someone - consumer,

producer or government - altering the price/quantity outcome by

exercising market power.

In a Market, price regulates the quantity

of goods and services demanded and supplied. If price is too high,

consumers demand less than producers are willing to supply. A surplus

exists. To rid themselves of this surplus producers lower their price.

If price is too low, consumers demand more than producers are willing to

supply. A shortage exists. To get more of the good consumers bid up

the price [MKM Fig 4.9 a &

b]. The tendency of producers to lower price faced with

a surplus and consumers to bid up price faced with a shortage is called

Market Forces. These tend to keep the market price/quantity where ‘X’

marks the spot.

6. 10 'Es' of Economics

By coincidence many of the key concepts in

Economics begin with the letter ‘e’. Here are what I consider the top

10.

i -

Efficiency

(MKM C2/26-7:

23-24; 25-26;

22-23; C7/160: 149;

156;

141)

As will be seen efficiency has many

meanings in Economics including: allocative, consumer, economic,

exchange, producer and technical efficiency. In all cases, to

measure efficiency one must be able to quantify both inputs and outputs.

This is possible in the case of the resource and manufacturing

industries with physical inputs and outputs but not so much for the

service industries including government. In introduction consider

technical and economic efficiency. Technical efficiency is achieved

when it is not possible to increase output without increasing inputs.

Economic efficiency, on the other hand, occurs when the cost per unit

output is as low as possible. All economically efficient solutions are

technically efficient but not all technically efficient solutions are

economically efficient.

ii -

Effectiveness

For some goods and most services inputs

and/or outputs cannot be directly measured and hence technical and

economic efficiency cannot be calculated. Accordingly, a less stringent

test - cost effectiveness - is used. Surrogates or proxy indicators of

inputs and outputs are developed. Consider the criminal justice

system. How do we measure its inputs and outputs or its success? The

number of arrests? The number of convictions? The “recidivism rate”

measured as the percentage of repeat offenders? The related rate of

rehabilitation? Case load per parole officer? Or the more difficult to

measure opportunity cost of resources in alternative applications,

e.g., early education?

iii -

Elasticity

(MKM C5/97-117:

90-110;

97-117;

86-105)

Elasticity refers to the sensitivity of

one variable to a percentage change in another variable. As we will be

seen, in Economics there are many forms of elasticity including: income

& price elasticity of Demand, price elasticity of Supply and

cross-elasticity or the elasticity of substitution. In all cases there

are three types:

elastic

when a 1% change in one variable results in a greater than 1% change in

the other, e.g., a 1% increase in price results in a 5% decrease

in sales;

unitary

when a 1% change in one variable results in a 1% change in the other;

and,

inelastic

when a 1% change in one variable results in a less than 1% change in the

other, e.g., a 1% increase in price results in a 0.01% decrease

in sales.

iv -

Employment

In daily life employment is usually

associated with Labour. In Economics, however, all factors of

production including Capital and Natural Resources are subject to

over-employment, full-employment, under-employment and unemployment.

In the case of Capital, capacity

utilization measures employment of physical plant and equipment.

Generally, 85% capacity utilization is considered full employment of

Capital allowing for downtime and maintenance.

Similarly, employment or exploitation of

Natural Resources may be over, fully, under- or simply unemployed and

left in situ. Appropriate conservation methods are required to

determine the appropriate level of exploitation.

In the case of Labour, the Labour force is

defined as all persons between 15 and 65 years of age. The participation rate is the percentage of the

Labour force that has or is actively seeking employment [MKM Macro Fig. 9.3]. There are various types of unemployment

including:

frictional

exists when there is a job available for every worker who wants one but

some will always be between jobs, i.e., unemployed;

seasonal

characterizes industries like farming, fishing, forestry and skiing;

cyclical

follows the business cycle, up and down;

structural

reflects, among other things, the impact of technological change making

existing skills redundant, e.g., the Canadian Maritime provinces

were world leaders in sailing technology but the entire industry

disappeared with the shift from wood and sail to iron and steam late in

the 19th century; and,

the natural rate

of unemployment accounting for frictional, seasonal cyclical and

structural unemployment. The natural rate varies between countries due

to structural and policy factors such as unemployment insurance programs

[MKM Macro Fig. 9.4].

v -

Endogenous/Exogenous

Economic models like the Standard Model

are closed system. Within the system variables are endogenous, inside.

