The Competitiveness of Nations in a Global Knowledge-Based Economy

Leonard M. Dudley †

Space, Time, Number:

Harold A. Innis As Evolutionary Theorist

Canadian Journal of Economics,

28 (4a)

Nov. 1995, 754-769.

What causes economic change? Traditionally, economists have answered that

the explanation lies in exogenous shocks to technology, factor stocks, or

preferences. In the last half-decade of

his career, the Canadian economic historian Harold Innis

(1894-1952) proposed an alternative approach - a theory of endogenous change in

communications technology. He argued

that the principal developments in western social history could be explained

by a process of alternation between media biased towards conservation of

information over time and those biased towards transmission over distance. This

paper demonstrates the close parallels between the concepts used by Innis and contemporary theories of social evolution. It

also indicates the importance for future research of his vision of

communications media as the most fundamental of enabling technologies.

† Université de Montréal

Harold A. Innis Memorial

Lecture presented at the Canadian Economics Association meetings, Université du Québec a Montréal,

Montreal, 2 June 1995. The author thanks

Pierre Fortin, Michael Huberman, Bentley MacLeod, and

Francois Vaillancourt for their helpful comments and

encouragement.

754

What do Innocent III (1160-1216)

and William Henry Gates III (1955- ) have in common other than the same roman numeral after their names? At first glance, very little: the first was a

mediaeval pope; the second is chief executive officer of a contemporary

computer software firm. However, there

are striking parallels in their careers. Both dropped out of college as young men and

went on to become the leaders of powerful organizations specialized in information

processing. Both did so by exploiting

new technologies that reduced the cost of storing information for elite groups

within their societies. And the

contributions of both point to serious limitations in neoclassical general

equilibrium theory.

The problem is to interpret

economic change. Traditionally,

economists have explained changes in the price system by exogenous shocks,

either to preferences, to factor endowments, or to technology. Given such a shock, neoclassical theory is

able to predict its consequences for quantities and prices. Yet if examined closely,

most of such shocks turn out to be new ideas, whether new fashions and customs,

new attitudes to working and saving, or new ways of combining production

factors. Unless an economic theory

provides an explanation for how ideas originate, how they are diffused, and how

they are selected, it is incomplete. In

this sense, the neoclassical heritage is unable to cope with the careers of

Innocent III and Bill Gates. [1]

Yet, I shall argue, changes

such as the transformation of mediaeval Europe under popes like Innocent III

and the current profound restructuring of industrial societies at the hands of

software entrepreneurs like Bill Gates are explained, and indeed predicted, in

the writings of the Canadian economic historian Harold A. Innis.

During a remarkable half-decade of

research between 1945 and 1950, Innis found what he

believed to be a recurrent pattern in western social history. He expressed his ideas in such enigmatic, even

oracular, fashion, however, that readers of his own day and since have had

difficulty understanding them. As

Marshall McLuhan later wrote, Innis’s

writing in this period is compressed into a ‘mosaic structure of seemingly

unrelated sentences and aphorisms’ (McLuhan 1964,

vii). Three samples (with italics added)

will suffice to give the flavour of his style. ‘[The introduction of monopolistic elements in

culture] is accompanied by... collapse in the face of technological change

which has taken place in marginal regions’ (1951, 4). ‘The tenacity of the Byzantine empire assumed

the achievement of a balance which recognized the role of space and

time’ (1950, 167). ‘The relative

emphasis on time or space will imply a bias of significance to the

culture in which [a medium of communication] is imbedded’ (1951, 33). ‘Marginal regions,’ ‘balance,’ and ‘bias’: what

does Innis mean? These quotations are taken from three lectures

that Innis gave in 1947 at Laval University, in 1948

at Oxford University, and in 1949 at the

1. Lucas (1988) and Romer (1986, 1990) have

been among the most innovative in addressing the problem of endogenizing

technical change within the neoclassical model, allowing progress to depend on

the stock of accumulated knowledge.

University of Michigan. In each case, Innis’s method was to look for patterns in the historical

flows of names, events, and dates. Although

there were no equations or logical proofs in his writing, he did, I shall

argue, have a theory. To understand Innis’s ideas, however, we must decode the rather special

vocabulary with which he expressed his thoughts. In doing so, we shall compare Innis’s theory with the generalized Darwinian model of

evolution as defined by the American psychologist, Donald T. Campbell (1965,

27). [2] In addition, we shall explore the links

between Innis’s ideas and the essential elements of

recent evolutionary modelling in economics, as set

out by the German economist Ulrich Witt (1991). [3] Finally, we shall examine Innis’s

theory of communications as the key to a new approach for modelling

technological change.

In the late 1940s and

1950s, Harold A. Innis was perhaps Canada’s leading

scholar. He was the author of three

well-received studies on Canadian economic history, A History of the

Canadian Pacific Railway (1923), The Fur Trade in Canada (1930), and

The Cod Fisheries (1940). In each

book, Innis examined how changes in the techniques

for producing primary products - staples - affected patterns of social organization

over long periods of time in regions on the periphery of European civilization.

He was head of the Department of

Political Economy at the University of Toronto and was first dean of the

graduate school of that university. As a

sign of international recognition, he was elected president of the American

Economic Association.

