Microeconomics

Macroeconomics

SISTERetrics

SITES

Compleat World Copyright Website

World Cultural Intelligence Network

Dr. Harry Hillman Chartrand, PhD

Cultural Economist & Publisher

©

h.h.chartrand@compilerpress.ca

215 Lake Crescent

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan

Canada,

S7H 3A1

Launched 1998

|

Macroeconomics 3. Aggregate Expenditure & Demand (cont'd)

|

|

3.

4

The Multiplier

Introduced by Keynes in his 1936 The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money,

the Multiplier shows by how many times an

All

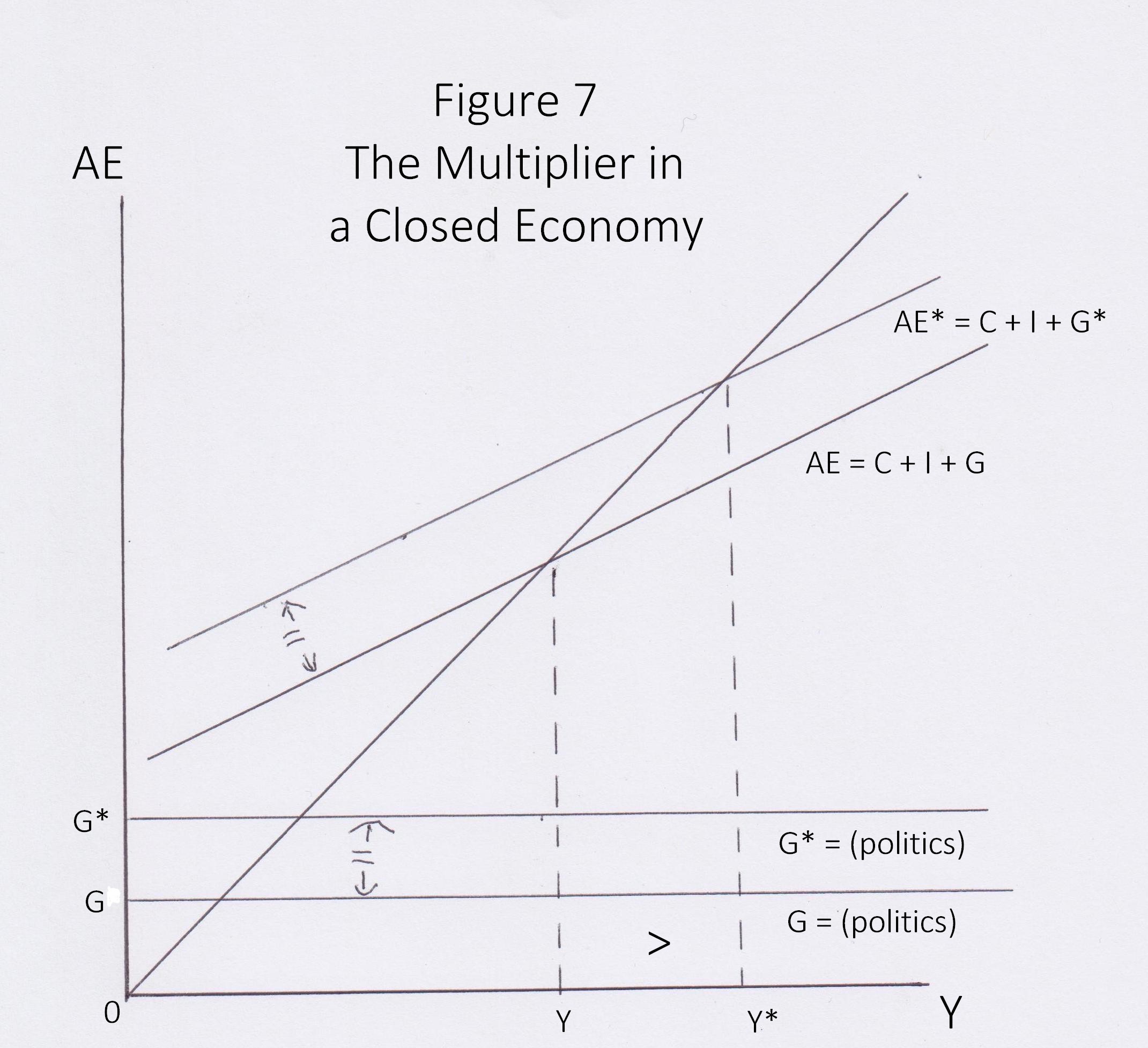

things being equal, the steeper the slope of the AE curve, the larger the

multiplier; the gentler the slope, the lower the multiplier (P&B

7th Ed Fig. 27.7).

Assuming b = .75 (75 cents of each additional dollar in income is spent on

consumption) then (1/1-.75) = (1/.25) = 4. It is important to note that the

Multiplier is a process spreading out over

time (P&B

Fig. 25.8). All

things being equal, the steeper the slope of the AE curve, the larger the

multiplier; the gentler the slope, the lower the multiplier (P&B

7th Ed Fig. 27.7).

Assuming b = .75 (75 cents of each additional dollar in income is spent on

consumption) then (1/1-.75) = (1/.25) = 4. It is important to note that the

Multiplier is a process spreading out over

time (P&B

Fig. 25.8).

iii -

Consumption, Income Taxes & Imports

The size of the multiplier depends on the slope of AE which, in turn, is determined by

the marginal propensity to consume (MPC), the marginal tax rate (MTR) and, in an

open economy, the

marginal rate of imports (MPM) In addition to the general Autonomous Expenditure Multiplier described above these include the: a) Government Expenditure Multiplier; b) Autonomous Tax Multiplier; c) Balanced Budget Multiplier; and, d) Impact of the Marginal Propensity to Import (MPM)

a)

Government Expenditure Multiplier (GEM) b) Autonomous Tax Multiplier (ATM) There are essentially two kinds of taxes - induced and autonomous. Induced taxes rise and fall as Y varies. In this way induced taxes like income tax act as automatic stabilizers of the economy. If Y goes up then the Marginal Tax Rate rises to a higher level (progressive taxation) and disposable income is reduced cooling the economy; if Y goes down the Marginal Tax Rate falls to a lower level and disposable income rises. Autonomous taxes do not vary with real GDP but rather are determined by Government. An increase in taxes decreases disposable income and hence consumption and therefore Y. The decrease in Y will, however, be greater than the increase in taxes (P&B 4th Ed Fig. 26.9). The Autonomous Tax Multiplier equals -b/1-b = ∆Y/∆T assuming a fixed Aggregate Price Level, a closed economy and the Marginal Tax Rate (MTR) is zero. Thus if b = .75 then ATM = .75/1-.75 = .75/.25 = 3. Thus an increase in taxes of $50 million will lead to a decline in Y of $150 million. The inverse of the ATM is the Multiplier associated with transfers. Transfers are like negative taxes, i.e., taxes are reduced. The Autonomous Transfer Multiplier is simply the negative of the ATM. Another related concept is 'tax expenditures' where Government selectively reduces taxes and losses revenue thereby.

iii - Balanced

Budget Multiplier (BBM) iv - Impact of Marginal Propensity to Imports (MPM) If, in a closed economy, we assume a MPC of .75, i.e., 75 cents of every dollar is spent on consumption then GEM is 1/1-.75 = 1/.25 = 4. If, however, the economy is open and MPM is .1, i.e., 10 cents on every dollar is spent on imported goods then, AEM is 1/1-.75-.1 = 1/.65 = 2.86. This again assumes a fixed Aggregate Price Level and the Marginal Tax Rate (MTR) is zero Economist study the business cycles - the ups and downs of the economy. As will be seen the Multiplier plays a significant role in Government's management of the cycle. According to the Dictionary of Economics and Business (Erwin Esser Nemmers, Littlefield, Adams, Totowa, New Jersey, 3rd Ed., 1976, pp. 54-5), the business cycle is: Rhythmic changes which take place in business conditions over a period of time. The phases of the cycle are called prosperity (peak, upswing, expansion), crisis (down-turn), depression (trough, downswing, contraction), and recovery (upturn, revival). Various explanations for the business cycle have been developed. In analyzing cyclical statistics a number of different cycles have been found, each named after the man who developed knowledge of it. Thus the Kitchin cycle is about 40 months, the Juglar cycle is from 8 to 14 years, the Spiethoff cycle about 20 to 30 years and the Kondratieff cycle (long wave) about 50 years. There are a many explanations for the business cycle including the: animal spirits theory endogenous theory exogenous theory innovation theory interaction of multiplier & accelerator theory inventory theory monetary theory overinvestment-oversaving theory psychological theory underconsumption theory weather (sunspots) theory

3.5 Aggregate Demand (MKM C14/340-7; 316-324; 328-333; 305-310)

Aggregate Expenditure is calculated assuming a

fixed Aggregate Price Level (P) At a given P the various economic

actors - households, firms, governments, exporters and importers - make their

expenditure decisions:

Y = C +

I + G + X – M. Change P and there is

a different result. For each level of P a different level of Y exists.

Plotting all different levels of P (graph below) with corresponding levels of Y

and we can plot the Aggregate Demand Curve (ADC).

The ADC is downward sloping.

i - Price Level; ii - Expectations; iii - Fiscal & Monetary Policy; and, iv - Global Economy. All things being equal: the higher P the lower Y measured as real GDP (P&B 7th Ed Fig. 26.4; R&L 13th Ed Fig. 23-1 & 23-2; MKM Fig 14.3). And, as in Micro, there are income and substitution effects associated with price changes. In Macroeconomics, the income effect is called 'the wealth effect'. If prices rise, wealth falls as financial assets (bank accounts, stocks and bonds) buy less. People feel poorer and buy less. There is movement up the ADC with declining Y and vice versa. In Macro the substitution effect (shifting from the more to less expensive) involves future prices (expectations) and foreign prices (imports). If prices are expected to go down tomorrow people will buy less today. At the extreme, this delay in spending can lead to deflation (the expectation of ever lower prices) with associated costs including the liquidity trap. Similarly, if Canadian prices go up but foreign prices remain constant then foreign prices (imports) become relatively less expensive and Canadians buy more foreign and fewer Canadian goods & services. Domestic factors of production are not employed and less income is earned. At the extreme, this shift can lead to deindustrialization and associated costs including the decreased potential GDP of a Nation-State. It is primarily expectations about future income, prices and profits that determine aggregate demand today. The expectation of an increase in future income leads consumers to increase aggregate demand today and vice versa. The expectation of increase future profits leads firms to increase their investment today shifting the ADC and vice versa. Similarly, the expectation of higher prices tomorrow (inflation) leads households and firms to increase purchases today and vice versa. Again, Keynes' expectations and John. R. Common's futurity: People live in the future but act in the present. iii - Fiscal & Monetary Policy

Fiscal policy involves taxation and government spending including

transfers to households and firms. If government spending goes up,

aggregate demand shifts up and

vice versa.

Taxation takes income from households to fund government spending. If taxes go down,

disposable income goes up and, all things being equal, aggregate demand shifts

up and

vice versa. Monetary policy involves changes in the

money supply and interest rate (the

cost of money). If interest rates go down investment goes up shifting the

ADC up and

vice versa.

Similarly, if the quantity of money increases households, firms and/or

government can spend more shifting the ADC up and

vice versa.

Growth or decline in population obviously affects AD. More or fewer households generate more or less demand shifting the ADC accordingly. Two principal global factors influencing domestic aggregate demand are the exchange rates ($Cdn) and foreign income (GDPf). If the exchange rate goes down, the dollar buys less foreign goods. Imports go down. Domestic goods & services become less expensive to foreign buyers and exports increase. Both cause the domestic ADC to shift up and vice versa. Similarly, if foreign GDP goes up they can buy more domestic goods & services increasing exports shifting the ADC up and vice versa. More will be said in 6.0 The Global Economy.

|

The implications of changes in P for the multiplier effect will be explored

later.

The implications of changes in P for the multiplier effect will be explored

later.