Variables outside the system are exogenous, e.g., changes in the

Law, political instability, civil unrests or calm. Some variables may

be both. Take technological change. In Economics technological change

refers to the impact of new knowledge on the production function of a

firm or nation.

Endogenous technological change emerges

from the pursuit of profit. Thus industrial research and development or

R&D includes minor modifications or tinkering with existing Capital

plant and products called ‘development’. R&D varies significantly

between firms and industries. At one extreme, a change may be

significant for an individual firm but trivial to the economy as a

whole. On the other hand, there are ‘enabling technologies’ such as

computers or biotechnology that influence all industries.

The source of exogenous technological

change is outside the economic process. New knowledge emerges, for

example, in response to the curiosity of inventors and pursuit of

‘knowledge-for-knowledge-sake’, i.e., pure research usually

conducted in universities. Exogenous change, with respect to a firm or

nation, falls like manna from heaven.

vi - Equilibrium

(MKM C4/79-85:

74-80;

76-82;

70-75)

Equilibrium is a condition once achieved

continues indefinitely. In Economics there are different types of

equilibrium but for our purposes only two need be considered

Stable Equilibrium:

refers to a condition which once achieved self-adjusts to any change

maintaining the equilibrium state - homeostasis. Changes causing a

shift out of equilibrium generate forces leading back to equilibrium.

Consider a ball resting at the bottom of a cup; shake it and the ball

moves; stop shaking and it returns to the bottom of the cup. As we will

see, in market equilibrium price/quantity ‘clears’ the market - the

quantity demanded exactly equals the quantity supplied. If price rises

above equilibrium supply exceeds demand - a surplus is created; if price

drops below equilibrium demand exceeds supply - a shortage. Market

forces then drive the system back to the equilibrium clearing the

market; and, [MKM

Figs. 4.8]

[MKM

Figs. 4.8]

Unstable Equilibrium:

refers to a condition which once achieved does not self-adjusts to

maintain the equilibrium state. Consider a ball resting on the top of

an overturned cup - shake it and the ball falls off never to return to

the same place.

vii - Equity

(MKM C1/5:3; C12/264-70:

247-253;

273-278;

253-258)

The economic concept of Equity evolved out

of a distinct strand of English legal history. Together with the Common

Law, Equity emerged during the reign of Henry II (1133 –1189). Those

interested in the legal origins of Equity, please see

Observation #

3: Equity.

The Common Law is concerned with right and

wrong, guilt or innocence. Equity is concerned with fairness. Economic

concepts of Equity derive from legal Equity. Thus the Chancellor of the

Exchequer (in Canada called ‘the Minister of Finance’) exercised

concurrent jurisdiction in Equity with the Lord Chancellor’s Court.

There are two economic definitions of

Equity, each reflecting its historical roots. First, there is Equity as

the financial capital of a limited liability corporation which, after

deducting liabilities to outsiders, belongs to the shareholders. Hence

shares in a limited liability corporation are known as equities. This

links back to the historical development of trusts under Equity.

Second, there is Equity as ‘fairness’.

While usually used with reference to taxation it is a general economic

concept. With respect to taxation Equity has three dimensions:

horizontal, vertical and overall. Horizontal Equity refers to ‘like

treatment of like’. Vertical refers to ‘unlike treatment of unlike’.

Overall Equity refers to the accumulated impact of all forms of

taxation. Crudely, it is the difference between earned and disposable

income, i.e., income net of all taxes – income, excise, sales,

et al. Equity is also used to justify market intervention by

Government, e.g., minimum wage and rent control.

It is important to distinguish between

equity and equality. Equity is about fairness, given the facts of

a situation. Equity is part, not just of law and economics, but

also of ethics, the science of morals. It is not biased in favour

or opposed to equal, egalitarian outcomes. Outcomes simply must be

fair. The difference between equal opportunity and equal outcomes

highlights, in a way, the difference between equity and equality.

In this regard, Kenneth Boulding entitled his

Presidential address to the 81st meeting of the American Economic

Association in Chicago, December 29, 1968:

Economics

as a Moral Science.

viii - Ethics/Moral

Sentiments

#8 of the Ten Humorous Reasons for

studying economics reads: Although ethics teaches that virtue is its own

reward, in economics we get taught that reward is its own virtue. This,

alas, from a now dark website: JokEc.

