Microeconomics

Macroeconomics

SISTERetrics

SITES

Compleat World Copyright Website

World Cultural Intelligence Network

Dr. Harry Hillman Chartrand, PhD

Cultural Economist & Publisher

©

h.h.chartrand@compilerpress.ca

215 Lake Crescent

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan

Canada,

S7H 3A1

Launched 1998

|

Macroeconomics 6.0 Global Economy (cont'd)

|

|

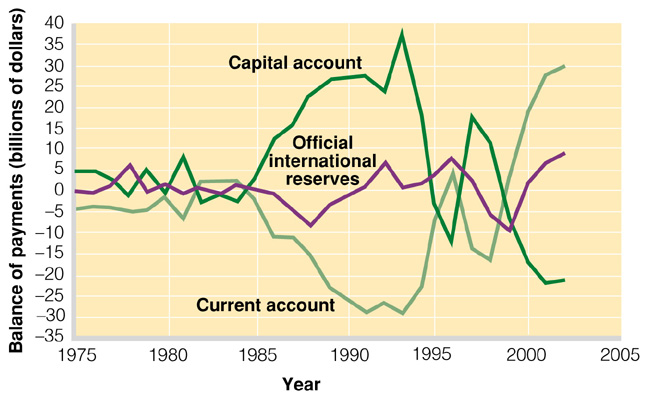

1. Balance of Payments (MKM C12/281; 264; 273) The balance of payments is the score sheet for all economic transactions during a given period between one country and its residents (including Government) and all other countries. Transactions are reported using double entry bookkeeping with credit entries balanced on the debit side, and vice versa. The balance of payments thus necessarily balances. There can be no surplus or deficit in a country's balance of payments as a whole. A country's balance of payments is divided into two major sections: the current account and the capital account. The current account, in turn, is subdivided into goods and services and transfer payments. The capital account is subdivided into non-monetary (sale/purchase of real assets) and monetary (payment for work) sectors. The balance of payments is part of the System of National Accounts (MBB Fig. 17.1- Canada).

The overall balance of payments comprises the current account (merchandise and services), unilateral transfers (gifts, grants, remittances, and so on), and the capital account (long-term and short-term capital movements). If payments due in exceed those due out, a country is said to be in surplus; and when payments due out exceed payments due in, it is in deficit. The surplus or deficit must be balanced by a monetary movement in the opposite direction. Consequently the overall balance must be equal, i.e., an accounting identity. It is important to distinguish the 'trade balance' and the balance of payments. The trade balance refers to trade in goods & services (sometimes considered separately, goods vs. services). An export surplus or deficit in goods (merchandising trade account) may be matched by net sales of services (service account). There would then be no deficit in goods and services as a whole. Thus the balance of payments is a broader and more significant measure than is the balance of trade in goods and/or services. In turn, the trade balance is different than the current account balance. A nation with a current account deficit is ipso facto decreasing its capital assets abroad (including gold) or increasing capital liabilities to foreigners. A nation with a current-account surplus is gaining foreign assets or reducing foreign liabilities. A deficit in the trade balance does not necessarily affect a country's exchange rate. There may be a matching inflow of investment capital that strengthens the immediate exchange position and builds up a country's future exporting capacity. Similarly, a surplus in the trade balance does not assure a strong exchange rate. For other explanations see: The Economist Glossary - Balance of Payments; Government of Canada Balance of Payments; Statistics Canada Wikipedia Balance of Payments; Balance of Payments Accounts: Definitions