In 1945, immediately

following the Second World War, Innis was invited to

visit the Soviet Union. He was fifty

years old at that time, and the journey marked a turning point in his thinking.

It was a shock for him to witness the

accomplishment of a structure of social organization so completely different

from the market system that he had studied in detail. In a letter, he wrote: ‘I felt the necessity

for a much broader approach in economic history and the very great danger of a

very narrow approach such as we seem to get nothing else but’ (Creighton

1957/1978, 122).

The opportunity to deliver

a more general message to a wider audience came the following year. In May 1946 Innis

was elected president of the Royal Society of Canada, an interdisciplinary

group of leading Canadian researchers. The

position required that he deliver a presidential address the following year. It was about this time that Innis began to put together what we might today call a set

of hypertext files. They were

cross-referenced index cards on which Innis noted his

ideas as they came to him. [4]

2. Durham (1991) reviews the development of Darwinian theories in

anthropology.

3. Robson (1995) applies an evolutionary model to explain

attitudes towards risk in economics; Carmichael and MacLeod (1994) suggest that

social customs may be modelled with biological

models; Paquet (1995) surveys theories of

institutional evolution.

4. These notes were subsequently sorted and published by Christian

(1980).

756

Innis presented a first version of his broader approach to

economic history in May 1947 in Quebec City in a lecture entitled, ‘Minerva’s

owl’ (1951, chap. 1). The theme of his

study was the diffusion of new technologies - how the use of an innovation

spreads over time. This subject had been

discussed in brilliant fashion in the recent writings of Joseph Schumpeter, who

explained cyclical changes in output by the impact of innovations. In Capitalism,

Socialism and Democracy (1942), the Austrian economist had argued that the

principal source of contemporary economic innovation was the large-scale

corporation, which alone had the capacity to coordinate research and the

resources to apply new technologies.

Innis’s ideas were sharply different from those of

Schumpeter. Instead of dealing with new

technologies in production and transportation, Innis

focused on new communications media. Rather

than limit himself to markets for goods and services, he enlarged his scope to

cover the overall pattern of interaction within the society. Instead of concentrating on the monopolistic

structures at the centre, he directed his attention to the competitive fringe,

the contesting forces on the geographic periphery.

The question that Innis asked his Quebec audience was the following. If the dominant group within an organization

derives its power from a monopoly of the existing communications technology,

how can an alternative form of communication with different characteristics

possibly spread? Taking issue with

Schumpeter, he argued that it is not in the interest of the group that holds

power to encourage innovation. Indeed,

he went on, those who hold a monopoly of knowledge will actively resist the

introduction of new techniques. He

quoted Albert Guérard: ‘To the founder of a school,

everything may be forgiven except his school’ (1951, 4). As a result, a new technology can spread only

in marginal regions where the dominant elite’s power is weak. ‘In the regions to which Minerva’s owl takes

flight the success of organized force may permit a new enthusiasm and an

intense flowering of culture incidental to the migration of scholars engaged in

Herculean efforts in a declining civilization to a new area with possibilities

of protection’ (1951, 5).

As in most of his last

works, Innis’s style was that of theme and historical

variations, with very little in the way of recapitulation. After a brief introduction written in this

dense, epigrammatic style, Innis proceeded to a long

series of historical case studies. One

of the most interesting of these examples concerns the spread of parchment,

along with a new script and a standardized written vehicular language, in early

mediaeval Europe. Parchment, a writing

material made from the skins of animals, was discovered about 200 BC. Until the eighth century, however, the

preferred medium for administrative purposes was papyrus, a kind of paper made

from reeds.

Within the Christian

Church, a monastic movement had begun by the fourth century. Under the later Roman emperors and their

Byzantine and Germanic successors, the monasteries remained under centralized

control. Only on the fringes of the

former Roman Empire, in Ireland and subsequently in England, did the monasteries

acquire a certain degree of autonomy. Here

the abbots took the initiative of having existing works from throughout

Christendom transcribed onto parchment.

With the Arab conquest of

much of the Mediterranean basin in the seventh and eighth centuries, supplies

of papyrus to western Europe were cut to a bare

trickle. Since papyrus decomposes within

about three generations, virtually the only knowledge retained was that

transferred to much more durable parchment by monks. The parchment codex manuscripts in the

libraries of English monasteries therefore became a principal repository of

European learning. From England St

Boniface (675-754) was sent out to convert the pagan German tribes,

introducing Latin on parchment into central Europe. Another Anglo-Saxon churchperson, Alcuin (735-804), was the principal adviser to Charlemagne

and the author of reforms that standardized Latin culture across western Europe

(ibid., 14-17). Innis described how

the ‘clear, precise, and simple’ Carolingian minuscule, developed under Alcuin at the court of Charlemagne, gradually spread

throughout western Europe.

In this example, Innis was explaining how a new communications medium,

standardized Latin as a vehicular language in a new script on a new material,

gradually spread from the British Isles throughout northern Europe. In essence, the new idea was carried from

monastery to monastery from the periphery to the centre, successfully

replicating itself in each new host institution.