While self-interest or ‘Me-ism’ lays at

the heart of economics it is in fact qualified by moral considerations.

Thus while Adam Smith is remembered as the founder of modern economics

with the 1776 publication of his Inquiry into the Wealth of Nations

some 17 years earlier in 1759 he published The Theory of Moral

Sentiments (1759) providing the ethical, philosophical,

psychological, and methodological underpinnings of all his later

works.

Today such concerns are summed up as

‘market sentiments’. Such sentiments include, among other things,

trust. Overtime buyers and sellers, producers and suppliers, employers

and employees develop trust reducing what are called transactions

costs. Without such trust every exchange must be carefully and

expensively scrutinized to insure all terms of a contract are fulfilled

by both parties. In times of recession, such as now, relations tend to

break down with producers and/or their suppliers going out of business,

employees laid off, etc. Like a rug or woven sweater relations

unravel and if this last long enough new supplier or new employees must

be engaged who, at the beginning of the relationship at least, are

subject to uncertainty and a lack of trust raising transaction costs.

ix- Excludability

(MKM

C11/236:

221;

243; 224)

Private goods exhibit excludability and

rivalrousness. If I buy a car I exclude you by lock and key.

Similarly, if I am driving I exclude you, i.e., driving is

rivalrous. Public goods, on the other hand, are non-excludable and non-rivalrous,

i.e., it is hard to stop me from consuming and my consumption

does not reduce the amount available to you.

If I watch a fireworks display it does not

reduce the amount available to you. Similarly, public goods are

non-excludable, i.e. a user cannot be easily prevented from

consuming it. This creates the ‘free-rider’ problem. Extending the

fireworks example, while I will not pay to enter the stadium I can watch

from my apartment balcony at no charge. Allowing for externalities

(discussed below) there is in fact a spectrum of goods ranging from pure

private to pure public.

x -

Externalities

(MKM

C10/211-221:

198-216;

219-238;

201-219)

The Standard Model assumes that market

price ‘internalizes’ all relevant costs and benefits. This means the

consumer captures all benefits and the producer pays all costs at market

price. An externality means there are costs or benefits not captured by

market price, e.g., the social benefits of higher

education or the health costs of pollution.

7.

Is

Economics a Science?

(MKM C2/22-9:

19-26;

20-29)

Ideology & Theology assert Certainty. Science asserts Doubt.

HHC 23/06

“In the days when an idea could be silenced by showing that it was

contrary to religion, theology, was the greatest single source of

fallacies. Today, when any human thought can be discredited by branding

it as unscientific, the power exercised previously by theology has

passed over to science; hence, science has become in its turn the

greatest single source of error.” (p. 480)

Michael Polanyi, “Scientific

Outlook: Its Sickness and Cure”, Science, New Series, 125

(3246), March 15, 1957, 480-484.

It seems to me that this failure of the economists to guide policy more

successfully is closely connected with their propensity to imitate as

closely as possible the procedures of the brilliantly successful

physical sciences - an attempt which in our field may lead to outright

error. It is an approach which has come to be described as the

“scientistic” attitude - an attitude which, as I defined it some thirty

years ago, “is decidedly unscientific in the true sense of the word,

since it involves a mechanical and uncritical application of habits of

thought to fields different from those in which they have been formed.”

(p. 3)

F. A. von

Hayek, “The

Pretence of Knowledge”, Nobel Memorial Lecture, December 11, 1974,

American Economic Review, 79 (6), December 1989, 3-7

So, is Economics a science? Yes and no. It depends on how one defines

Science. The word Science comes from the Latin scire “to know”

which, in turn, derives from scindere “to split”. One gains

knowledge by splitting or reducing a question into smaller and smaller

parts until a fundamental unit or force is revealed. This is

reductionism. It should also be noted that the English word

'reason' derives from the Latin ratio meaning calculate. In

turn this means using numbers.

Until the Scientific Revolution of the

17th century such splitting and reducing was restricted to words. With

innovation of the experimental instrumental method, the Natural &

Engineering Sciences (NES) exploded. Ideally NES engages controlled

experimental conditions. It holds all factors constant, e.g.,

heat, humidity and air pressure, then changes one or introduces a new

variable (cause) to see the result (effect). Then repeat to confirm

results. Peer review then involves other scientists replicating the

experiment and obtaining the same results under the same controlled

conditions.

