The Competitiveness of Nations in a Global Knowledge-Based Economy

The Economic Aspects of Copyright in Books

[1

(Ernest Cassel Professor of Commerce in the

Economica, New Series, 1

(2

May, 1934, 167-195

IF an economist needed encouragement or justification

for devoting time to the consideration of the effects of copyright legislation

on the output of literature, he might find it in the stimulating introduction

which Professor Frank H. Knight has contributed to the reissue of his Risk,

Uncertainty and Profit. “Having

started out by insisting on the necessity, for economics, of some kind of

relevance to social policy - unless economists are to make their living by

providing pure entertainment or teaching individuals to take advantage of each

other,” he discusses the conditions of relevance of economics to social policy,

and his “first and main suggestion” is that an “inquiry into motives might well,

like charity, begin at home, with a glance at the reasons why economists write

books and articles.” [2] Direct monetary profit from the sale of

what they write does not figure in Professor Knight’s suggestive discussion of

the motivation of economist-authors; although for three, if not four, centuries

the advocates of property in the right to copy have argued as though book

production were the conditioned response of authors, publishers and printers to

the impulse of copyright legislation. An inquiry into the rationale of

copyright seems therefore both worth while in itself and likely to prove of

general interest among students of economics.

There is, of course, a special difficulty in discussing

the subject of copyright, in that a writer has an unavoidable bias. How many of us approach the topic in the

spirit evinced by H. C. Carey in his Letters on International Copyright?

“The writer of these Letters

had no personal interest in the question

1. Presidential Address to the

2. London

School of Economics Series of Reprints, No. 16, pp.

xxv-xxvi.

167

therein discussed. Himself an author, he has since gladly

witnessed the translation and republication of his works in various countries of

Europe, his sole reason for writing them having been found in a desire for

strengthening the many against the few by whom the former have so long, to a

greater or less extent, been enslaved. To that end it is that he now writes,

fully believing that the right is on the side of the consumer of books,

and not with their producers, whether authors or publishers.” T. H. Farrer, at that time Permanent

Secretary to the Board of Trade, found it necessary to observe, when reviewing

the proceedings of the Royal Commission on Copyright in the Fortnightly

Review (December 1878), that authors, who were the principal witnesses, are

interested witnesses: “printed controversy is therefore, on the whole,

one-sided.” It is rather like

relying on articles in the daily newspapers for views on the waste involved in

Press advertising. Bias, and fear

of bias, make an author’s judgment on copyright a little unreliable. His readers must exercise particular

vigilance.

2 Book production without

copyright

A convenient approach to the whole subject is to try to

visualise the organisation of production of books, which we select as a typical

commodity for the purpose of this inquiry, in the absence of any sort of

copyright provisions. We may define

“the absence of copyright provisions” as the circumstances in which the buyer of

a literary product is free, if he so desires, to multiply copies of it for sale,

just as he may in the case of ordinary commodities. Would books be written in such

circumstances, and would they be published? Would firstly authors, and secondly

publishers, find it possible to make arrangements of a sufficiently remunerative

kind to induce them to continue in the business of book

production?

It should be observed at the outset that part of the

output of literature is written without thought of direct remuneration at all.

There are authors - scholars as

well as poets - who are prepared to pay good money to have their books

published.

1. H. C. Carey: Letters on International

Copyright (Preface to 2nd Edition.

168

It is conceivable that their output is in some cases

quite unaffected by demand conditions: so long as they can go on paying they

will go on writing and distributing their books. There is secondly an important group of

authors who desire simply free publication; they may welcome, but they certainly

do not live in expectation of, direct monetary reward. Some of the most valuable literature that

we possess has seen the light in this way. The writings of scientific and other

academic authors have always bulked large in this class. Economists are relatively fortunate in

serving a market which so frequently provides a margin above costs of

publication for the remuneration of the author; their colleagues in other

faculties are usually only too pleased to secure publicity for their

contributions to our literary heritage without financial subsidy from

themselves. Publications are, of

course, in varying degree essential for their careers, in professions other than

that of authorship. They seek

recognition of their claims as scholars; and published work they must have, even

at the cost of paying for it. Speak

to them on the subject of direct immediate return, and they reply in terms of

numbers of off-prints or “separates.” In just that way were authors quite

generally paid in this country in the sixteenth century: they sold their

manuscript outright to the publisher for perhaps at most one or two hundred

copies: on occasion a little money might also pass.

For such writers copyright has few charms. Like public speakers who hope for a good

Press, they welcome the spread of their ideas. Erasmus went to

4. The payment of authors without

copyright

What, however, of a third group of authors - the

professional scribes, who write for their living? Whether they sell their writings to

publishers, who buy them because they hope to sell copies, or whether they

publish them direct, their living depends on the direct proceeds from their

writing, and. in both cases their receipts depend on the number of copies sold.

Clearly, they - both author and

publisher - would gain directly from the restraint of all reprinting that

resulted in a. diminished sale of their own copies. If the purchase of a copy ceased to carry

with it the right to make further copies from it

169

for sale, the author and original publisher might

contrive to do much better for themselves, by the simple monopoly device of

restricting the number of copies offered on the market. They would do still better if they were

given the power to control also the supply of directly competing books, as early

publishers had in this country. It

goes without saying, of course, that that undoubted fact is not an adequate

reason why the general public should give them either degree of monopoly

power.