Is there a more general

process involved? In an essay on

theories of cultural evolution published in 1965, Donald T. Campbell set out

the criteria that a Darwinian model of evolution must satisfy. One of them is ‘a mechanism for the preservation,

duplication, or propagation of... variants’ (1965, 27). Innis’s concept of

the margin, by which a new communications technique establishes a foothold in

an isolated region, successfully reproduces itself, and eventually challenges

the dominant medium, would appear to satisfy this criterion. Indeed, the suggested mechanism is quite

similar to that proposed by biologists to explain the emergence of new species

(see, e.g., Dawkins 1986).

Why should Innis’s approach be of interest to economists? The economic analogue to the biological

concept of reproduction is the process of technological diffusion. Witt (1991, 91-6) points out that the basic

principle in evolutionary models of diffusion is what is called the

frequency-dependency effect. Each individual

in a population must decide whether or not to adopt a new technique. The probability that she adopts, however, will

be a function of the number of members of the population who have already

adopted it. In the mediaeval case, monks

travelling slowly from one monastery to another were

the principal means of diffusion. The

greater the number of monasteries that had already adopted the technology, the

more likely a non-adopter was to receive a visit from converts to the

innovation. In any given sub-population

of monasteries, however, some threshold may have been required before the new

technique was adopted.

In short, in this essay Innis took the first step towards the construction of an

evolutionary model of social change. His

theory was still incomplete, but already Innis had

left his audience of the Royal Society of Canada far behind. His biographer, the historian Donald

Creighton, wrote that his lecture, ‘Minerva’s owl,’ was ‘much too long’ and

that ‘many in his audience were puzzled or bewildered’ (1957, 127).

758

In June 1946, a month after

his election as president of the Royal Society of Canada, Innis

had received an invitation from the administrators of the Beit

Fund of Oxford University. They asked

him to deliver six lectures ‘on any subject in the economic history of the

British Empire,’ undoubtedly expecting him to write on the economic relations

of colonial regions like Canada to the imperial centre in Britain (Creighton

1957, 126). Over the next two years, Innis did indeed prepare six lectures for an international

audience. The context of these lectures

was by no means confined to a single subject, however, nor did he limit his

attention to economic phenomena; most strikingly, his talks had little to do

with the British Empire.

Innis began the Beit Lectures on

12 May 1948 at All Souls College. He

warned his listeners at the outset that a slight digression might be necessary.

‘I shall attempt to outline the

significance of communication in a small number of empires as a means of

understanding its role in a general sense and as a background to an

appreciation of its significance to the British Empire.’ Six lectures, later, this slight digression to

look at a small number of empires turned out to have been a new theory of

historical change.

We have seen that the first

of Innis’s concepts, the margin, proposed a process

of technological diffusion. The question

that he now addressed was whether or not this process attained an equilibrium and if so, whether two or more technologies

would coexist in such a state. [5] For each communications medium, Innis

asserted, there will be a corresponding form of social organization. Some media will favour

decentralization, while others will favour centralization.

Balance is reached when the centrifugal

forces of the former are exactly offset by the centripetal forces of the

latter. ‘Large-scale political

organizations such as empires... have tended to flourish under conditions in

which civilization reflects the influence of more than one medium’ (1950, 7). It is in such a situation, Innis

felt, that social welfare will be highest. We have seen that he noted approvingly the

balance between what he referred to as time and space in the Byzantine Empire.

A more likely outcome was

for one medium to dominate the others. Such a monopoly situation would then lead to

rigidity and decay. ‘We can perhaps

assume that the use of a medium of communication over a long period will

eventually create a civilization in which life and flexibility will become

exceedingly difficult to maintain’ (ibid., 34).

It was such failure to

achieve balance, Innis argued, that led to the

political instability characteristic of the west in pre-modern times. Innis devoted an

entire lecture in his Oxford series to mediaeval Europe. Under the papyrus and stylus medium of the

Roman Empire at its height, Europe was administered from a central point. But under the parchment and pen medium that

succeeded it, power was decentralized. The

hierarchic structures of empire were replaced by networks

5. In terms of evolutionary theory, does the process of replication lead

to an evolutionarily stable equilibrium in which mutant replicators

are eliminated? If so, is that

equilibrium polymorphic, that is, characterized by more than one replicator? See Binmore (1992, 422-9).

of monasteries and their secular overlords. ‘In contrast with papyrus, which was produced

in a restricted area under centralized control to meet the demands of a centralized

bureaucratic administration and which was largely limited by its fragile

character to water navigation, parchment was the product of a widely scattered

agricultural economy suited to the demands of a decentralized administration

and to land transportation’ (ibid., 140).

In western

Europe, a brief period of balance between the state with its tendency towards

centralization and religion with its generally decentralized structure was

achieved during the Carolingian renaissance from 768-814. After Charlemagne’s reign, however, the empire

of the Franks broke up into competing states, the basis of the modern nations

of Europe. By the thirteenth century the

papacy under leaders like Innocent III had managed to impose its authority over

the secular rulers of these successor states, including Frederick II, the Holy

Roman Emperor. ‘A civilization dominated

by parchment as a medium developed its monopoly of knowledge through

monasticism. The power of the Church was

reflected in its success in the struggle with Frederick II’ (ibid.,

165).

What is the process by

which one medium and its associated form of social organization are replaced by

another medium and an alternative social structure? For Innis, one

mechanism was competition for territory between states. For example, even though it was much smaller

in territory than the Roman Empire, the kingdom of Charlemagne was too large to

survive external predation. ‘Attacks

from the Danes and the Magyars accentuated local organizations of force and

separatist tendencies’ (ibid., 149). A second mechanism was competition between

centre and periphery for popular support within a given society. ‘ The monopoly of knowledge which had been built up invited

competition from a new medium of communication which appeared on the fringes of

western European culture and was available to meet the demands of lower strata

of society’ (ibid.).

In short, a system that is

more successful than another in feeding and protecting the majority of its

adherents will tend to be selected. This

process by which competition between systems results in retention of one way of

life and elimination of the other in Innis’s theory

therefore satisfies the second of the requirements set out by Campbell for a

Darwinian model of evolution; namely, ‘consistent selection criteria’ (1965,

27). A struggle for survival among

states and among groups within states weeds out less successful forms of

organization.

Innis’s idea of balance should be distinguished from the

concept of equilibrium in neoclassical economic theory. As Witt (1991, 96-8) has remarked,

neoclassical general equilibrium theory takes a strong position on the issue of

social coordination, proposing that an economic system converges to a state of

perfect coordination - equilibrium. All

firms in an industry, for example, will use the identical production

technology. For an evolutionary

approach, it is necessary to introduce the de-coordinating force of innovative

activity. To survive, agents must keep

within the moving bounds set by coordinating forces of markets and the

de-coordinating forces of innovation.

By these standards, Innis’s theory is clearly evolutionary. At any moment in a given society, different

communications technologies are likely to coexist. Indeed,

760

his ideal is a state of balance in which two or more

media of communication are used. Such a

state of balance is likely to be temporary, Innis

realizes, since one technology will tend eventually to dominate the other. Even then, however, there is no enduring

equilibrium, since, as we have seen, the monopoly position of the dominant

technology induces de-coordinating innovative activity.

Once again, Innis had raced far ahead of his audience. The reception of the six Oxford lectures also

was disappointing. ‘Innis’s most comprehensive and original thesis was

presented prematurely, too briefly and without the [necessary] vast mass of

supporting evidence and illustrative material’ (Creighton 1957, 135). Yet he had accomplished the essential. In his two years of research, Innis had acquired a mastery of the historical details of

social change. He could now add the

third and crucial element to his theory.

During the winter of 1948-9,

while Innis was finishing the revisions to his Oxford

lectures, to be published as Empire and Communications (1950), he

received an invitation to participate in a Royal Commission on Transportation

headed by W.F. Turgeon. The gruelling task

would consume much of his energy over the following two years. But before becoming involved in the

preparations for the Commission’s hearings, Innis

took the time to prepare an essay, ‘The bias of communications,’ which he

delivered at the University of Michigan in April 1949. The result was a synthesis of the two previous

studies and his most complete explanation of the process of historical change.

Perhaps the most difficult

of all problems in economic theory is to explain how new ideas arise. To deal with this problem, Innis

used the concept of bias. [6] Here Innis was dealing with the direction

of technical change. He was not, as

one might expect, referring to whether capital or labour

is saved, but rather to whether an innovation is designed to allow knowledge to

be transmitted more efficiently over space or to be preserved more effectively

over time. ‘According to its

characteristics [a medium of communication] may be better suited to the

dissemination of knowledge over time than over space, particularly if the

medium is heavy and durable and not suited to transportation, or to the

dissemination of knowledge over space than over time, particularly if the

medium is light and easily transported’ (1951, 33). Innis suggested that

both the direction and the rate of change are endogenously determined. ‘Monopolies or oligopolies of knowledge have

been built up in relation to the demands of force chiefly on the defensive, but

improved technology has strengthened the position of force on the offensive and

compelled realignments favouring the vernacular’

(ibid., 32). In other words, the elite

group that dominates the old technology will receive a monopoly rent from its

position. However, the high price for

information will encourage the development

6. Innis also used the notion of bias in the

introduction to Empire and Communications (1950, 7). The idea that the bias of

the dominant medium leads to innovation to correct the bias, however, is expressed

most clearly and consistently in the 1949 paper (1951, 34, 38, 40, 48, 49, 50,

60).

of a new technology with different characteristics,

intended to lower the cost of knowledge to the rest of the society.

An example from the

mediaeval period illustrates this concept of bias and its significance. The communications medium of the Roman Empire,

light but perishable papyrus, encouraged an excessive concern for territory;

that is, space. In the eighth century

the Arab conquest of the south shore of the Mediterranean Sea drove up the

price of papyrus to western Europe. The Carolingian monks were therefore forced to

turn to an alternative medium, parchment, which was heavier but much more

durable. Combining parchment with a new

standardized script, the Carolingian minuscule, they developed a powerful new

communications medium. As a result, over

the following centuries the previous bias towards extension over space was

replaced by a bias towards duration over time. The military-administrative bureaucracies of

the Roman Empire and its successor states were replaced by the religious bureaucracies

of the high middle ages (ibid., 48-50).

In proposing a process of

directed endogenous technological change, Innis was

taking a position sharply at variance with neoclassical economics, which has

considered technology to be exogenous. However,

he was offering the final component of an entirely different approach to social

organization. The third of Campbell’s

criteria for a Darwinian model of evolution is the ‘occurrence of variations’

(1965, 27). Innis’s

concept of bias, by which monopoly pricing generates new technology with

characteristics different from the old, clearly fits this requirement.

Innis went beyond the Darwinian model. The mutations in technology he described are

not the results of a random process. Rather, they are a reaction to price data. Innovations seem to be generated by what Witt

(1991, 89) calls a ‘satisficing’ mechanism in which

action arises from dissatisfaction with the current outcome. If so, Innis was

going beyond the evolutionary theory of his contemporary, Schumpeter, who had

little to say about how new ideas arise (Freeman 1990, 22). He was proposing the key element of a theory

of social change, namely, a model of cultural evolution.

There is no indication in

Creighton’s biography of how his American audience reacted to this

presentation. Together with Innis’s 1947 Royal Society address and several other

essays, the Michigan lecture was published in 1951 as a book,

The Bias of

Communication.

V. A Bumper-Car Theory of History

A popular ride in amusement

parks of the early postwar decades was the electric bumper car. By pressing on a pedal, the rider caused the

car to move at a fixed velocity until it hit an obstacle - either the bumper of

another car or the barrier around the concession. The vehicle then changed direction until it

hit some other obstacle. Innis’s theory of social change somewhat resembles this

amusement. The position of the vehicle

represents the nature of communications technology. As for the car, it represents social

institutions, and the rider, the population of the society, each carried along

by the momentum of technological change.

The bumpers are

762

the limits to the price of storing information over time

as opposed to the price of transmitting it over distance. At these limits there is a redirection of

society’s resources to search for an alternative communications medium.

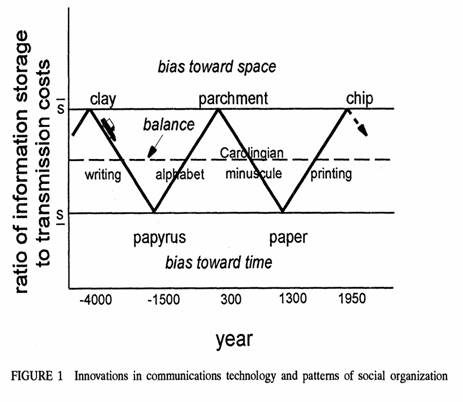

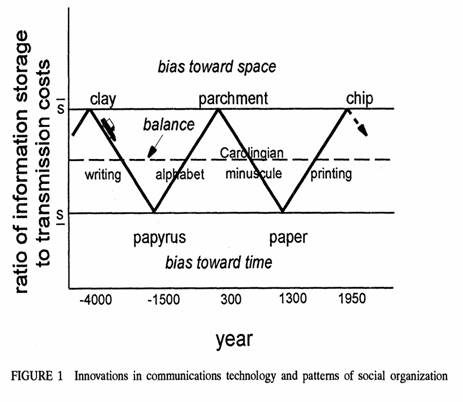

Innis’s theory of history, as told in condensed form in his essay, ‘The bias of communication’ (1951, 33-60), may be illustrated with the help of figure 1.

Here, the ratio of the cost

of information storage to the cost of information transmission is measured on

the vertical axis, while the year is measured on the horizontal axis. In the prehistoric period, as information

accumulated with a fixed memory capacity for each individual, the marginal cost

of storing a unit of information reached the upper limit. In Mesopotamia, a way was found of storing

information by means of pictograms on clay tablets. Subsequently, phonetic writing developed,

using the same materials. The first

civilizations, ruled by a priestly caste, were concerned with time.

The information monopoly of

the ruling elites encouraged the search for alternative media. With the development of papyrus, it became

possible to send information efficiently over long distances. The cost of transmission was further reduced

when the west-Semitic peoples developed a consonantal alphabet capable of

representing human speech with two dozen characters. Using certain of these symbols for vowels, the

Greeks and Romans developed complete alphabets and came to dominate all of the

lands in the Mediterranean basin. Secular

rulers with codes of written law now emphasized the control of space.

Since papyrus crumbled

after three generations, it was not suitable for conserving information over

long periods. In the early Christian

era, the development of durable parchment, which could be bound into easily

consultable books provided

an alternative means of communication. When Arab conquests caused the price of

papyrus to rise in the seventh and eighth centuries, western

Europe switched to parchment and developed a standardized efficient Latin script.

European society of the middle ages was dominated by a religious elite, literate in

this vehicular medium and concerned with the preservation of knowledge over

time.

From the fourteenth century

on, the high cost of sending information over space encouraged the European

production of paper, an invention borrowed from the Chinese. Once again, a lighter, perishable medium was

being substituted for a heavier, durable one. In the fifteenth century the high price of

hand-copied manuscripts provided an incentive to experiment with mechanical

methods of reproducing information. The

resulting fall in transmission costs led to the development of written forms of

vernacular languages and intense competition for territory. In the nineteenth century the invention of

newsprint and steam and electric presses further marked the transition to media

adapted to the control of space. In the

twentieth century radio continued this trend towards an obsession with the

present.

We are now nearing the

moment when Innis’s career itself came to an end. What might he have predicted for the remainder

of the twentieth century? Applying the

model of figure 1, he might well have suspected that after some seven centuries

of preoccupation with space, the bumper car should hit the upper limit of the

ratio of storage of transmission costs. Accordingly,

innovation to reduce storage costs would be induced. The consequence would be a new concern for

time and difficulties with any existing institutions committed to the control

of space.

Applying this reasoning, Innis might have predicted fiscal problems for existing

territorial states. Difficulty in

maintaining cohesion might be particularly severe for states like the Soviet

Union, which had hitherto neglected the time dimension or for states like

Yugoslavia and Canada in which relatively homogeneous regions had different

concepts of time. In addition, Innis might have foreseen additional strength for movements

within individual societies devoted to furthering moral values. This is exactly the pattern that has been

observed in the industrialized world since the introduction of a powerful new

device for storing information, the integrated circuit, a

decade after Innis’s death. [7] Bill Gates is one of those who have recognized its

revolutionary implications. It is the

same pattern found in the history of mediaeval Europe after the death of

Charlemagne. Indeed to foresee where we

might be headed, we might do well to study the career of Innocent III, who was

not even an ordained priest when elected pope at the age of thirty-seven yet

went on to reshape European society.

VI.

The Missing Dimension: Number

It might be argued that it

is absurd to attempt to fit all of western social history within a simple,

two-dimensional view of communications technology as agent of social change. Indeed, the strongest arguments against the

time-space bumper-car

7. For more on this new technology and its effects on patterns of social

organization, see Dudley (1991, chap. 8).

764

model of the preceding section were provided by Innis himself. In

the introduction to one of his last essays, ‘The problem of space,’ he briefly

mentioned an additional concept that he placed on the same level as time and

space, namely, number. ‘Gauss held that

whereas number was a product of the mind, space had a reality outside

the mind whose laws cannot be described a

priori. In the history of thought,

especially of mathematics, Cassirer remarked, “at

times, the concept of space, at other times, the concept of numbers, took

the lead”’(1951, 92; italics added).

Could number be considered

a third dimension to communications technology? If so, how might this concept fit into the

structure that Innis designed to model space and

time? At issue, Innis

realized, is the complexity of the communication system. ‘A complex system of writing becomes the

possession of a special class and tends to support aristocracies. A simple flexible system of writing admits of

adaptation to the vernacular but slowness of adaptation facilitates monopolies

of knowledge and hierarchies’ (ibid., 4). Thus when a complex system of communication is

replaced by a simpler one, there is deeper penetration into the society. What was formerly reserved for

an elite becomes accessible to a much wider segment of the population.

As a result, there is a

change in the nature of social interaction. Innis described two

periods in history when the number of users of a communications medium

increased dramatically. The first change

came with the invention of the alphabet in the eastern Mediterranean in the

second millennium BC. With the

development of a flexible alphabet, the nature of society changed. ‘A flexible alphabet favoured

the growth of trade, development of trading cities of the Phoenicians and the

emergence of smaller nations dependent on distinct languages’ (ibid., 39). Innis noted the divisive effects of the new technology

within the Roman Empire, which towards its end separated into Greek and Latin

components (ibid., 15).

The second period in which

number became crucial occurred subsequent to the development of printing in

standardized vernacular languages in early-modem Europe. ‘By the end of the sixteenth century the

flexibility of the alphabet and printing had contributed to the growth of

diverse vernacular literatures and had provided a basis for divisive

nationalism in Europe’ (ibid.,

55).

In each case, Innis recognized the nature of the change but was unable to

develop the analytical structure required to treat it theoretically. As a result, number became confused with space

in his analysis. It is only after Innis’s death, with the development of the theory of the

public good by Samuelson (1954) and its application to interest-group

activities by Olson (1965), that

the implications of number became apparent. The larger the number of

contributors to the financing of a public good, the lower the price to each.

To the extent that the institutions

required to support a national written language form a public good, the

taxpayers of each nation will therefore have an interest in increasing the

numbers of its citizens.

Indeed, there is an

additional significance to number. Increasing

number not only lowers the costs but also raises the benefits of information

exchange in the vernacular. When a new

member joins such a system of two-way communications, she confers a benefit - a

network externality - to all existing members of the system, since they can now

communicate with an additional user (Katz and Shapiro

1985). Thus number is a crucial characteristic

of certain media of communication. Here,

then, is a task for those who would write the final movements of Innis’s unfinished symphony: the integration of number into

a model of endogenous change in information technology.

Why should change in

information technology command special attention at the expense of more

traditional areas of interest to economists, such as agricultural techniques,

the development of inanimate power sources, or new means of transport? In a word, communications media are arguably

the most fundamental of ‘enabling technologies’ - techniques that allow us to

use other means of production. [8] Rather than simply providing us with more goods and services

from given inputs, innovations in information processing tend to lead us to

interact differently. Recent research on

primate evolution suggests that greater memory, an increased ability to

communicate over distance, and a fall in the cost of reproducing information

through speech each have had a profound impact on patterns of social organization

(see, e.g., Ghiglieri 1989; Leakey and Lewin 1992; Johanson, Johanson, and Edgar 1994). What is new in the historical period analysed by Innis is that these

changes are external to the individual - the result of cultural rather than

biological evolution.

In November 1952 Harold Innis died of cancer at the age of fifty-eight. His fellow economists, W.T. Easterbrook (1960)

and Mel Watkins (1963), along with Marshall McLuhan

(1962), subsequently paid tribute to him in their writings in the early 1960s. Since then, Innis’s

memory has been kept alive by researchers in other disciplines, who recognize

his contributions to the theory of communications, political science, and

geography. [9] Among economists and economic historians, however, he is

rarely cited. [10] Is there something that economists have missed?

As they have grown older,

many of the most active of later twentieth-century economists have quietly

dropped the assumption of rational, optimizing agents learned in their youth. Friedrich Hayek (1973-9), Kenneth Boulding (1973), Jack Hirshleifer

(1980), Richard Nelson (1987), Douglass North (1990), Nathan Rosenberg (1994),

and Richard Lipsey (1995) are among the more

prominent of those who have become dissatisfied with the limits of neoclassical

economic theory. Seeking both a more

satisfactory way of modelling technological change

and a means of broadening the scope of their analysis to cover cultural

phenomena, they have been attracted by the concept of evolution. All of these researchers appear to have been

preceded by Harold A. Innis, although none has cited Innis’s work on communication in his own writings. The basic concepts of Innis’s

theory of

8. For an analysis of this concept, see Lipsey

and Bekar (1995).

9. For a review of research on Innis’s ideas

on media, see Di Norcia

(1990). Christian (1977) portrays Innis as political

scientist, Parker (1988) as geographer. More recently, Innis’s

writings on media have been cited in the discipline of communications by Geiger

and Newhagen (1993) and Deetz

(1994).

10. Neill (1972) and Parker (1988) are exceptions among economists.

766

social change - bias, balance and the margin - are simply

new terms for the Darwinian concepts of mutation, selection, and reproduction. In addition, Innis

pointed to the importance of communications media as the most fundamental of enabling

technologies.

Yet there is a fundamental

objection to this interpretation of Innis’s later

work as evolutionary economics. At no

point did Innis himself draw a parallel between

Darwin’s concept of evolution as ‘descent with modification’ and his own theory

of social change. Innis’s

posthumously published system of filing cards indicates that he was aware of

Darwin’s impact on nineteenth-century social scientists like Herbert Spencer,

who coined the term ‘survival of the fittest’ (Christian 1980, 7, 39). A possible explanation for his own reticence

to employ Darwinist terminology is that in the late 1940s Darwinism in the

social sciences had received an ugly reputation as a result of racist theories

of natural selection advanced to justify Nazi brutality.

Another interpretation of Innis’s silence on this question is also possible. Innis may have

viewed both Darwin and himself as continuing a much older tradition dating back

to the humanism of the sixteenth century. In his essay, ‘A plea for time,’ the third

chapter of his 1951 book, Innis wrote: ‘The linear

concept of time was made effective as a result of humanistic studies in the

Renaissance... It was not until the Enlightenment that the historical world was

conquered and until Herder and romanticism that the primacy of history over

philosophy and science was established... In the hands of Darwin the historical

approach penetrated biology and provided a new dimension of thought for science

(62-3).

Innis, like

Darwin and Marx, was proposing a historical, path-dependent theory of change. In this sense he was very much a follower of

the German idealist philosopher G.W.F. Hegel, for whom history was a dialectic

process by which conflict between opposing forces is resolved. The title of Innis’s

1947 Quebec address is drawn from the preface to Hegel’s The Philosophy of

Right (1952): ‘When

philosophy paints its grey on grey, then has a shape of life grown old. By philosophy’s grey on grey it cannot be

rejuvenated but only understood. The owl of Minerva spreads its wings only with the falling of the

dusk’ (7). Hegel was saying that

it is only in the final phase of a civilization, when decline is irreversible,

that its culture begins to flower. But

Hegel’s statement, written late in his own life, could also apply to a individual thinker like himself - or Harold Innis. Innis’s great synthesis came late in his life when his hair

was streaked with grey. He died

convinced he had found the means of understanding the nature of his own

civilization. But he himself was by that

time powerless to influence the thinking of his contemporaries.

Today, with the technology

to cram much of world’s learning onto an inexpensive disk available to

children, centralized information storage is becoming obsolete. Our increasing focus on the environment,

social justice, and spiritual values may be explained, at least in part, by our

cheaper access as individuals to the information we need to behave consistently

over time. After seven centuries of what

Harold Innis considered an increasing obsession with

space, the west appears to be moving

in the direction of a more balanced society. The moment perhaps has come for Minerva’s owl

to alight on the shoulders of a new generation.

Binmore, K.

(1992) Fun and Games: A Text on Games Theory (Lexington, MA: Heath)

Boulding,

K.E. (1973) The Economy of Love and Fear (Belmont,

CA: Wadsworth)

Campbell, D.T. (1965)

‘Variation and selective retention in sociocultural

evolution.’ In Social Change in

Developing Areas: A Reinterpretation of Evolutionary Theory, ed. H.R.

Barrington, G.I. Blanksten, and R.W. Mack (Cambridge,

MA.: Schenkman)

Carmichael, H.L. and W.B. MacLeod (1994) ‘Gift giving

and the evolution of cooperation.’

Queen’s University and Université de Montréal Working

Paper

Christian, W. (1977) ‘Harold Innis

as political theorist.’ Canadian

Journal of Political Science 10, 21—42

_________ . (1980) The Idea File of

Harold Adams Innis (Toronto: University of

Toronto Press)

Creighton, D. (1951/1978) Harold Adams Innis:

Portrait of a Scholar (Toronto, University of Toronto Press)

Dawkins, R. (1986) The Blind

Watchmaker (New York: Norton)

Deetz, S.A.

(1994) ‘The micro-politics of identity formation in

the workplace: the case of a knowledge intensive firm.’ Human Studies 17, 23-44

Di Norcia, V. (1990) ‘Communications, time and power: an Innisian view.’ Canadian Journal of Political Science 23,

335-57

Dudley, L. (1991) The Word and the

Sword: How Techniques of Information and Violence Have Shaped Our World (Cambridge,

MA: Basil Blackwell)

Durham, W.H. (1991) Coevolution:

Genes, Culture and Human Diversity (Stanford: Stanford University Press)

Easterbrook, W.T. (1960) ‘Problems in the relationship

of communication and economic history.’ Journal of Economic History 20, 134-5

Freeman, C. (1990) ‘Schumpeter’s Business Cycles revisited.’ In Evolving

Technology and Market Structure: Essays in Schumpeterian Economics, ed. A. Heertje and M. Perlman (Ann

Arbor: University of Michigan Press)

Geiger, S., and J. Newhagen (1993) ‘Revealing the black box: information processing and media

effects.’ Journal of Communication 43, 42-50

Ghiglieri, M.P. (1989) ‘Hominid sociobiology

and hominid social evolution.’ In Understanding

Chimpanzees, ed P.G. Heltne

and L.A. Marquardt (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press)

Campbell, D.T. (1965) ‘Variation and selective

retention in sociocultural evolution.’ In Social

Change in Developing Areas: A Reinterpretation of Evolutionary Theory, ed.

H.R. Barrington, G.I. Blanksten, and R.W. Mack

(Cambridge, MA: Schenkinan)

Hayek, F.A. (1973-9) Law, Legislation and Liberty. 3 vols.

(London: Routledge & Kegan

Paul)

Hegel, G.W.F. (1952) The Philosophy

of Right (Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica)

Hirschleifer,

J. (1980) ‘Privacy: Its origin, function and future.’ Journal of Legal

Studies 9, 649-64

Innis, H.A.

(1923) A History of the Canadian Pacific Railway (Toronto: McClelland

and Stewart)

_______ . (1930) The Fur Trade in

Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press)

_______ . (1940) The Cod Fisheries (Toronto:

University of Toronto Press)

_______ . (1950) Empire and

Communications (Oxford: Clarendon)

_______ . (195 1/1964) The Bias of Communication (Toronto:

University of Toronto Press)

768

Johanson,

D., L. Johanson, and B. Edgar (1994) Ancestors: In

Search of Human Origins (New York: Villard)

Katz, M.L., and C. Shapiro (1985) ‘Network

externalities, competition, and compatiblity.’ American Economic Review 75, 424-40

Leakey, R., and R. Lewin (1992) Origins

Reconsidered: In Search of What Makes Us Human (New York: Doubleday)

Lipsey,

R.G., and C. Bekar (1995) ‘Technical change and

economic growth: continuous random shocks vs. occasional paradigm shifts.’ In Technology,

Information and Public Policy, ed. T.J. Courchene

(Kingston, Os: John Deutsch Institute), forthcoming

Lucas, R.E. Jr (1988) ‘On the mechanisms of

economic development.’ Journal of Monetary Economics 22, 3-42

McLuhan, M.

(1962) The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of

Typographic Man (Toronto: University of Toronto Press)

_________ . (1964) ‘Introduction.’ In The

Bias of Communication (Toronto: University of Toronto Press)

Neill, R.F. (1972) A New Theory of Value: The Canadian Economics of

H.A. Innis (Toronto: University of Toronto Press)

Nelson, R.R. (1987) Understanding Technical Change as an Evolutionary

Process (Amsterdam: North-Holland)

North, D.C. (1990) Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic

Performance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Olson, M. (1965) The Logic of Collective

Action (Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press)

Paquet, G. (1995) ‘Institutional evolution

in an information age.’ In Technology,

Information and Public Policy, ed. T.J. Courchene

(Kingston, ON: John Deutsch Institute), forthcoming

Parker, I. (1988) ‘Harold Innis

as a Canadian geographer.’ Canadian

Geographer 32, 63-9

Robson, A.J. (1995) ‘The evolution of strategic behaviour.’

This Journal 28, 17-41

Romer, P.M. (1986) ‘Increasing returns and

long-run growth.’ Journal of

Political Economy 94, 1002-37

_________ . (1990) ‘Endogenous technological change.’

Journal of Political Economy 98, S71— S102

Rosenberg, N. (1994) Exploring the Black Box (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press)

Samuelson, P.A. (1954) ‘The pure theory of public

expenditure.’ Review of

Economics and Statistics 36, 387-9

Schumpeter, J.A. (1942) Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (New

York: Harper)

Watkins, M.H. (1963) ‘A staple theory of economic

growth.’ Canadian Journal of Economics

and Political Science 29, 141-58

Witt, U. (1991) ‘Reflections on the present state of

evolutionary economic theory.’ In Rethinking

Economics, ed. G.M. Hodgson and E. Screpanti (Aldershot, England: Edward Elgar)

769