In the 20th century new disciplines of the

NES emerged that I call ‘Synthetic Sciences’. These include

climatology, ecology and environmental studies. Rather than reducing a

question to ever smaller components (reductionism), the synthetic

sciences weave them together into a functioning whole (synthesis). This

whole is usually represented in a highly complex mathematical model of

the biosphere, climate, ecology or natural environment. Controlled

experimental conditions are possible only for some components and

currently impossible for the functioning whole. Replicability remains

mathematical. The effects, however, of modeled changes can be assessed

against real world changes but on time scales varying from a day to 1,

5, 50, 5,000 or more years into the future.

i- Sciences of the Natural & Artificial

Both the traditional and emerging

synthetic NES remain subject to the laws of nature. Economics, however,

is a Social Science. It is, to use a term coined by economist Herbert

Simon, ‘a science of the artificial’. Economics and all other Social

Sciences are primarily governed by human laws, not the laws of nature.

And human laws, unlike the laws of nature, are very mutable indeed.

Consider recent changes in banking law and

introduction of new technology that transformed the definition of a

successful business model. Think of the so-called FANGs: Facebook,

Amazon, Netflix and Google. Think of negative interest rates.

ii - Induction & Deduction

Like the traditional and synthetic NES,

the Social Sciences use two forms of logic: induction and deduction.

Induction involves reasoning from a particular observation to a general

conclusion, e.g., from an observation comes a theory. Deduction involves reasoning from the general to a

particular. In this course, deductive logic is the engine of analysis.

You will be given a set of fixed assumptions defining an initial

equilibrium. One assumption will be changed. You must deduce the

result.

iii – “Let Us Assume” & Ceteris Paribus

(MKM C2/22-4: 19-21;

20-22;

18-20)

An expression often heard from economists

is ‘let us assume’. Consider the joke about the economist,

mathematician and physicist marooned on a desert island with crates of

canned food and no can opener. The physicist says: I can start a fire

and blow the top off”. The mathematician says: “And, I can calculate

the trajectory of the food so we can catch it.” The economist says:

“Let’s assume we have a can opener”. Laugh, laugh, laugh, stupid

economist!

But consider. The physicist has no

equipment to measure the energy content of the fuel for the fire, nor

instruments to measure the can’s tensile strength and therefore cannot

determine when it will blow. The mathematician cannot, therefore,

calculate the trajectory of the food. The economist, on the other hand,

looks for a sharp rock to act like a can opener. One of my professors,

Gilles Paquet, called economists tool-bearing animals with the head

serving as the tool box. The deductive logic of economics is one such

tool and is used in other disciplines including Law and the NES.

One of the most important and regularly

used assumptions of Economics is ceteris paribus or ‘all other

things being constant’. Thus in analyzing a given phenomenon economists

begin by assuming all factors or forces are constant and then changes

one. This is a critical in economic analysis. For example, if the

price of a good or service changes, analysis is nearly impossible if the

price of all substitutes changed at the same time. To determine the

effects of a price change, economists assume all other prices remain

constant (in the first round).

In effect, the controlled experimental

conditions of the NES become a set of fixed assumptions in Economics, a

model. Changing one controlled condition or introducing a new variable

(cause) leads to a result (effect). Changing a fixed assumption of a

model or introducing a new variable in Economics (cause) leads to a

changed equilibrium (effect).

iv - Positive & Normative (MKM C2/30:27;

28; 25-26)

As a science of the artificial Economics

answers two types of questions. The first type ask: What is? Such

questions are called positive, i.e., they involve no value

judgment. The second asks: What ought to be? Such questions are called

normative, i.e., they involve a value judgment. For example, it

is a positive statement to say about 20% of Canadians live in poverty.

It is a normative statement to say, for reasons of Equity, we should

redirect national income to help them.

v - Observation & Measurement

(MKM C2/22-4:

19-21;

20-22;

18-20)

It is usually forgotten that the

Scientific Revolution involved the design and construction of

instruments that can measure and report experimental results. Such

instruments reach spaces and places above, below and beyond the reach of

the human senses. Ever tried to manipulate DNA by hand? One of the

strengths of the NES is that once calibrated such instruments report

back without human mediation of the evidence.