The belief has been widely held that professional

authorship depends for its continued existence upon this copyright monopoly; or

upon an alternative which is considered worse, viz, patronage. Even if that were true, it would still be

necessary to show beyond reasonable doubt that professional authors were worth

retaining at such a price as copyright. The output which monopoly alone can evoke

is not normally regarded as preferable to the alternative products which free

competition would allow to emerge. Patronage itself may not be wholly an

evil. There seems to be no reason

why a person who wants certain things written and published should not be at

liberty to offer payment to suitable people to do the necessary work. If the task is uncongenial, some authors

will need high remuneration, and others will no doubt decline any terms; but

many a builder has been willing in the past to erect even monstrous dwellings

for rich men who had their own ideas about architecture. Patronage has in the past provided us

with some magnificent literature, music, pictures, buildings, and furniture.

There have been patrons who have

given artists a very free hand in their work. Civil servants, secretaries of

commissions, lawyers and others have conceived it their normal duty to express

in imperishable language the views of their employers, with whom they may

personally have been in disagreement. To Macaulay, nevertheless, speaking in

the House of Commons at the second reading of Serjeant Talfourd’s. Copyright

Bill in 1841 (February 5th , Hansard, Vol. LVI), patronage was

the only alternative to copyright; and it was so objectionable that it justified

copyright. “I can conceive no

system more fatal to the integrity and independence of literary men, than one

under which they should be taught to look for their daily bread to the favour of

ministers and nobles.” ... “It is desirable that we should have a supply of good

books; we cannot have such a supply unless men of letters are liberally

remunerated, and the least

170

objectionable way of remunerating them is by means of

copyright.” ... “The system of copyright has great advantages, and great

disadvantages.” ... “ Copyright is monopoly, and produces all the effects which

the general voice of mankind attributes to monopoly.” ... “ Monopoly is an

evil.” ... “For the sake of the good we must submit to the evil; but the evil

ought not to last a day longer than is necessary for the purpose of securing the

good.” ... “The principle of copyright is this. It is a tax on readers for the purpose of

giving a bounty to writers. The tax

is an exceedingly bad one; it is a tax on one of the most innocent and most

salutary of human pleasures; and never let us forget that a tax on innocent

pleasures is a premium on vicious pleasures.” But Macaulay nevertheless preferred

copyright to patronage.

Is there no other alternative, in the absence of

copyright? For the moment it will

be sufficient to remark that professional writers have contrived in the

past to secure a price for their product, in such circumstances, provided always

that a market exists for it at all. And it must be borne in mind that

copyright in a particular work cannot itself create a demand for the kind

of satisfaction which that work and similar works may give, it can only make it

possible to monopolise such demand as already exists. Ultimately there must be patrons among

the public, whom the author must serve if he is to sell his product. In the early days, authors were sometimes

curiously employed. Italian

paper-makers in the fifteenth century integrated forward, and organised staffs

of writers to work on their paper, in the hope of thereby making the market for

their product more secure. 1 We are reminded of the present-day

integrations of paper manufacturers and newspapers employing journalists. In the days of manuscripts there was

never, so far as we know, any thought of author’s copyright. Manuscripts were sold outright, the

author knowing that the buyer might have copies made for sale; and the first

buyer knew that every copy he sold was a potential source of additional

competing copies. In selling

copies, he would therefore exploit with all his skill the advantage he possessed

in the initial time-lag in making competing copies. Moreover, copies of copies naturally

fetched lower prices, for errors in transcription are cumulative; and the owners

of original manuscripts could sell, first-hand copies at special prices. They therefore received a more permanent

margin from which authors could be paid. It was

1. See Putnam: Books and Their

Makers.

all very like the present-day trade in new fashion

creations - the leading twenty firms in the haute couture of Paris take

elaborate precautions twice each year to prevent piracy; but most respectable

“houses” throughout the world are quick in the market with their copies (not all

made from a purchased original), and “Berwick Street” follows hot on their heels

with copies a stage farther removed. And yet the

Was this all altered by the invention of printing? In fact, the making of copies was

regulated almost at once; but we know beyond any doubt that the reason was not

to ensure that authors were better remunerated. The early history of book production in

this country is most illuminating on this whole question, and it will be touched

upon in a moment. For the present,

it will suffice to observe that four centuries after the days of Caxton, many

English authors were regularly receiving payment from publishers in a country

which had no copyright law for foreign books. During the nineteenth century anyone was

free in the

172

authors, for “handsome sums” in fact to be paid. In the first place, there was the

advantage, well worth paying for, which a publisher secured by being first in

the field with a new book. To

secure priority American publishers regularly paid lump sums to English authors

for “advance sheets.” Secondly,

there was a “tacit understanding among the larger publishers in

1. E.g. Evidence of G. H.

Putnam.

2. Evidence, Professor John Tyndall, Question

5795.

3. E.g. Evidence of G. H. Putnam.

4. Evidence, Professor T. H. Huxley, Question

5610.

5. E.g. Evidence of T. H. Huxley, Question 5610. “I myself am paid upon books which

are published there: my American publisher remits me a certain percentage

upon the selling price of the books there, and that without any copyright which

can protect him.” Also John

Tyndall, Question 5775: “…I make an arrangement with my publishers ... in

Cf. also Herbert Spencer in a letter to The Times,

September 21st, 1895, reprinted in Various Fragments (1900):

“For a period of thirty years, during which English [works had no copyright in America, arrangements

initiated about iS6o gave to English authors who published with Messrs. —

profits comparable to, if not identical with, those of American

authors.”]

HHC: [bracketed] displayed on page 174 of

original

173

The significance of priority in the market, coupled with

a suitable size of edition and a corresponding price policy, as a deterrent to

competition is emphasised by an illustration. In an appendix to his book on The

Marketing of Literary Property, published in 1933, Mr. G. H. Thring

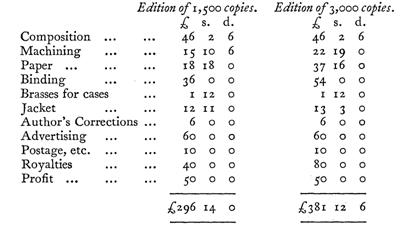

gives a number of accounts of the costs of book production. Taking his figures for a crown octavo

volume of 288 pages, eleven point, twenty-nine lines per page, an edition of

1,500 copies would involve approximately ₤300 to cover all publishing costs,

pay 10 per cent to the author and leave a profit of 16 2/3 per cent to the

publisher on all the costs, including royalty. That would mean an average wholesale

price of 4s. per copy, and a retail price of say, 6s. If the book were a success, and there

were no copyright law, a rival publisher might very probably come into the

market with a larger and therefore cheaper edition which would deprive the

author and first publisher of at least part of their anticipated receipts. They might, of course, lower the price as

soon as success showed itself to them, and reprint at once on a larger scale,

before competitors could formulate plans. A publisher who was more skilful in

judging public taste might, however, have embarked in the first instance on an

edition of, say, 3,000 copies, and if he calculated on receiving the same total

amount of profit himself from the venture and on paying twice the previous total

royalty to the author, the total sum involved might be about ₤382, or 2s. 9d.

per copy wholesale, corresponding to (say) 4s. retail. 1 A price as low as that would surely make

competitors hesitate before issuing,

1. The relevant detail of the costs, based on

figures of Mr. Thring, is:

174

late in the day, the still much larger rival edition

which would be necessary to make possible an appreciable further cut in

price. If a competing edition were

issued much more cheaply on poorer-quality paper and possibly unbound, it would

more probably tap a new market than divert the old. The abolition of copyright need not

therefore result in the complete abandonment of the business of book production

either by publishers or by professional authors.

5. The

early days of copyright

Our speculations will be made more fruitful if we pause

to inquire for a few moments into the nature and effects of copyright

regulations in this country.

The earliest records are hardly less enlightening than

those of our own generation. Regulation began in Tudor times with the

usual system of royal patents, conferring upon certain persons the monopoly of

the right to print particular books or classes of books. The patent system was of course applied

by a series of impecunious monarchs to all sorts of enterprise, but printing was

a special case, in due time expressly exempted (together with the manufacture of

armaments) from the Statute of Monopolies (21 James I, c. 3) of 1623. The printers did not fail to turn to

their own advantage the determination of the Crown to control the output of the

printing press. Many of the early

patent grants were, in their prime, profitable monopolies; one, for example,

comprehending all grammars in the Latin tongue, another the Bible, a third

covering all dictionaries, a fourth all books on law, and so on. A specialist writer, confronted by a

buyer’s monopoly for his class of work, had little hope of early publication,

still less of a profitable sale of his manuscript, if the monopolist had on his

hands a large stock of a competing book already printed. After 1557, when the general control of

the industry was entrusted to the Stationers’ Company, 1 a

comprehensive attempt was made at rationalisation in the interest of its

members. Each printer’s rights to

print were registered by the Company, and rights were assignable by one member

to another. Whenever exceptional

profits attracted interlopers, the case against unregulated competition was

argued by the

1. On the Stationers’ Company see A Transcript of the

registers of the Company of Stationers of

175

Company with a skill which our present-day trade

associations hardly excel. Already

in 1583 the report of Christopher Barker went to show that the patent

monopolies were not what they had been.

For instance, the “most profitable copy” in the country, a Latin grammar

for children, carried fixed charges which left the printers little more than

prime costs; “the printer with some greater charge at the first for furniture of

letters, hath the most part of it always ready set: otherwise it would not yield

the annuity which is paid therefor.” Monopolies cut into each other: Barker

himself had the patent for the Book of Common Prayer, but Master Seres had one

for a psalter comprising the most-used parts – “where I sell one book of common

prayer, which few or none do buy except the minister, he furnisheth ye whole

parishes throughout the realm, which are commonly a hundred for one.” Master Seres skimmed the cream. The industry already suffered from

serious surplus capacity: “there are 22 printing houses in

The era of the Star Chamber’s decrees and censorship was

a happy time for the members of the Stationers’ Company. Compared therewith,

confusion reigned as soon as the backing of the Star Chamber was removed by the

Long Parliament in 1641, and the Company’s petition of 1643 to Parliament

for greater powers of regulation 1 was

cunningly designed to make the flesh of an uncertain authority creep. “Too great multitudes of presses” set up

by “Drapers, Carmen and others,” were alleged to be in work, indiscriminately

printing “odious opprobrious pamphlets of incendiaries,” The ear of government

thus attuned, the petition proceeds to business. Even members of the Company were ignoring

property in copies, and if one complain he “shall be sure to have his copy

reprinted out of spite.” The

copyright monopoly is “a necessary right to stationers; without which they

cannot at all subsist.” ... “Property in copies is a thing many

ways

1. See Edward Arber, op cit., Vol.

1.

176

beneficial to the State, and different in nature from

the engrossing, or monopolising some other commodities into the hands [of] a

few, to the producing of scarcity and dearth, amongst the generality.” The stationers then pass to a statement

of the case for copyright which would not discredit an “economic adviser” to a

modern publishers’ association. The

first consideration is that books are luxuries, the demand for which is elastic,

and therefore monopoly cannot harm the public.

Books (except the sacred Bible) are not of such general

use and necessity, as some staple commodities are, which feed and clothe us, nor

are they so perishable, or require change in keeping, some of them being once

bought, remain to children’s children, and many of them are rarities only and

useful only to a very few, and of no necessity to any, few men bestow more in

Books than what they can spare out of their superfluities... And therefore

property in Books maintained among stationers cannot have the same effect, in

order to the public, as it has in other Commodities of more public use and

necessity.

The second consideration is that copyright monopoly

would result in more and cheaper books.

A well-regulated property of copies amongst stationers,

makes printing flourish, and books more plentiful and cheap; whereas Community

(though it seems not so, at first, to such as look less seriously, and

intentively upon it) brings in confusion, and many other disorders both to the

damage of the State and the Company of Stationers also; and this will many ways

be evidenced.

Their reasons recall the oscillation theory of modern

specialists in the mysteries of perfect competition. Over-production would result from an

absence of copyright:

For first, if it be lawful for all men to print all

copies, at the same time several men will either enviously or ignorantly print

the same thing, and so perhaps undo one another, and bring in a great waste of

the commodities…

and under-production also:

Secondly, the fear of this confusion will hinder many

men from printing at all, to the great obstruction of learning, and suppression

of many excellent and worthy pieces.

Booksellers’ risks and costs would

increase:

Thirdly, Confusion or Community of Copies destroys that

Commerce amongst stationers, whereby by way of Barter and Exchange they furnish

books without money one to another, and are enabled thereby to print with less

hazard, and to sell to other men for less profit.

177

Even professional authors come in for

consideration:

Fourthly, Community as it discourages stationers, so it

is a great discouragement to the authors of books also; many men’s

studies carry no other profit or recompense with them, but the benefit of their

copies; and if this be taken away, many pieces of great worth and excellence

will be strangled in the womb, or never conceived at all for the

future.

Copyright should pass to heirs and assigns without

term:

Fifthly... many families have now their livelihoods by

assignment of copies ... and there is no reason apparent why the production of

the brain should not be as assignable ... as the right of any goods or chattels

whatsoever.

And finally, in view of the

foregoing:

‘Tis obvious to all, that (if we will establish a just

regulation) foreign books must be subjected to examination, as well as our own,

and that all such importation of foreign books ought to be restrained as tends

to the disadvantage of our native stationers.

The case for copyright has rarely been stated as

comprehensively as in this early petition. Parliament responded promptly with the

requisite Ordinance of 1643 (virtually a re-enactment of an old Star Chamber

decree), to which we owe at least the inspiration of John Milton’s

Areopagitica of the following year. Under the Commonwealth, political

censorship was continued, and after the Restoration the office of Licenser was

revived by an Act of 1662 (13 and 14 Car. II, C. 33) which was

little more than a new version of the former ordinances. The Act expired in 1679, was renewed in

1685, continued again till 1692, and then re-enacted for two more years. It lapsed finally in 1694. Until then, the control of the

Stationers’ Company continued over all copyright, which had to be registered in

its books; but thereafter its authority to restrain reprinting

ceased.

6. Competition, and the first Copyright

Statute

As we have seen, authors could expect little benefit to

themselves from the patent system. The printer who enjoyed the patent right

for a particular class of book had a buying monopoly for all manuscript books in

that class, and authors were in his hands. Under the control of the Stationers’

Company, as members began to compete among themselves for the right to issue new

books, authors were gradually enabled to bargain with more success. In the seventeenth

178

century some of them were in a position to sell the

rights to publish only one edition of a stated number of copies; and cash

payments, in addition to the delivery of the authors’ copies, became more

general. The bulk of the publishing

business came into the hands of the

7. The “perpetual copyright”

question

In view of the claims which the Stationers’ Company had

hitherto made, the terms of the Copyright Act of 1709-10 are significant.

In the case of existing books, the

Act gave the authors, or if they had transferred their rights (which, of course,

they almost invariably had) the then proprietors, the sole right of printing

them for twenty-one years and no longer. In the case of new books, the author was

given the sole right of printing them for fourteen years from the date of

publication, and, if then still living, for one further term of fourteen years.

The penalty for pirating was

forfeiture and a fine of one penny per sheet, the protection extending only to

books registered at the Stationers’ Company. It will be noticed how closely the Act

followed the patent system for inventions, as preserved in the Statute of

Monopolies of 1623. The London

booksellers, who must by then have despaired of ever securing the perpetual

copyright which at one time they had claimed, had no reason to oppose the grant,

enforceable in the Courts, of

180

fourteen years of monopoly power for every new book they

bought outright, although some of them subsequently protested when they realised

that the second period of fourteen years granted to authors who were still

living was the author’s property to sell again. [1]

Authors themselves were placed in a much better

bargaining position. Their success

depended upon individual popularity and reputation. As regards “bargaining power,” they

needed only to avoid committing themselves far ahead in any one contract, for if

their books sold well they could rely on booksellers to bid up each other. The career of David Hume as an author

well illustrates the position. [2] In 1739 at the age of twenty-eight he

sold the rights to the first edition in two volumes of his first book, A

Treatise of Human Nature, 1,000 copies to be printed, to John Noon,

bookseller, for fifty guineas and twelve bound copies. A year later, the third volume, A

Discourse Concerning Morals, was ready, and although

1. For an entertaining and informative account of

this period see Augustine Birrell: Seven Lectures on the Law and History of

Copyright in Books. (Cassell, 1899.)

2. See The Letters of David Hume, edited by

J. Y. T. Greig.

3. Letter,

And again, letter,

180

“from the beginning to the accession of Henry VII,” for

₤1,400, “the first previous agreement ever I made with a

bookseller.” Millar apparently also

bought the “full property” in the first two volumes of the History for

another eight hundred guineas. Nevertheless, David Hume had reason to

protest frequently against the sharp practices of Andrew Millar, who deceived

him continually concerning the size of editions and their rate of sale, and

reprinted an edition without giving the author the agreed opportunity to correct

the text.