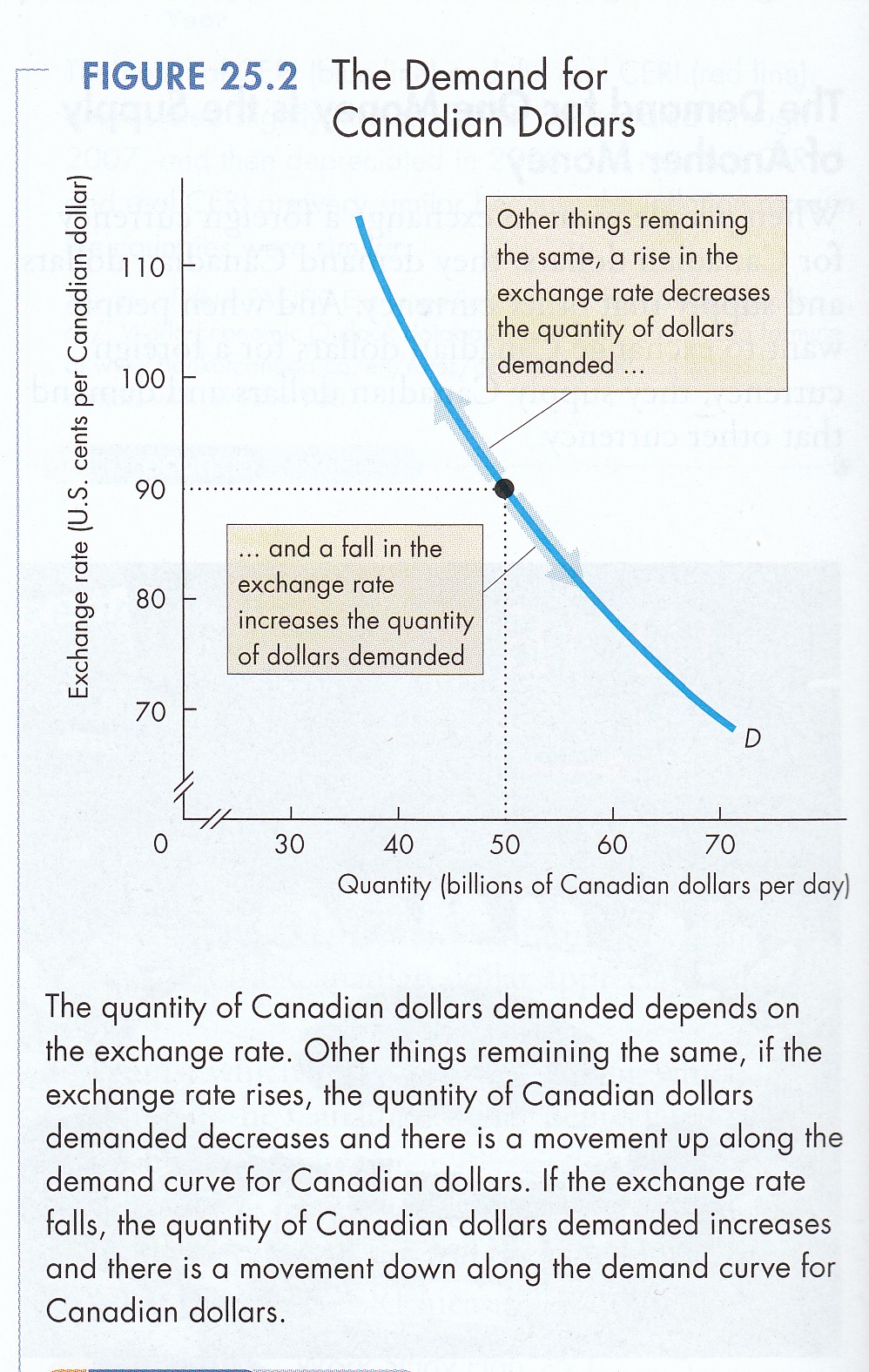

2. Exchange Rate (MKM C13/ 286-291: 268-272; 278-282) The 'exchange rate' is the price of a country's money in relation to another country's money. Generally when Canada's exports increase, the exchange rate increases, i.e., fewer Canadian dollars buy a unit of foreign currency. Increased foreign demand for Canadian currency makes Canadian goods more expensive. As Canadian goods become more expensive, exports decline. Decreased demand for the Canadian dollar then tends to lower the exchange rate making Canadian goods cheaper and so on and so on in a floating exchange rate system. The current floating exchange rate system is 'managed' by agreement among the larger central banks. Accordingly, a currency may rise or fall within some limit with respect to another, say 10%. No intervention is required. If a currency rises or falls more then central bank action may be taken to strengthen or weaken a given currency in exchange markets. It important to note that the foreign exchange market is, in the main, binary, i.e., there is market for the $Cdn and the $US and a separate market for the $Cdn and the British £ and yet another for the $Cdn and the European €. Accordingly, while a national currency is the generally accepted medium of exchange, unit of account, store of value and income earning asset within a given country, it is just another commodity on the currency exchange market being bought and sold like pork bellies, soybeans and other goods & services. (a) Dollar Demand (P&B 7th Ed Fig. 25.2)