What distinguishes the Social Sciences

(sciences of the artificial) from the NES is that every step of the

evidentiary trail is mediated by human beings from marketing surveys to

final data manipulation. Consider the Census.

The Census is something that North

American economists rely on for in-depth measurement of a range of

economic phenomenon including the Census of Population (age and other

demographic characteristics as well household expenditures and consumer

capital goods) and the Census of Business Enterprise. While there are

technical limitations to the Census, e.g., does it ask questions

that elicit meaningful answers, there are also social limitations. In

continental Europe, for example, the Census of Population is not very

reliable because of traditional suspicion of government many, many

people simply do not answer or even lie. Similarly, different companies

use different accounting methods and when answering the Census of

Business do not necessarily use the same Generally Accepted Accounting

Principles (GAAP).

The bottom line: numbers, particularly in

the sciences of the artificial, have quality. They are collected using

inherently imperfect methodologies. They have parents who may have

their own agenda, some abusive. In the NES, this last point is referred

to as ‘experimenter expectation’. Again, what distinguishes Social

Science evidence from that in the NES is that every bit is mediated by

human beings from marketing survey to data manipulation.

Economics is better off than other Social

Sciences because evidence is generated by transactions that usually leave a

record without interfering with individual behaviour. Thus when one

buys a chocolate bar, a car, a stock or bond or a house records are

generated for tax and other purposes allowing statistical evidence to be

collected. In addition such transactions are conducted using the same

unit of account: money. Compare this to a sociologist studying the

partying behaviour of first year university students. He or she must

rely on survey information provided by students and/or attend parties as

a participant observer risking a ‘contact high’ and other forms of

subjective engagement.

vi– Modeling & Testing (MKM C2/24-9:

21-26;

22-27;

20-24)

The world is a very complex place. Models

are used to reduce this complexity. For those interested in the historical

and philosophical roots of modeling, please see:

Observation #4:

Modeling.

An economic model is a simplified

description of the

whole

or some part of the economic system, e.g.,

Supply and Demand. A set of assumptions or premises are made and

conclusions deduced. One thing both inductive and deductive model

building share in common is ‘assumptions. Assumptions are used to

ignore or simply hold constant selected variables. A model thus tries

to explain how certain variables react to changes in other variables,

but not all possible variables. The world is simply too complex to be

fully modeled.

Having constructed a model of some

economic phenomenon, economist then attempt to test its predictions

against empirical evidence including statistics and descriptive

observation. If the predictions accord with the evidence, the model or

theory is held true (for the time being, i.e., until new evidence

contradicts the model); if not, it is rejected.

Many theories in Economics, however,

simply cannot be tested. For many we simply lack the technology. For

example, the theory of revealed preference developed by Paul Samuelson.

It says preferences of consumers are revealed by actually buying goods &

services, not by what they say. However, it is simply not possible to

track a large number of consumers over time holding all other factors

fixed, for example, age, income and education, all of which affect

taste.

Two recent developments - behavioural

economics and social media - expand our potential technologies of

measurement. Behavioural economics uses small scale experiments to test

selected microeconomic theories and assumptions, e.g., a narrow

definition of rationality. Findings have increasingly fed through to

public policy as policy ‘nudging’. In this regard, with an ever

expanding internet and social media marketeers can formulate

psychographic profiles of existing and potential consumers by data

mining Big Data. Such evidence, however, is not in the public domain.

It is proprietary.

Psychographic mining Big Data promises

confirmation or rebuttal of revealed preference but it is proprietary

and commercial in nature. As such there is no published methodologies

for outsiders to assess data quality nor access it for research

purposes. Other economic theories also could be put to empirical

testing if such new technologies of measurement were made accessible to

academic, business, non-profit and public sector economists. It is not

widely recognized that years of public sector austerity have had

debilitating effects on Statistics Canada and other national statistical

agencies on the quantity and quality of their products. Private sector

assistance could help compensate for the damage done and thereby foster

public policy that is better evidence based. Is the corporate sector

willing? How could privacy be protected?

vii - Conclusion

First,

Economics is a ‘science of the artificial’, one of the Social Sciences.