Andrew Millar took a leading part in the renewed attempt

which the

1. The three famous cases of Tonson v. Collins,

1760; Millar v.

181

eleven for Becket. [1] “Thus for ever,” says Birrell,

“perished perpetual copyright in this realm.” The

This rapid survey of the early history of copyright in

this country will have served its purpose if it makes more clear the interests

concerned in the important changes introduced into the law by the Act of 1842 (5

and 6 Vic., c. 45), which remained in force right through the remainder of the

nineteenth century and was only superseded by the present Copyright Act of 1911.

The Copyright Act of 1842 had the

effect in general of adding another fourteen years to the monopoly period. Copyright was made to extend for the life

of the author plus seven years, or forty-two years from the date of publication,

whichever period was the greater. There may be doubt whether the volume of

authorship was thereby increased, but it certainly increased the profits to be

made from the sale of successful books. The immediate occasion for the passing of

this important measure is of interest; if the evidence of a publisher of the

time is to be accepted, [2] the Bill

found favour in the House of Commons “because it was understood to be for the

special benefit of the family of Sir Walter Scott, whose copyright was about to

expire under the old law.” More

specific and less far-reaching means of achieving that particular end might well

have been devised.

1. It is of interest to note that David Hume at

once wrote to Wm. Strahan, the successor to Millar’s business, suggesting the

transference afresh to him of Hume’s property in his most recent alterations to

his works. “If nobody can reprint

these passages during fourteen years after the first publication, it would

effectually secure you so long from any pirated edition.” (Letter,

2. Cf. Evidence of John Henry Parker, a retired

publisher, before the Royal Commission on Copyright of

1876-8.

182

For seventy years the Copyright Act of 1842

exercised a far-reaching influence on the output and prices of English books

in the

The defence of high prices in

1. Cf. Evidence of R. A. Macfie, before the same

Commission, and see also A.-C. Renouard: Traite des Droits d’Auteurs,

2. Edinburgh Review, October 1878; article on the

Report and Evidence of the Royal Commission on Copyright. Cf. also The Humble Remonstrance of the

Company of Stationers,

183

device for securing in this way the diversion of scarce

resources to particular uses. It is

involved in the patent system for inventions, in the chartered-company method of

opening up “new” territories, in the “public utility corporation” for the

provision of services, and so on. What is generally overlooked by the more

enthusiastic advocates of these schemes is the alternative output which the

resources would have yielded in other employment. T. H. Farrer, giving evidence before the

1876-8 Commission, no doubt had these considerations more or less clearly in his

mind when discussing the weaknesses of copyright. “What we want, I believe, is more good

books and cheaper good books; but we do not want more books; we have too many

books at present. Some persons,

whose opinions are deserving of much consideration, wish to do away with

copyright in order to diminish the number of books, and to reduce the number of

those who make authorship a trade. They think that to do so would be a gain

to the public in providing better books, and that it would not discourage those

who write for the sake of reputation or for the sake of truth, and less for the

sake of money. I do not say that I

agree with these persons, but I think they are right in thinking that we have,

under the present system, too many books.” [1

The fact is, of course, that the eminent publishers who

have called attention to the inevitable element of risk in the conduct of their

affairs have been prone to exaggerate the unreliability of their judgment in

selecting manuscripts for publication at their own risk. Suppose it to be true that four books out

of five fail to pay: are they all - were they ever all - issued at the

risk of the publisher? Faced with

really risky propositions, do they not suggest to the luckless author that he

should share the risk with them, or bear the whole costs, or secure a subsidy

from elsewhere? Would it indeed be

sound business for a publisher to subsidise definitely hazardous enterprises out

of the monopoly profits gained through copyright? Insurance companies select the risks they

bear, and publishers do likewise, notwithstanding the fact that the funds

they risk arise in part from monopoly profits. Where guess-work is a fair description of

the publishing business, copyright no doubt increases the amount of risk-bearing

by lengthening the odds receivable on the winners. It fails, however, to describe a great

part of the book-publishing trade. The fortunes of

1. Evidence of T. H. Farrer, the Secrtary to the Board of

Trade,

184

publishers vary enormously, but the differences are not

by any means attributable to luck alone. The authors who (it is of interest to

observe) were included on the 1876-8 Royal Commission had had experience with

publishers of widely varying success. To Dr. Wm. Smith, for instance, “only one

book in four is a very moderate calculation of the books which are successful,

of the books which pay their expenses.” Anthony Trollope on the other hand had

“learned from two publishers within a short period that not one book in nine has

paid its expenses, and that still they have been able to carry on the trade.”

The comment of the Secretary to the

Board of Trade was that “the public and the successful author must have to pay

handsomely for the publishers’ unsuccessful speculations.” [1] To the extent that

publishers are successful in selecting books which sell, for issue at their own

risk, and in requiring the authors to finance the publication of the remainder,

copyright legislation does not have the effect of inducing them to undertake

more risk-bearing. If the intention

be to secure the publication of books for which in a free market authors would

have to pay, more certain methods of achieving that end could certainly be

devised. And if it could be assumed

that there are public reasons for subsidising the production of such books,

students of public finance will probably agree that more equitable means could

be found of distributing the cost. It is not, however, to be expected that

many people would support

the principle of indiscriminate encouragement of all books which publishers

regard as unlikely to sell in sufficient volume to cover their cost. And this is precisely the result which

copyright may secure.

10.

The fixing of prices: author v.

publisher

It may be useful at this stage to set out the interests

of authors and publishers respectively in the prices to be charged for books

under copyright monopoly. It is not

to be supposed that both parties are necessarily best served by a price which

restricts the supply of a book to the point of maximum net profit to the

publisher. The author’s interest

will depend rather on the terms of his contract with the publisher, and

generally he will be better served by a larger edition and lower selling price

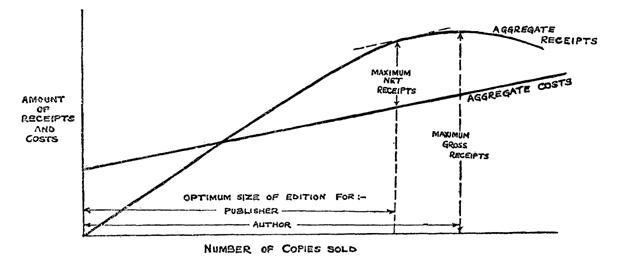

than will pay the publisher best. Where the publisher is the entrepreneur,

he is concerned to maximise the surplus of aggregate receipts over aggregate

costs. The

1.Evidence,

185

author on the other hand, if paid a fixed sum per copy

or a percentage of the published price, has no concern with costs. If paid a fixed sum per copy, the

author’s receipts will be greater, the lower the final price and the greater the

number of copies sold; if he receives a percentage of the published price, his

receipts will be greatest when the gross receipts from sales are

maximised, not (like the publisher) when net receipts after deduction of

costs are greatest. Since every

additional copy printed adds something to the aggregate costs of an

edition, net receipts and the publisher’s profit are maximised at a

smaller output and higher price than would result in the greatest gross

receipts and author’s income. The divergence of interest is shown

clearly in a diagram exhibiting aggregate receipt and cost

curves.

The author is therefore usually interested in securing a

price and output nearer to the competitive figures than those which pay the

publisher best. Only when the

author becomes a joint entrepreneur, and shares the net profits with the

publisher after the deduction of costs, do their interests in monopoly

restriction coincide; and only in the case in which the author takes the whole

risk and pays the publisher a commission based on costs or gross receipts is the

author concerned to issue a smaller edition at a higher price than the publisher

would wish for.

11.

Price discrimination at home and

abroad

In the nineteenth century the extremely high prices

which English publishers exacted for books, behind the copyright law, led to the

emergence of the circulating libraries, which became in due course a powerful

vested interest standing in the way of a lower-price policy. As the most

important

187

buyers of new books, particularly novels and biography,

and dependent upon high book prices for public support, the circulating

libraries attained to a position in which they could insist upon the publishers

maintaining high prices to the public for a term of years while supplying the

libraries at less than wholesale rates. [1] By issuing first an expensive and later a

cheaper edition, the publishers practised a very profitable form of price

discrimination in the home market; but the libraries enforced a longer delay

than some of them desired.

A discriminating price policy for the overseas markets

has long been a regular feature of the publishing trade. Circulating libraries may pay less than

booksellers for their supplies, but “colonial editions “ usually sell at still

lower prices. In the nineteenth

century the reasons were diverse: the colonial communities were poorer, less

interested in books and more cheaply supplied from other countries, particularly

the

12.

The “compulsory licence” or “royalty”

proposal

In such circumstances it is not surprising that

increasing attention came to be paid to proposals for encouraging competition

between English publishers by the introduction of the compulsory licence or

“royalty” system. As has been said,

the Keeper of Printed Books at the

1. See evidence to the 1876-8 Commission, e.g. George

Routledge: “... In the case of

novels published for the circulating libraries, you must give the trade a

certain time [before lowering the price], or else they will not take them.”

Sir Charles E. Trevelyan: “… No

doubt if the monopoly were abolished the circulating libraries would

collapse.”

187

assigns. Thereby the supply of successful books,

and quite possibly the remuneration of authors, would be increased. In

1. Evidence of T. H. Farrer on January 3 1st, 1877: “It is, however, at the present

moment in this country, scarcely a practical question… Whatever advantages a

system of royalty might have, it would require new machinery of an elaborate

kind, and it would disturb existing arrangements, and be opposed by existing

interests. It is, therefore, not

worth while now to discuss it, nor am I prepared to meet the various

difficulties of detail which would no doubt arise in considering it. To do so would require a far greater

knowledge of the practice of the trade than an outsider can pretend to. But judging from the little I have been

able to gather I should not think them insuperable.”

188

of the Commission as “of the graver class which do not

appeal to the popular tastes.” Students of philosophy were fair game for

monopolistic authors.

13.The Copyright Act of 1911:

the

introduction of the “royalty” system

These considerations, therefore, were responsible in

1878 for the decision of the

Commission that “it is not expedient to substitute a right to a royalty defined

by statute, or any other right of a similar kind” for copyright as it then

existed. It is consequently of

particular interest to observe that thirty years later it was largely due to the

pressure of a group of publishers, in another field, for the adoption of

the royalty or compulsory licence system that the present amending and codifying

Copyright Act of 1911

(1 and 2 Geo. V, ch. 46) was framed and passed. The publications in question were

mechanical reproductions of musical compositions. In 1908 a revised International

Copyright Convention was signed in

189

insisting on their right “to control the mode in which

their pieces are produced and the character of the instrument which produces

them.” The Committee with one

dissentient reported in favour of the thirteenth article and the composers, and

against the compulsory licence system. Nevertheless, the 1911 Copyright Act (Section

19) made provision for

compulsory licences for “records, perforated rolls, or other contrivances by

means of which … [musical works] may be mechanically

performed.”

The method adopted in this country for remunerating the

composer differs from that in the United States, where a fixed specific royalty

of two cents was made payable on each gramophone record. The gramophone companies favoured the

American system, and in their evidence before the departmental committee they

opposed a royalty system based on a percentage of the selling price of the

record, on the ground that a composer would then be “paid for the value put into

it by the interpretation of the great artiste.” There was further the problem of deciding

one rate of remuneration for all composers. Both difficulties had been anticipated in

1838 by A.-C. Renouard. [1] The basis adopted in the Act was, after

the first two years of its operation, 5 per cent, royalty on the retail selling

price of the contrivance, with a minimum of one half-penny for each separate

musical work in which copyright subsists. The Board of Trade is empowered, after

public inquiry, to vary the rate by provisional order, at minimum intervals of

fourteen years; and the administration of the system is controlled by the Board

by regulation, apparently without insuperable difficulty.

The Act of 1911 again increased the

duration of copyright in general, but in the same clause a most important

innovation was inserted, at last introducing the royalty system into book

publishing for the last twenty-five years of the copyright period. During that time, any person may

reproduce a published work,

1. See his Traité des Droits d’Auteurs, Volume I,

§IX, p. 463. Of the royalty system,

he wrote “Ce qui le rend inadmissible, c’est l’impossibilité d’une fixation

régulière, et l’excessive difficulté de la perception. Peut-être, a force de soins,

surmonterait-on les obstacles a

la perception; mais, quant a la fixation de la redevance,

le réglement en est impossible… Demandera-t-on a la loi de determiner une

redevance fixe? mais quoi de plus injuste qu’une mesure fixe, rendue commune

a des objets

essentiellement inégaux? … Si votre redevance a pour base une

valeur proportionnelle, chaque Télémaque de deux cents francs produira, pour le

seul droit de copie, plus que ne vaudra, dans l’autre edition [a vingt sous], chaque

exemplaire tout fabriqué; et cependant ce sera toujours le même texte qui n’aura

pas plus de valeur intrinséque dans un

cas que dans l’autre.”

190

after giving written notice and on paying royalties of

10 per cent, of the published

price to the owner of the copyright on all copies sold. No great difficulty seems to have arisen

in administering this clause. The

increase in the term of copyright, in accordance with the Berlin convention, to

the life of the author and a further period of fifty years is hardly likely to have

affected the terms of original publishing contracts and the output of authors’

manuscripts; but the new royalty system now makes it possible for at any rate

the second generation of readers after the death of an author to enjoy a wider

circulation of his books at lower prices, in spite of the increase in the

copyright period.

14.

Some

conclusions concerning the necessity for copyright

The conclusions concerning the necessity for copyright

which emerge from this survey may now be summarised. The parallelism with the case of patents

for inventions is of course very marked. In the first place, expectation of direct

reward explains only a part of the total output of literature, just as it fails

to account for more than part of the inventions which are made. Secondly, just as professional inventors

continue to be paid for their services in fields in which the patent system does

not apply, so also have professional authors in modern times been remunerated

for their writings, whether by payment of a lump sum or by way of royalty on the

sale of copies, in a country in which they were unprotected by copyright law.

The publishers of new books are

simply a special case of the manufacturers who exploit new but non-patentable

inventions for which they pay the inventor. (Where no payments have to be made to

authors, and the demand for the book is not in serious doubt, publishers are not

of course deterred by fear of competition from issuing an edition. Of that fact the abundance of

contemporary editions of standard works selling successfully against each other

at different prices and in a variety of formats, affords a continual

demonstration.) Thirdly, copyright

monopoly, like patent monopoly, enables the privileged producers to increase

their receipts from successful products by restricting the supply, and in so far

as experience and special skill are unavailing when a publisher tries to gauge

the relative chances of success of certain kinds of manuscript books, copyright

will, as we have seen, lead to an increased volume of risk-bearing. This consideration applies,

however,

191

over a definitely limited range of books; and it is

extremely doubtful on reflection whether there exist any public reasons for the

indiscriminate encouragement of the literature that falls into this

category. Nor is there any reason

why the increased volume of risk-bearing which copyright may elicit from certain

publishers should materialise in the form of books alone: a prudent business man

might well spread the risk more widely to include some racing or a gamble at

Lloyd’s with his book publishing. The odds might be still more attractive.

It is at least doubtful whether

book-buyers and successful authors should be specially selected, by the effects

of copyright on the price of the books which sell, to provide the fund which

increases the element of gambling inherent in the book-publishing

business.

More authors write books because copyright exists, and a

greater variety of books is published; but there are fewer copies of the books

which people want to read. Whether

successful authors write more books than they otherwise would is a question of

“the elasticity of their demand for income in terms of effort” - they may prefer

now to take more holidays or retire earlier. Some of them are in any case well advised

to write different books - instead of writing what they would otherwise want to

say or have to say, they find it more remunerative to write the sort of thing

for which the demand conditions are most appropriate for ensuring the maximum

monopoly profit.

The expectation of higher profits from book publishing

as the result of copyright tends to increase the number of publishers in the

business. Keen competition between

publishers will enable the authors, whose copyright monopoly they are anxious to

share, to make better bargains; with the result that the remuneration of

publishers will tend to fall to the market rate of return on their capital and

skill in other fields. Apart,

however, from the increased volume of unpleasant “remainders,” the prices of

books will remain above the competitive level so long as copyright

subsists.

There is, of course, no system of economic calculus

which supports the contention that output of the type which monopoly induces is

“preferable” to that which emerges from the different disposition of the same

scarce productive resources resulting from the competitive bidding of the open

market. One special weakness of

copyright monopoly as an administrative device is the non-discriminatory

nature of the encourage-

192

ment it affords to ventures which are too risky to be

embarked upon in a free market. It

is not difficult to imagine particular cases in which literary effort might well

be specially encouraged on public grounds. Large undertakings involving many expert

contributors and expensive illustrations might not invariably find sufficient

backers and “advance subscribers,” in view of the large capital outlay to be

made by the first publishers, to make them commercial propositions. Yet if there were public reasons for

financing particular ventures of this sort, subsidies provided from general

taxation have more to commend them than a copyright monopoly; and if that system

were politically impossible, it would surely be better that copyright monopoly

be limited to such enterprises, by some such system as that in which the

Comptroller of Patents is at present authorised to grant exclusive

licences to manufacturers to exploit inventions which” cannot be … worked

without the expenditure of capital for the raising of which it will be necessary

to rely on the patent monopoly” (Patents and Designs Act, 1907, as amended, Section 27

(s), (c)). It is, however, a far cry from hard cases

of this sort to a comprehensive system of copyright for all new books.

To the economist who studies the

statements of the case for and against the copyright system as we know it, there

is no document more satisfying in its logic than the minority report in which

Sir Louis Mallet, a member of the Royal Commission on Copyright of 1876-8,

stated the arguments against the continuance of the monopoly. His conclusion was that in the absence of

copyright “it will always be in the power of the first publisher of a work so to

control the value, by a skilful adaptation of the supply to the demand, as to

avoid the risk of ruinous competition, and secure ample remuneration both to the

author and himself.” [1

1. The uniformly high quality of reasoning in Sir Louis

Mallet’s minority report can be appreciated only if it is read as a whole, but a

small extract may perhaps be quoted with advantage:

“… Property exists in order to provide against the evils

of natural scarcity. A limitation

of supply by artificial causes, creates scarcity in order to create

property. It is within this latter

class that copyright in published works must be included. Copies of such works may be multiplied

indefinitely, subject to the cost of paper and of printing which alone, but for

copyright, would limit the supply, and any demand, however great, would be

attended not only by no conceivable injury to society, but on the contrary, in

the case of useful works, by the greatest possible advantage… The

case of a book is precisely analogous to that of a house, of a carriage, or of a

piece of cloth, for the design of which a claim to perpetual copyright has

never, I believe, been seriously entertained.”

In 1878, however, the abolition of copyright was to Sir

Louis Mallet “a question of the future.” That is still true. As he observed, “in a matter which

affects so large and valuable a property, and so many vested interests as have

been created under copyright laws, it would be both unjust and inexpedient to

proceed towards such a change as has been foreshadowed, except in the most

gradual and tentative manner.” By a

very simple change in our copyright legislation, the next important step forward

might now be taken. It is

practicable, in that it merely changes the date at which part of the already

existing and tested administrative machinery set up under the Copyright Act of

1911 comes into operation in the case of every copyrighted book; and,

further, in that the price policy already adopted by many publishing houses for

their most successful books already conforms very closely to that which the

simple change would ensure for all books which are reprinted after the first

edition. As long ago as 1771, David

Hume wrote to his publisher William Strahan: “I have heard you frequently say,

that no bookseller would find profit in making an edition which would take more

than three years in selling.” In

1876, John Blackwood told the Copyright Commission: “Every publisher now is

aware from actual experience that in order to reap the full benefit of a book,

he must work it in a very cheap form as well as an expensive one.” In our own day, it is surely the common

practice of publishers to issue a cheap edition of successful books very

promptly after the first expensive issue has served its purpose with the

circulating libraries. If the now

existing compulsory licence or royalty system (Copyright Act, 1911, Section 3) were made to

operate a few years - say five years - after first publication, instead of being

delayed as at present until twenty-five years after the death of the author,

security for publishers against competition would be preserved until their first

editions were either disposed of or “remaindered,” remuneration for authors

would continue on all sales throughout the full copyright period, and the public

would no longer have to wait more than five years for cheap copies of the books

they wish to buy. The first edition

might still be issued by the publisher at the price which best suited his pocket

under conditions of monopoly, but if he wished to retain the whole of the

business the compulsory licence system would then

194

compel him to follow the present practice of many

publishers and reissue his successes before the end of the five-year period at a

price low enough to deter competitors. There is, of course, nothing to prevent

the successful sale, side by side, of a number of editions by various publishers

at different prices and in different formats; and in many cases the author’s

remuneration from his 10 per cent royalty under the compulsory licence system

would be greater than it is at present. There remains the theoretical objection,

which we have already noticed in connection with the existing royalty provision,

to fixing one percentage of royalty for all books and to giving authors a share

in the value added by paper-makers and printers and binders to the more

expensive editions; but their practical significance can hardly be deemed to

outweigh the obvious public advantage to be derived from the change. The most widely read authors would still

secure the greatest royalties from books selling at the same price, and

something can even be said for allowing authors additional remuneration if their

books are capable of sale in expensive as well as cheap editions. The change would, of course, tend to

reduce the volume of risk-taking on purely speculative publications - a

consequence which, it has already been argued, is hardly likely to involve any

considerable impoverishment of our literary heritage. Particular cases might still form the

subject of special provision. The objection might be raised

that academic texts and scientific treatises, which undergo constant revision

for each edition, might then be reissued in obsolete condition; but with the

adoption of the system, authors would surely see the wisdom of permitting the

necessary alterations to be made to keep reprinted editions up to date. Drastic modifications would no doubt be

made to an increased extent in the form of entirely new works - a development

which indeed from other points of view has much to commend it. There cannot be any question that it

would be in the public interest to ensure low prices for books as early as

possible after the fate of the first edition has revealed that a demand exists

for them; and it is an important feature of the proposed amendment that it

involves no new administrative principle, that it enables the continuance of, if

not indeed an increase in, the remuneration of authors whose books the public

want, and lastly that it simply confirms and extends throughout the

book-publishing business the price policy which successful publishers already

pursue in their own interests.

195

The Competitiveness of Nations in a Global Knowledge-Based Economy