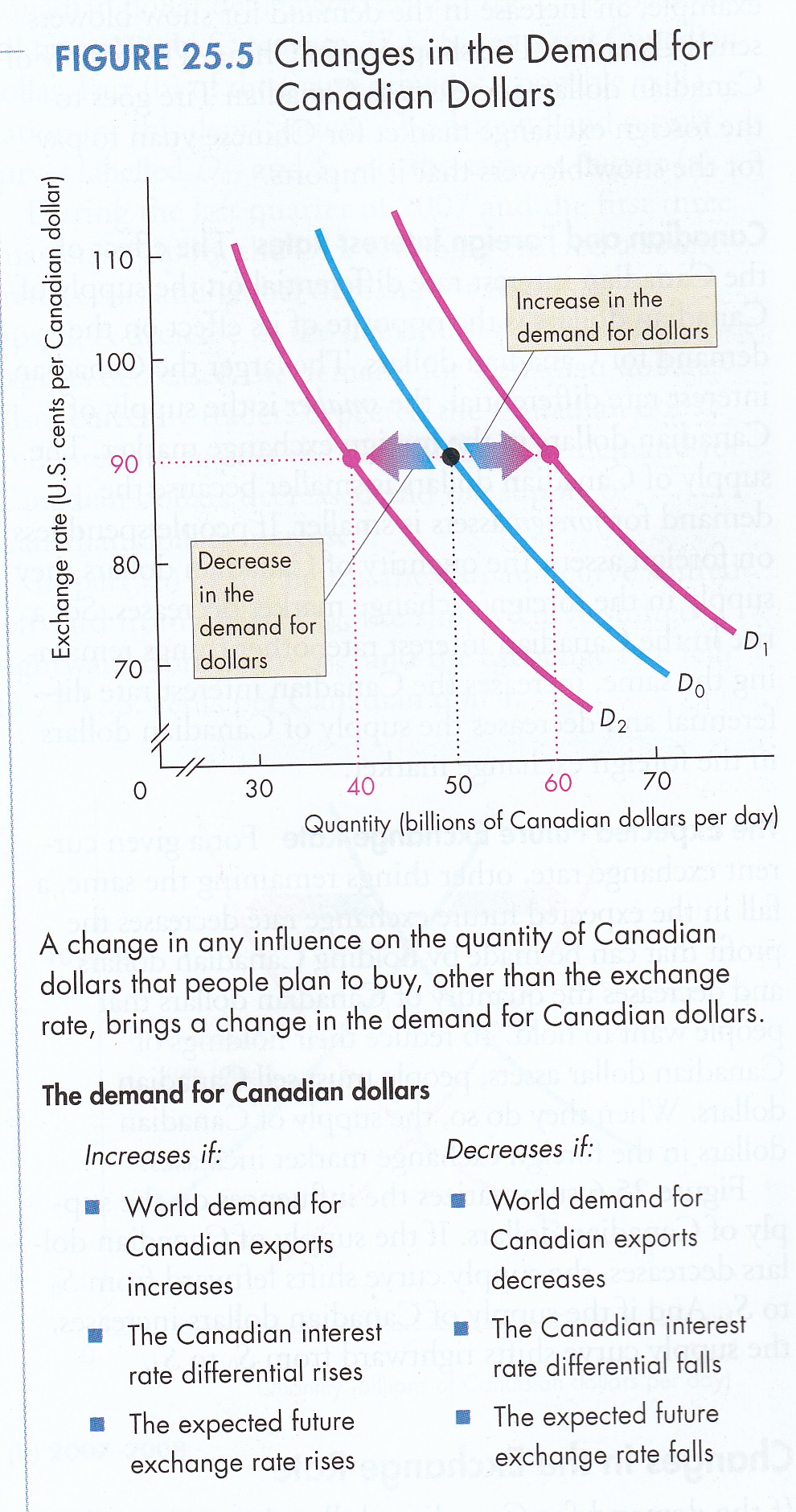

(i) Global Demand If global demand for Canadian goods & services increases then more dollars must be bought on the foreign exchange market by foreign buyers. Quite simply, foreign currency is not a generally accepted medium of exchange within a country. Accordingly, a foreign buyer must first exchange foreign currency for Canadian dollars and then purchase Canadian exports. This is the foresign exchange market. If demand for Canadian goods & services goes up the demand curve shifts to the right; if export demand goes down the demand curve shifts to the left. The exchange rate accordingly rises and falls in response to changes in demand. (ii) Interest Rate Differential Investors are concerned with the ‘real’ rate of return and the ‘real’ interest rate. At a given point in time the nominal interest rate in a country is say 6%. Inflation, however, is running at an annual rate of 3%. The ‘real’ interest rate is 6 – 3 = 3%. Similarly, at a given point in time, the ‘real’ interest rate in country A is 6% while 3% in country B. The interest differential will encourage investors in B to shift monies to A where they can earn a higher real interest rate. This would represent a capital account inflow to A and outflow from B. If the differential increases, there will be new demand for currency A shifting A’s currency demand curve to the right. Investors must first acquire currency A on the exchange market before they can complete the transaction, i.e., increased demand for currency A. If the differential shrinks, so does demand for currency A and its demand curve shifts to the left. Assuming a fixed supply curve the exchange rate will rise in the first case and fall in the second. (iii) Expected Future Exchange Rate The demand for dollars is like that for any commodity. If one expects its price to rise tomorrow one runs out and buys it today, i.e., an increase in demand shifting the curve to the right. Similarly, if one expects the price (the exchange rate) to fall tomorrow one holds off purchasing today, i.e., a decrease in demand and the curve shift to the left. Assuming a fixed supply curve, the exchange rate rises in the first case and falls in the second.

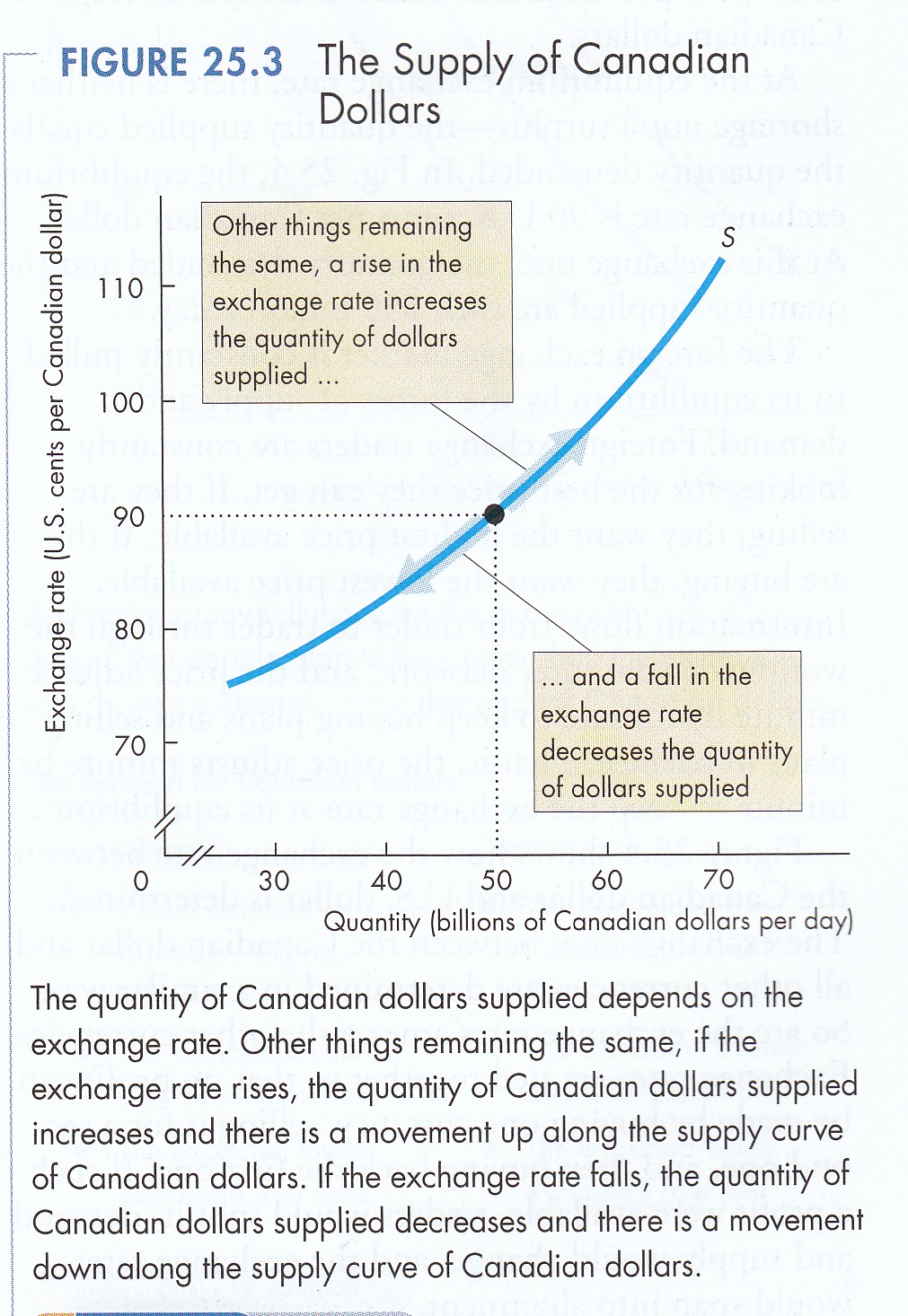

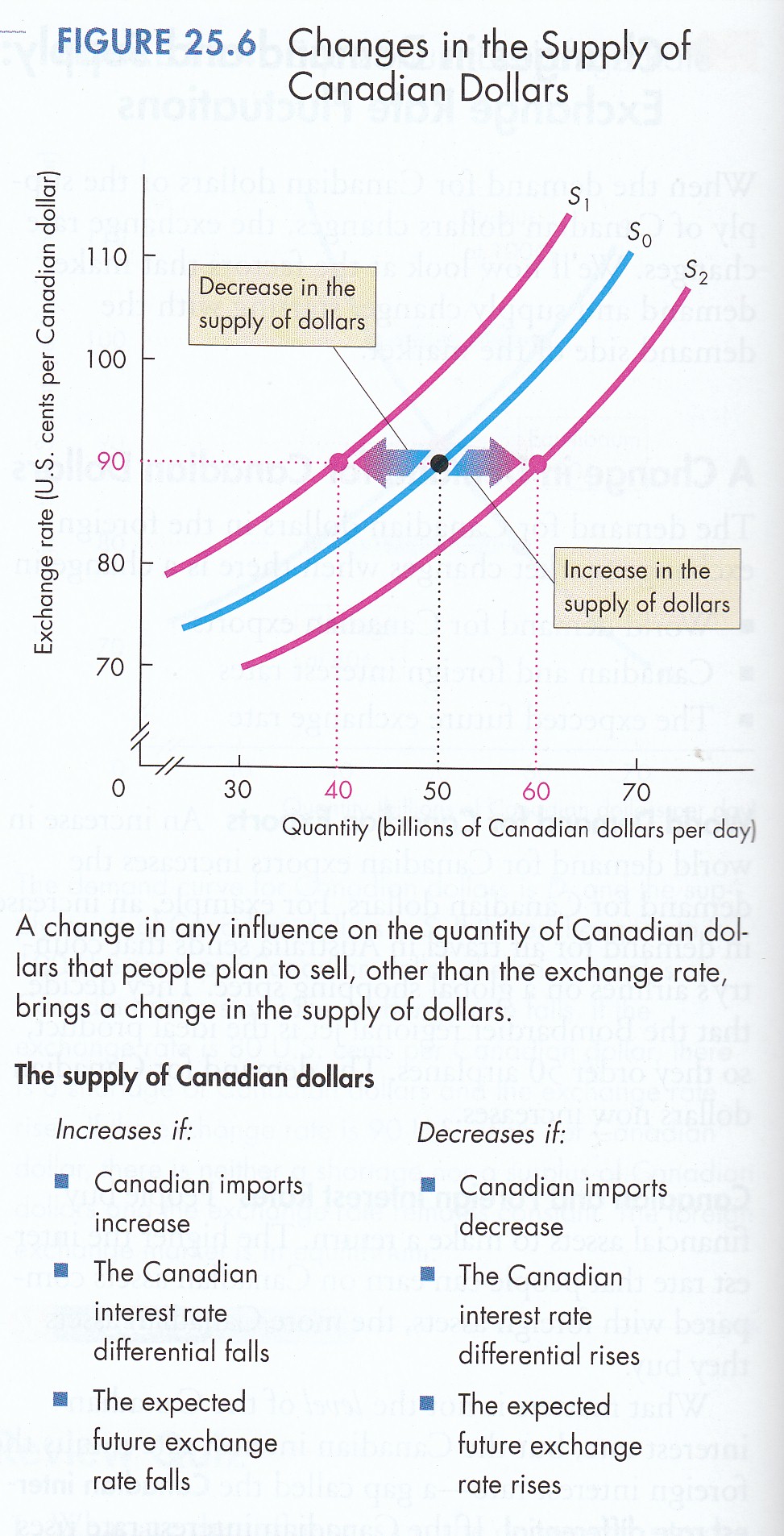

(b) Dollar Supply (P&B 7th Ed Fig. 25.3; R&L 13th Ed Fig. 35-3) Like any commodity the Canadian dollar is subject to the Law of Supply: higher the price greater the supply; lower the price lower the supply. The supply of dollars to the foreign exchange market has several sources. The central bank keeps reserves of foreign currencies so do the chartered banks and some other deposit taking institutions. Some large multinational corporations also have foreign currency reserves on hand. Furthermore, there are currency traders and speculators like George Soros – the man who broke the Bank of England and remains subject to arrest in Malaysia. Currency speculation involve predicting changes in exchange rates – buy cheap, sell high. In the case of smaller economies currency speculators can cause exchange rates to rise or fall depending on their profit position thereby upsetting such economies, e.g., the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 that saw the Thai and then other southeast Asian economies to go into deep recession. Three factors affect supply: (i) Canadian imports; (ii) the differential between Canadian and foreign interest rates; and, (iii) the expected future exchange rate. (P&B 7th Ed Fig. 25.6)

If imports to Canada increase then Canadian dollars must be spent on the currency exchange market to buy foreign currencies with which to complete the transaction. This increases the supply of Canadian dollars and the supply curve shifts to the right. If imports decline fewer Canadian dollars are spent on foreign currency and the supply curve shifts to the left. Assuming a fixed demand curve the exchange rate will fall in the first instance and rise in the second.

(ii) Interest Rate Differential At a given point in time, the ‘real’ interest rate in country A is 6% while 3% in country B. The interest differential will encourage investors in B to shift monies to A where they can earn a higher real interest rate. This would be a capital account inflow to A and outflow from B. If the differential increases, there will be new supply of currency B in the currency exchange market shifting B’s currency supply curve to the right. Investors must first acquire currency B on the exchange market before they can complete the transaction, i.e., increased supply of currency B. If the differential shrinks, so does supply of currency B shifts to the left. Assuming a fixed supply curve the exchange rate will falls in the first case and rises in the second. (iii) Expected Future Exchange Rate

The supply of dollars is like that for

any commodity. If one expects its price to rise tomorrow one

waits, i.e., an decrease in supply shifting the curve

to the left. Similarly, if one expects the price (the exchange rate)

to fall tomorrow one sells today, i.e., an increase

in supply and the curve shift to the righ. Assuming a fixed demand

curve, the exchange rate rises in the first case and falls in the

second.

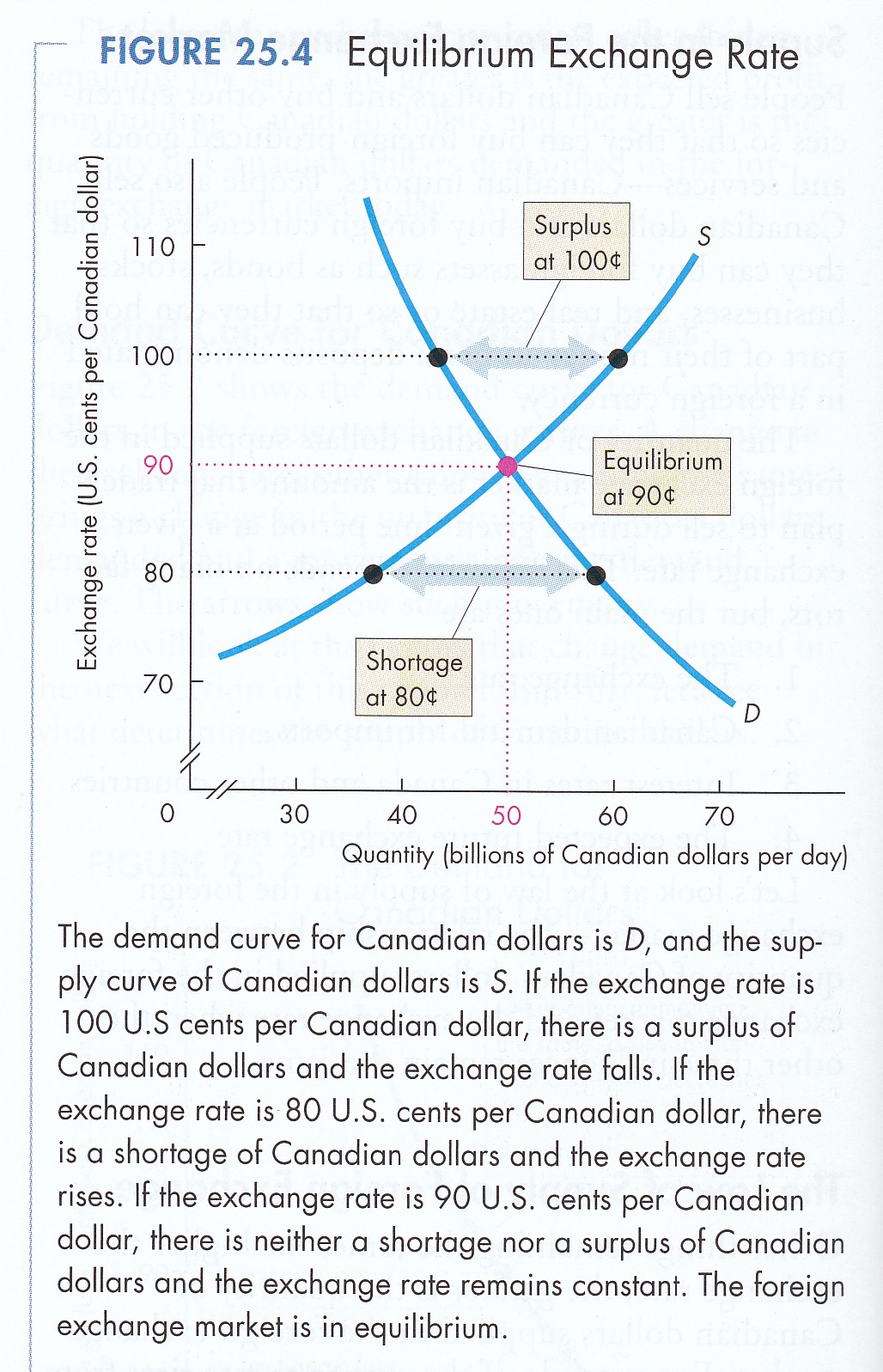

(c) Equilibrium Exchange Rate (P&B 7th Ed Fig. 25.4; R&L 13th Ed Fig. 35-1) All things being fixed there will be, at a point in time, a demand and supply of dollars on the foreign exchange market. Again, this market is binary, Canadian dollars for US dollars; Canadian dollars for British pounds, etc. Where the willingness to buy meets the willingness to sell a stable market equilibrium is created. If the exchange rate rises above equilibrium supply exceeds demand and a surplus is created resolved by a lowering of the price. If the rate drops below equilibrium demand exceeds supply and a shortage is created resolved by bidding the price back up to equilibrium. That equilibrium, however, depends on the constancy of exports, imports, interest rate differentials and expectation of the future exchange rate. Change these and you shift the curves.

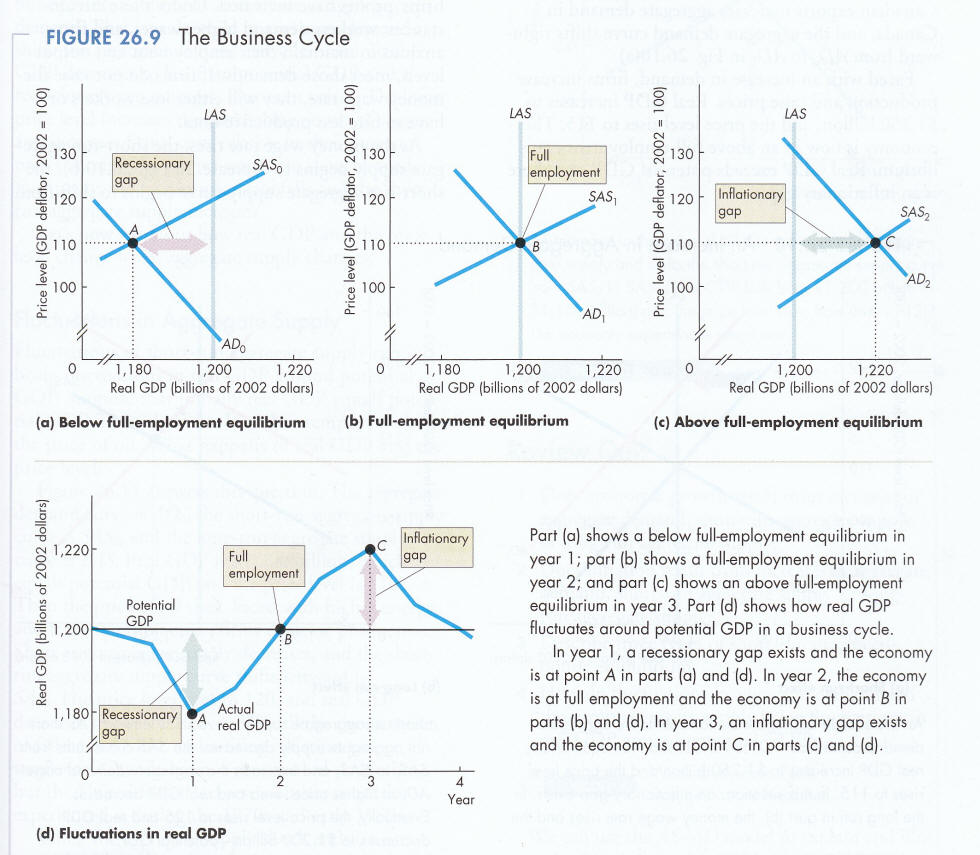

(d) Market Intervention (P&B 7th Ed Fig. 25.7) As previously noted, the current floating exchange rate system is 'managed' by agreement among the larger central banks. Accordingly, a currency may rise or fall within some limit with respect to another, say 10%. No intervention is required. If a currency exchange rate rises (appreciation of a currency) or falls (depreciation of a currency) beyond 10% then central bank action will be required to strengthen or weaken its currency in exchange markets. How? By buying or selling its currency on the foreign exchange market. Sometimes the actions of a given central bank is simply insufficient. In the short run larger central banks may then coordinate the buying and selling of a given currency to re-establish market equilibrium. If the problem persists then either a new range may agreed upon, say 15%, or the World Bank and/or International Monetary Fund may provide financial support in exchange for structural and other changes to the domestic economy in distress. Sometimes governments resort to exchange controls (sometimes combined with import licensing) to allocate foreign exchange more or less directly in payment for specific imports. At times, a considerable apparatus is assembled for this purpose, and, despite "leakages" of various kinds, the system has proved reasonably efficient in achieving balance on external payments account. Its chief disadvantage is that it interferes with normal market processes, thereby encouraging rigidities in the economy, reinforcing vested interests and restricting the growth of world trade. On the other hand, some countries, e.g., Argentina, will impose an export tax to keep domestic prices low. Whatever method is chosen, the process of adjustment is generally supervised by some central authority -- the central bank or some institution closely associated with it -- that can assemble the information necessary to ensure that the proper responses are made to changing conditions. Also see: The Economist Glossary - Exchange Rate; Wikipedia - Exchange Rate; 3. Trade & The Domestic Economy As we have seen a closed or autarkic economy without foreign trade can only consume what it produces. It is stuck on its production possibility frontier. Similarly, investment (I) in a closed economy is exclusively dependent upon domestic savings (S), i.e., I = S. Similarly, the domestic money supply must equal domestic demand for money, i.e., Ms = Md In an open economy, however, some domestic savings will be invested in foreign economies and some foreign savings will be invested in the domestic economy. Canadian investment abroad represents a leakage from the circular flow of income. In effect, Ms is reduced with implications for domestic interest rates (r) and hence investment. Foreign investment in Canada, on the other hand, represents an injection that, in effect, increases Ms with reversed implications. The overall effect depends upon the net of injections minus leakages, i.e., does Ms go up or down and hence does r go down or up and therefore does I go up or down? The monetary transmission mechanism at work. The net effect of capital flows in and out of a domestic economy is of concern to both the Central Bank and the elected Government. How do short- and long-run capital flows affect AD/AS short- and long-run equilibrium, the exchange rate, the interest rate, the inflation rate, the balance of payments (BOP)? What tools are available to Government and its Central Bank, alone or in a co-ordinated fashion, to manage short-run fluctuations and foster long-run national economic growth? At any point in time the first question is: What is the current state of the economy? P&B 7th edition

(a) Fiscal Policy Fiscal policy involves the taxing and spending power of the elected Government. What is important is that these powers are distributional in nature and can target specific sectors of the economy. Consider the balance of trade in goods & services. To promote exports and reduce a trade deficit Government can create a publicly owned export development bank to provide financing and other services to exporters. It can support industrial trade missions. It can subsidize domestic producers. The spending power at work. Alternatively, Government can exempt exports from sales & excise taxes. It can provide income tax and other special tax regimes to foster exports. It can impose tariffs and quotas on imported goods. The taxing power at work.

(b) Monetary Policy Monetary policy involves Central Bank management of the money supply and therefore interest rates as well as maintaining the stability of the currency at home and abroad. Tools include changing bank reserve requirement, the banker’s rate, open market operations, account shifting and moral suasion. Consider capital flight when large amounts of foreign investment leave a country over a short time period. The sale of the domestic currency increases its supply on foreign exchange markets shifting the supply curve to the right. This causes the exchange rate to drop below the desired level. The Central Bank can respond by entering the foreign exchange market buying domestic currency increasing demand shifting the demand curve to the right raising the exchange rate back to the targeted level. At the same time the Central Bank can reduce the domestic money supply thereby raising the interest rate differential with other investment destinations and attract back foreign investment.

These are examples of Government and the Central Bank acting independently. They could, however, coordinate their actions. Problems arise when the objectives of the two conflict. For example, the decline in the exchange rate in the monetary policy example above makes domestic goods & services cheaper on international market boosting domestic producers. This gains Government favourable political capital from domestic industry. The Central Bank, however, consider the declining exchange rate as bad for the economy and takes appropriate action. This can, as happened in Canada during the Coyne Crisis of the 1960s, lead to conflict between the Government and the Central Bank. The outcome of such a conflict depends on the degree of independence enjoyed by the Central Bank.

|

Like

any commodity the Canadian dollar is subject to the Law of Demand:

higher the price lower the demand; lower the price greater the demand.

From where does this demand emerge? Three factors affect demand: (i)

global demand for Canadian goods & services, a.k.a., exports; (ii) the differential

between Canadian and foreign interest rates; and, (iii) the expected

future exchange rate. The existing curve embodies current demand

factors. Change in a plotted variable causes movement along the

curve. A change in any of the three demand factors causes the

curve to shift

Like

any commodity the Canadian dollar is subject to the Law of Demand:

higher the price lower the demand; lower the price greater the demand.

From where does this demand emerge? Three factors affect demand: (i)

global demand for Canadian goods & services, a.k.a., exports; (ii) the differential

between Canadian and foreign interest rates; and, (iii) the expected

future exchange rate. The existing curve embodies current demand

factors. Change in a plotted variable causes movement along the

curve. A change in any of the three demand factors causes the

curve to shift