As such it is primarily subject to mutable human law not the invariable

laws of nature. A bridge stands or falls based on the constant and

unchanging laws of physics. Economic theories, however, stand, fall or

mutate with the changing cultural, historical, legal and technologic

conditions of society.

Furthermore, the Social Sciences are not,

in general, experimental sciences. Their social theories cannot be

directly tested. There are no replicable laboratory conditions for an

economy let alone an entire society. There are, in fact, strict laws

limiting human experimentation. Evidence is thus primarily generated by

observation. With respect to Economics I write ‘’in general’ to allow

for behavioural economics which conducts small scale or

micro-experiments whose findings while insightful do not currently

permit construction of an overarching theory of Economics.

Second,

without access to objective instrumental measurement as in the NES, the

evidentiary trail in the Social Sciences is generated and mediated by

human beings from beginning to end. Unlike the other Social Sciences,

however, Economics has access to the next best thing to a scientific

instrument: Money. Daily life leaves an evidentiary trail of monetary

transactions. Whether it is the bread we eat or the video streaming

service to which we subscribe all can be counted using money as the unit

of account. You can’t compare apples and oranges but you can compare

their price per dozen.

Third,

the inherent limitations of the Social Sciences highlights the fact that

Science means more than experimental science with replicability as its

standard. In fact, the rules of evidence and how it is collected,

organized and systematized varies dramatically between knowledge

domains: the Natural & Engineering Sciences (NES), the Humanities &

Social Sciences (HSS) and the Arts. Science, in this general sense,

means an organized and systematized body of knowledge, a way of

knowing. Accordingly, in Economics as in the other Social Sciences many

theories are accepted not because they can be tested but because they

are ‘believable'.

Fourth and finally, the word 'economy' derives from the ancient Greek oikos meaning ‘house’

and nemo meaning ‘manage’, i.e. managing the house. It shares

this root with ‘ecology’ deriving from oikogie meaning modes of life and

relations within

and about

the house. Ekistics - the science of human settlement - also

derives from oikos but in the sense of founding an ancient Greek colony

like Syracuse or the numerous city states established by Alexander the Great in

India at the end of the 4th century before the common era.

Economics as management of the household raises the question: What is the

relevant household? In its original sense it was the self-sufficient or

autarkic rural estate. Management, however, ascended to higher orders as the

self-sufficient village, town, city and most recently the Nation-State. A

global society in which there is contiguous urban development separated only by

natural barriers – mountains, oceans and deserts - has been called the

Ecumenopolis – the World City - by urban planner Constantinius Doxiadis; its

global reality is visible in a composite photograph of “The

World at Night” published by NASA in the year 2000. If seeing is believing

then it provides visual evidence of humanity enframing its home planet. We see

a World City whose shimmering lights soar out into the infinite blackness of

space. It shows us one planet, one biosphere and one human race lighting

up the darkness. However, there is not yet a global economics, no generally accepted

model for managing the planet.

Analytic geometry has since been extended to

n-dimensional space. In this course you will make extensive

use of what Alfred Marshal, father of the Standard Model,

Analytic geometry has since been extended to

n-dimensional space. In this course you will make extensive

use of what Alfred Marshal, father of the Standard Model,  shows the relationship between price and

quantity demanded of a good or service. It shows a consumer’s

willingness to pay different prices for different quantities of a good

or service. All things being equal, the Demand Curve is downward

sloping reflecting the Law of Demand.

shows the relationship between price and

quantity demanded of a good or service. It shows a consumer’s

willingness to pay different prices for different quantities of a good

or service. All things being equal, the Demand Curve is downward

sloping reflecting the Law of Demand.  shows the relationship between price and

quantity supplied. It shows the willingness of a producer to sell. All

things being equal, the Supply Curve is upward sloping reflecting the

Law of Supply. Assuming the cost of inputs and technology remain

constant, there will be movement up and down along the curve as price

changes. If any of the constants change, however, the Supply Curve will

shift [

shows the relationship between price and

quantity supplied. It shows the willingness of a producer to sell. All

things being equal, the Supply Curve is upward sloping reflecting the

Law of Supply. Assuming the cost of inputs and technology remain

constant, there will be movement up and down along the curve as price

changes. If any of the constants change, however, the Supply Curve will

shift [ Markets can be:

Markets can be: